Oppenheimer is a colossal achievement. Christopher Nolan’s film is an exquisitely calibrated epic, brimming with ambition and ingenuity, appropriate for its titular protagonist, J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), the brilliant physicist who led America’s Manhattan Project during World War II. Nolan and his crew, including production designer Ruth De Jong (Nope), reached for the stars and succeeded in their quest for a pure, tangible vision in presenting one of the most important and dangerous minds of the 20th century – the father of the atomic bomb.

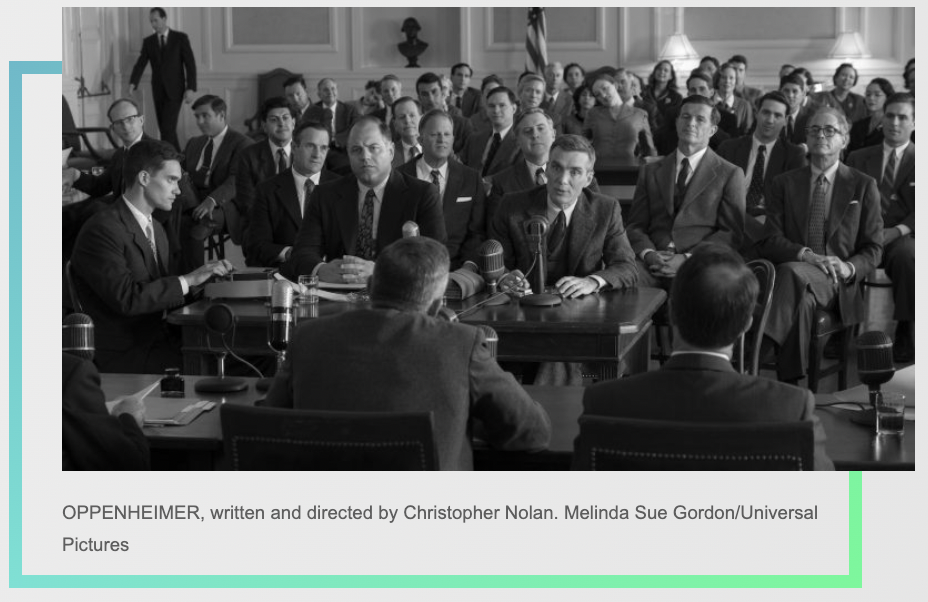

In the brisk and often unnerving three-hour epic, J. Robert Oppenheimer is in a race against the Nazis. The American government enlists him to help them build a weapon of mass destruction, despite his affiliations with communism, which will plague him years after the war. Oppenheimer, both careful and careless in his quest to prove his theory correct, becomes a celebrity when his team succeeds—at a remarkably swift pace— and their achievements a vision of unprecedented horror when America dropped two bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. As Oppenheimer famously quoted from the Bhagavad-Gita after the successful testing of the bomb, “I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

In a narrative that spans decades, Nolan brings Oppenheimer’s inner life to the screen, revealing his thoughts, dreams, and nightmares. The critical and commercial success of Oppenheimer, now extending its run in IMAX theaters due to popular demand, is a credit not only to Nolan but to the incredible crew he assembled to achieve his masterpiece, including Ruth De Jong and her masterful design work.

For a movie that’s about obsession, it didn’t call for it in the process of making it. During a recent interview with The Credits, De Jong reveals the modern touches in the unconventional, idiosyncratic summer blockbuster and why working on Oppenheimer was likely not at all what you might have imagined it to be.

In the case of Oppenheimer, you have to capture both the period and the protagonist’s point of view in these environments. How’d you balance that?

I think there was freedom. I mean, Chris and I wanted to be correct to the periods and bring people right there to that time, to that place. There was no obsession with that from Chris’ standpoint; he was always interested in pushing modernity in the sense that if it was the 1920s, but we were shooting a car that was built in 1931, he’d like the way the 1931 car looked. I’m paraphrasing, but he was like, “I almost find it too distracting because it’s almost like we’re in 1925, and here’s this very boxy, early Americana vehicle when I don’t want to be distracted by that. I wanna make this film timeless with the overarching period correctness, but not to the degree that it’s distracting the film.” I felt very much the same way.

So you were encouraged to depart from the period?

I think a lot of period films can be so full of period objects screaming what moment in time it is. We tried to do the opposite and make it as timeless as possible and peel back and simplify—less is more. There was some specificity where we honed in on it was the creation of the atomic bomb that you see throughout the entire story. Recreating that to its exact specs, the Trinity Tower, everything else, of course, all the houses were in the ilk of the period, but there wasn’t an obsession. I mean, we got to shoot in Oppenheimer’s house, his actual house, but all of that, you take a little bit of creative freedom because you’re never gonna find the absolute exact chair Oppenheimer was sitting in.

