Image: Shutterstock (author modified)

If this sounds about as responsible as “we should legalize theft of patents at home because patent infringement is rife in China”, then you may well ask where such a nonsensical and counterproductive idea came from. From OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, for one, the same company being sued by the New York Times for copyright infringement for copying and using NYT content without permission to train its AI algorithms.

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, is one of the “tech bro’s” now cozying up to Donald Trump. He is a vocal advocate of allowing the AI industry unfettered access to copyrighted content as part of the AI training process. Last year, in a submission to the UK Parliament OpenAI claimed that it would be “impossible” to train AI without resort to content protected by copyright. Now, it maintains that allowing AI companies to scoop up copyrighted content without authorization or payment is not only “fair use”, a legally unproven proposition that is currently very much a live issue before the courts in the US and elsewhere, but is essential for “national security”. To cite a few choice tidbits from OpenAI’s submission to the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) filed in response to the Office’s request for submissions on the Trump Administration’s AI Action Plan;

“Applying the fair use doctrine to AI is not only a matter of American competitiveness—it’s a matter of national security… If the PRC’s developers have unfettered access to data and American companies are left without fair use access, the race for AI is effectively over… access to more data from the widest possible range of sources will ensure more access to more powerful innovations that deliver even more knowledge.”

And, one could add, more profit for AI companies.

In other words, if the US government doesn’t give AI companies free and unfettered access to whatever content it desires, regardless of whether it is protected by copyright (think curated news content, musical compositions and artistic works, not to mention the published works of countless authors), then China will win the AI race, threatening the national security of the US. Or so Altman’s argument goes.

The AI industry is already a practitioner of the art of helping themselves to OPC (other peoples’ content) without permission, then claiming fair use when they are caught doing it. That is what has led to the multiplicity of lawsuits now before the courts, brought by various authors and content owners. Raising the bogeyman of China and wrapping themselves in the flag by invoking “national security”, is a new wrinkle in the attempts by the tech industry to undermine established copyright law and to wriggle out from under their legal obligations.

“National security” is a convenient catchphrase and pretext in common use today to try to justify and legalize the unjustifiable and the illegal. Donald Trump invoked national security when he used the International Economic Emergency Powers Act (IEEPA) to override USMCA/CUSMA obligations made to Canada and Mexico, treaty obligations that he himself signed in his first term in office. The immediate excuse was the flow of fentanyl across the northern and southern borders of the US. Never mind that the amount of fentanyl seized by US border agents at the Canadian border came to a grand total of less than 43 lbs. for all of 2024, or just 0.2% of the total. (The equivalent for Mexico was 21,148 lbs). National security, and in particular playing the China card, is a political winner these days in Washington.

OpenAI’s position is all the more outrageous because it went into fits when the Chinese startup, DeepSeek, launched its new and much cheaper product, allegedly having used OpenAI’s capabilities to improve its own model. OpenAI cried foul and IP infringement, a case of blatant hypocrisy if there ever was one.

OpenAI and other generative AI companies that have built their training model on permissionless copying are clearly nervous about the possible outcomes of the numerous court challenges to its practices currently underway. Most of these cases are in the US although similar lawsuits have been launched in the UK, Canada, India and Germany. While it is impossible to predict the outcome of specific cases, in a recent decision (Westlaw v Ross), a US court rejected fair use as a defence in the context of AI training data. It did not accept that copying the content was a transformative use, but rather one that created a product that competed in the market with the original source material. Given the legal uncertainties, it looks like the tech industry is trying to hedge its bets by lobbying to have all AI training uses declared to be “fair use” based on national security considerations.

It gets worse than that. Another of the tech bro’s, Mark Zuckerberg, gave the green light to training of META’s AI model on pirated material. This was not accidental. Employees reported removing © marks from books downloaded as training materials.

In Canada, in a similar search for a rationale to explain away copyright infringement, a company that was helping itself to copyright-protected curated legal case data to build an AI based legal reference service, claimed that forcing it to license the content would stifle innovation and drive AI businesses out of the country. See CanLII v CasewayAI: Defendant Trots Out AI Industry’s Misinformation and Scare Tactics (But Don’t Panic, Canada). The AI developers’ strategy seems to be that if you don’t want to license and pay for IP protected content, (or perhaps the owner of the content prefers not to license it, as is their right) just take it and claim some overriding purpose, like protecting domestic innovation or national security.

