On or around January 1 each year we get a recrudescence of the same old story, a “celebration” of all the works that have just entered the public domain in the United States. It is the story that just keeps on giving for journalists facing a quiet day and searching for filler, the most recent example being Michael Hiltzik’s January 3 column in the LA Times. The “hook” this year is the fact that A.A. Milne’s first Winnie-the-Pooh book, published in 1926, is now in the public domain in the US. In Canada, the CBC jumped on this story, notwithstanding the fact that the work has been in the public domain in Canada since 2007. Although Pooh entering the public domain in 2022 is not directly relevant to Canadians, a story is a story so the CBC interviewed Hiltzik, and embellished its report with quotes from a prominent Canadian academic copyright skeptic. (There are other Canadian experts who could have provided an alternate view but that would not have fitted with the CBC’s one-sided editorial slant of “flaws in US copyright law” and “copyright creep”, speculating on how this might apply to Canada).

The explanation of why a large number of works enters the public domain in the United States on the first of January each year is complicated and has to do with the permutations of U.S. copyright law, and extensions to the period of copyright protection passed into legislation over the years. In the most recent extension, in 1998, where the U.S. sought to bring its period of protection into line with that of the EU (which is “life of the author plus 70 years”), copyright protection was aligned with the EU standard for works published after 1978 and set at 95 years from the date of publication for many earlier works, with January 1 of the 95th year being the trigger date. That means that works published in the US during 1926 fall into the US public domain this year.

In Canada, and in other countries (including the US with regard to more recent works), a work enters the public domain on the first of January of the year following a set period of time after the demise of the author. In Canada, that set period is 50 years, which explains why the Milne work entered the public domain in Canada on January 1, 2007, Milne having died in 1956. That set period is about to change to bring the duration of copyright protection in Canada into line with that of most developed countries, including the US and EU, that is to say, life of the author plus 70 years. This was one of the copyright issues dealt with in the USMCA/CUSMA trade agreement. Judging by the thrust of its report, however, the CBC doesn’t seem to think this is a good idea.

For groups like the Center for the Study of the Public Domain at Duke University, the proclamation of “public domain day” on January 1 of each year is an attention getter. The public domain has been part of the structure of copyright law ever since the first copyright laws were introduced, although there are those who believe that since copyright is a property right it should not lapse, just as other property rights do not expire. From the perspective of a rights-holder, the impending lapse of copyright in a property could be compared to the clock running out on a property lease on which your house has been built. The closer to the expiration date, the less value there is in the property. However, historically copyright has always been a limited property right. The original copyright law, the 1710 Statute of Anne, provided for 14 years protection with a possible extension of an additional 14 years if the author was still living. This was mirrored by the 1790 US Copyright Act. Since then, the duration of protection has been extended for several good reasons, such as providing additional incentives to authors to create (an extended term of protection makes a work more valuable when the rights are licensed or assigned), to providing the incentive for corporate rights-holders to invest in updating and further developing a property.

Those who go to inordinate lengths to “celebrate” a work going into the public domain help feed the false narrative that a work under copyright is one that is “locked up” and unavailable to the public. The Center notes that works falling into the public domain are “free for all to copy, share, and build upon”. That’s true, but a work under copyright is also available for all these purposes through licensing, and/or fair dealing/fair use exceptions. The original Milne Winnie-the-Pooh book has been in the public domain in Canada now for 15 years and I am still waiting to see the explosion of “re-imagined” new works built on it based on the fact that it is no longer under copyright protection. I am not holding my breath for the sudden emergence of new Pooh-based works in the US either. And when authors create new works based on public domain material—guess what? These new works fall under copyright because authors rightly want to protect what they have created. The reality is that one of the main beneficiaries of works falling into the public domain are publishers who can then republish popular works without having to secure the rights. In theory, these works should be cheaper for the public but often they are just as expensive as similar works under copyright, the publisher having fattened its margins rather than pass on the savings to consumers.