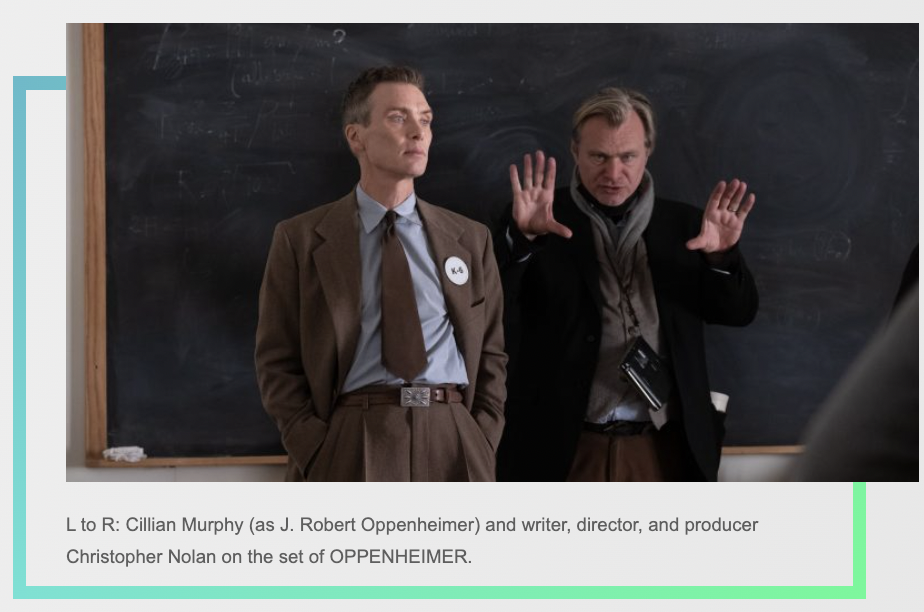

There’s not a single CGI shot in the film. How’d that impact your work? Was it kind of comforting knowing your work wouldn’t be altered in post-production?

It was great because I’m not a fan, either. It’s usually like, “Oh, all you need to do is build this, and don’t worry, we’ll extend this and do this and that.” How it affected our work was we had to be smart with the budget. We had to build enough, but not too much, but enough to make it feel like the town was growing and evolving. I just was smart about building every single building that we did 360 degrees, so you could shoot behind it, in front of it, on the side of it. Chris and [cinematographer] Hoyte [van Hoytema] took full advantage of that. I think it was liberating knowing there was no CGI because you had to do everything on camera, and it created an entirely immersive experience for the cast.

As you said, the job didn’t require obsessiveness, but were there any details you did obsess over?

Early on, I got too engrossed or ingrained in the actual research. We had an incredible researcher, Lauren Sandoval, who did a magnificent job and had so many inroads to the Library of Congress, and the US government, getting all declassified documents as well as all these archives across the country and the world. She was speaking to libraries in England and France and all over the place. We had just incredible photography that a lot of us had never seen before, Chris included. You’re going, “Well, look at the chalkboard behind Oppenheimer and look at this thing.” I remember at one point, Chris was just like, “Ruth, let it go. I’m selling popcorn; I’m not making a documentary.” [Laughs]

[Laughs] That’s a great way of putting it. So, you could be more interpretive of the time, if that makes sense?

It is almost a dream back to the past. There were certain things, like telephones and water fountains, that looked like they were from the 1800s. I would say, “It’s from 1935.” Chris would be like, “Get it out of here,” because it became too kitsch. We wanted almost to be utilitarian. There was a 1970s water fountain, and he was like, “No one will notice. No one.” The minute you start to draw attention and start to dress every corner, it becomes too obnoxious.

How’d you approach the bomb and its surroundings? Who were your closest collaborators for that section of the film?

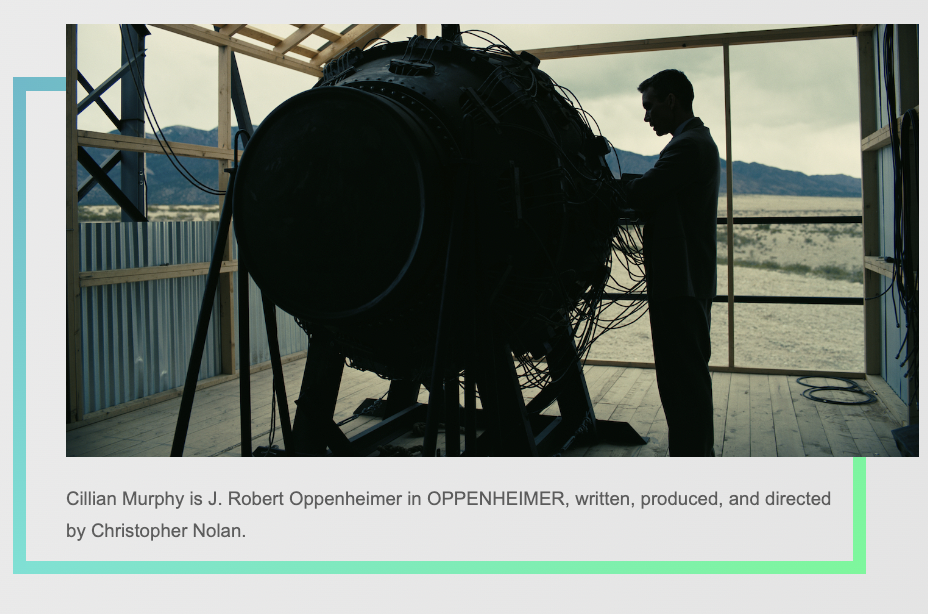

We were all under such a crunch to do this epic movie for very little, you know, and everyone’s like, “Oh, you’re on a Nolan movie?” And I’m like, “No, I might as well be on an indie movie. This is not comfortable. We don’t have cash flowing to pay for things, and we have to be smart about our decisions.” And you know, Chris is like, I only really need to see a couple of bits. Like, when Ciillian’s up in the shed and looking at the atomic bomb, there were just some moments that were very important to Chris, but when I got together with Scott Fisher from special effects, and Guillaume [DeLouche], our prop master, it was like, we have to build this entire bomb.

So, again, he could shoot it 360?

It doesn’t make any sense just to build a piece of it to save some money. This is the main character of the entire film. Chris told us no, but we did it anyway. I think he is forever grateful because then it changed; he ended up following the evolution of this thing getting created, and it became more integral. It was areas like that where we tried to be smart about what we wanted to feature and why, and that just felt so important. Chris didn’t say no because he didn’t want us to build it. He was just trying to help us with our budget. He’s like, “Look, I can be smart on my end and figure out ways to shoot around it.” But we knew at the core; we’re not gonna limit him in that way. That’s not fair.

This article was first published on The Credits