But what about the argument that if China doesn’t respect intellectual property (IP), we need to adopt the same approach in order to compete? While Chinese courts in recent years have taken a much more robust position with respect to protecting the rights of IP owners, including patents, trademark and copyright, I am not going to argue that suddenly China has become a “rule of law” country. Rather, it is a “rule by law” state, the law being whatever the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) decides it will be at any given moment. This is a fact. However, to suggest that the West, in particular the US, should adopt China’s legal modus operandi so as not to lose the so-called “AI race” not only undermines all the values and principles on which our society is based, including the principles of private property, fairness and transparency, but also dismisses three centuries of legal developments in the protection of IP, especially copyright. The evolution of copyright law has resulted in the creation of industries that contribute far more to the economic and cultural wellbeing of our society than any of the questionable outputs of the AI industry.

Yes, AI is here to stay. It can be put to beneficial or nefarious uses and has an undoubted strategic component. It can also be used to undermine and weaken human creativity. Is that the goal we are seeking?

It is worth noting that the tech bro’s have an easy and legal way out. In most instances, they can acquire access to the content they need legitimately. A market for licensing training data for AI development already exists and is further developing rapidly, as I wrote about earlier. Using Copyrighted Content to Train AI: Can Licensing Bridge the Gap? But just taking it and claiming “fair use” is easier and cheaper. And morally and probably legally wrong.

We have seen a lot of rogue policy making in Washington of late, from the illegal deportation of US residents, to the gutting of US government agencies, to the declaration of a tariff war against the world. It is time to take a more considered approach. Rash decisions in response to tech lobbying could lead to untold consequences and collateral damage to content industries that would be impossible to roll back and remedy. Thus, I was relieved to note that Michael Kratsios, Director of the US Office of Science and Technology Policy, the same OSTP to which OpenAI submitted its comments regarding AI training and national security, stated in a recent speech on American innovation that;

“…promoting America’s technological leadership goes hand in hand with a threefold strategy for protecting that position from foreign rivals. First, we must safeguard U.S. intellectual property and take seriously American research security…”

That is a welcome recognition of the importance of IP as part of the process of innovation.

In this respect, the existing framework of copyright law has survived and adapted for over 300 hundred years. It has evolved with each new technological development, but the fundamental principle of giving an “author” of an original work the right to control how that work is used as well as the ability to earn a return from its use for a statutory period, with only limited exceptions, has remained unchanged. To undermine this principle in a flawed attempt to grasp the Holy Grail of AI leadership is self-defeating. Instead of sipping from AI’s Holy Grail we will be drinking from the poisoned chalice of IP theft.

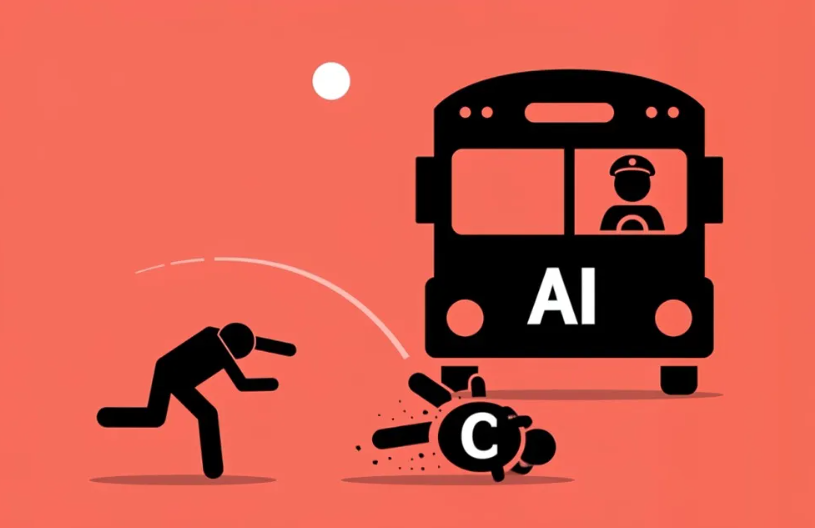

Throwing copyright and the rule of law under the bus on the pretext that this is what’s needed to compete with China is not only self-serving, it is a sure path to ultimately losing the secret sauce of creativity and innovation. A country that steals IP rather than creating and respecting it will always lose the race.

© Hugh Stephens, 2025. All Rights Reserved

This article was originally published on Hugh Stephens Blog