We all know that one of the big reasons for so much interest in Pooh is because of the successful Disney animated films. Disney purchased the rights to Milne’s works and characters in 1961 from the Slesinger family who had obtained the rights from Milne in 1930. In 2001 it was reported that Disney bought out remaining royalty rights for £240 million of which £150 million went to the Royal Literary Fund. Since acquiring the rights, Disney has given a whole new life and personality to the Milne characters. (TTFN says Tigger). So, what does the fact that Milne’s 1926 book has entered the public domain (in the US) mean for the Walt Disney Company? Not much. First, only Milne’s first Pooh book is now in the US public domain, not his later 1928 work where Tigger appeared for the first time. But more important, Disney has copyright in the films that it has made, and the anthropomorphic characters that it created, and these rights will last for several more decades. In addition, it has protected some of its IP through trademark registrations as well. And what is wrong with that?

The Winnie the Pooh that most of us know today is the creation of Disney talent, inspired of course by Milne’s book. In the case of Milne’s characters, which were still under copyright, Disney purchased the rights, as it has done for some of its other films like Alice in Wonderland. In the case of many other Disney works, they were based on works or stories already in the public domain, such as Grimms Fairy Tales, published in 1812 (Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella), Hans Christian Anderson (The Little Mermaid) and others including Robin Hood and Pinocchio. While the Disney films and characters are based on the original books, no-one can deny that the Disney studio has imbued these stories and characters with new life and meaning, creating something quite different in the process. (Often the dark endings have been replaced by something more palatable to modern tastes, plus the characters themselves—like the Seven Dwarfs–have been given unforgettable personalities).

The investment in the creation of these works has been enormous, but for the most part so have the commercial benefits. In the process, Disney has brought delight and entertainment to generations of children and their parents. Without the return on investment from its earlier films, Disney would not have continued to be so creative and productive with its most recent generation of animated film releases. Yet somehow, in the eyes of public domain advocates, Disney is at fault for protecting its considerable investments in animated story-telling. Mickey Mouse is a favourite target. But let us not forget that copyright protection has enabled the business model that has led to a wealth of children’s entertainment enjoyed world-wide. Disney will rightly continue to protect its interpretation of Pooh and his friends for many years to come, and we will all benefit.

I could not end this blog without going back to Pooh to highlight his Canadian connection. Most readers in the UK and US will not be aware of this story, and it may be new to many in Canada as well, although it got coverage from the CBC on Winnie’s 100th anniversary a few years ago. Winnie was an orphaned bear cub from White River, Ontario who was purchased for $20 by Lt. Harry Colebourn of the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps as his troop train passed though the town on August 24, 1914, on the way to Quebec to embark for Britain with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Colebourn named the bear Winnipeg (shortened to “Winnie”), in honour of the city where he had been living. Winnie went with the troops overseas and once in Britain, became the mascot of a Winnipeg cavalry regiment, the Fort Garry Horse. When the time came for the unit to be shipped to the fighting in France, Harry decided to donate Winnie to the London Zoo for the duration of the war. Whenever he was back on leave, he would pay the bear a visit. He had originally planned to take Winnie back to Canada after the war, to the Assiniboine Zoo in Winnipeg, but the very tame Winnie had become such a huge crowd pleaser and favourite of children in London that Colebourn made the donation permanent. Winnie’s sojourn at the London Zoo lasted until her death in 1934. (Yes, the real Winnie was a female bear). The full story is recounted in more detail here.

One of the children who regularly visited Winnie at the zoo was Milne’s son, Christopher Robin Milne, who like many children at the time probably played with the bear. Christopher Robin had a teddy bear, named Edward, but apparently soon dubbed it Winnie. When Milne began writing the story of the animals in the Hundred Acre Wood, the chief bear protagonist became Winnie the Pooh. And the rest, as they say, is history.

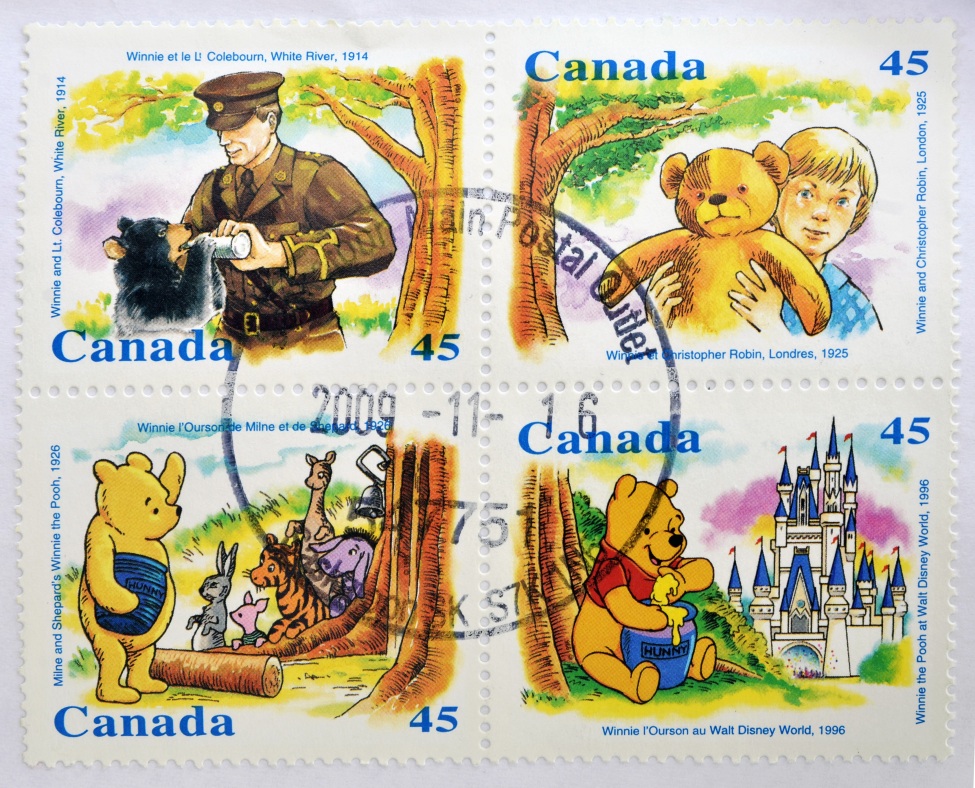

The town of White River has jumped on the Winnie bandwagon and each year holds a Winnie the Pooh festival. There is also a statue, and a park named after the famous bear. The City of Winnipeg also has a statue of Colebourn and Winnie in Assiniboine Park. A few years ago, Canada Post issued a series of four Winnie the Pooh stamps (see blog image above) in conjunction with the Walt Disney company. There was some controversy about this, but not over copyright issues. Canada Post and Disney collaborated fully on the production of the stamps, but some curmudgeonly Canadian nationalists grumbled about images of the Magic Kingdom appearing on a Canadian postage stamp!

Even though Canada can claim some tenuous connection to the famous bear, Pooh truly belongs to the world. The two Milne books on Pooh have been translated into many languages, even Latin. Winnie Ille Pu is the only book in Latin ever to make the New York Times bestseller list. The Latin translation was copyrighted in 1960 by the translator, Alexander Lenard, so the Center for the Study of the Public Domain will not be “celebrating” the release of this edition from the “bondage” of copyright for a while yet. It is interesting to note that the right to translate, or to authorize translations, is one of the bundle of rights conferred on the author or rights-holder by copyright law. Although the work is only now entering the public domain (in the US), that fact that it has been under copyright has not impeded the spread of the word of the “bear with little brain” in many languages around the world. As Pooh would say, “People say nothing is impossible, but I do nothing every day.”

This article was first published on Hugh Stephens Blog