What They are Doing Really Bugs Me

Image: US District Court Filing

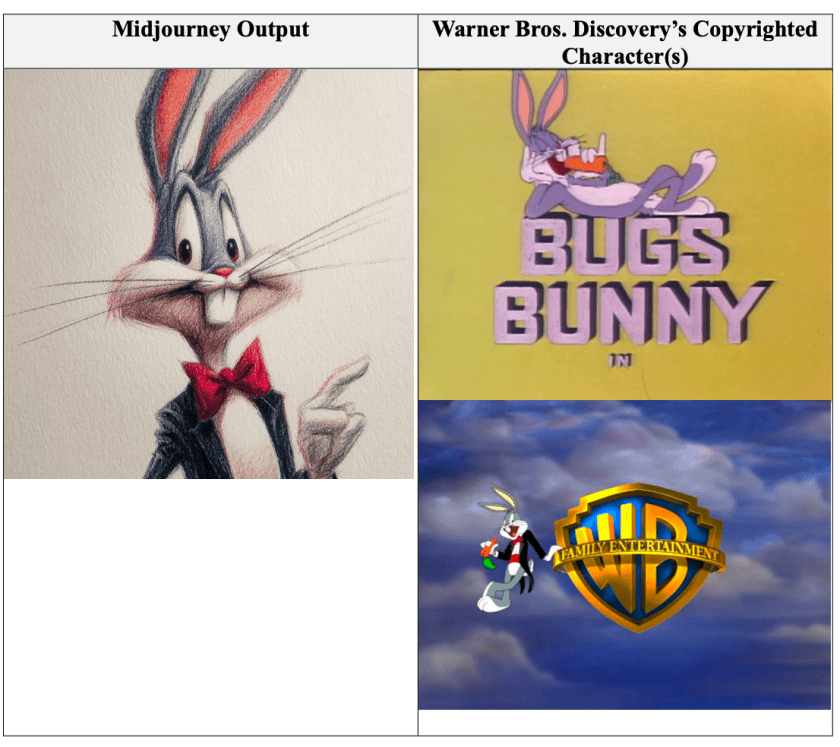

I confess to having been a lifetime fan of Bugs Bunny, that “Wascally Wabbit”, and not just because I worked for Time Warner at one point in my career. His insouciance, his ingenuity and his cultural achievements (have you seen Bugs perform opera or conduct a symphony orchestra?) are legend. Thus it was with some interest that I read the headline in my morning newspaper “Warner Bros. sues AI Company over Images of Bugs Bunny and other characters”. It was based on a generic AP report that appeared in many journals across North America. The AI company in question is Midjourney. Hollywood Reporter has done a deeper dive comparing images produced with Midjourney’s AI program to copyrighted Warner Bros. (WB) images, drawn from the lawsuit submission. This is not the first confrontation between Hollywood and Midjourney. In June Disney and Universal brought a similar suit alleging that the AI company’s image generator produces near replicas of its copyrighted characters.

Just in case you forget what Bugs looks like, Warner Bros. (technically now known as Warner Bros. Discover) has a complete description in its lawsuit;

Many of the Looney Tunes characters are ubiquitous household names, and these characters have expressive conceptual and physical qualities that make them distinctive and immediately recognizable. Bugs Bunny, for example, is a playfully irreverent anthropomorphic gray and white rabbit, who has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Bugs Bunny has an overbite that showcases his two long front teeth, oversized feet with white fur, and is often depicted eating a carrot.

Does this description look anything like the image produced by Midjourney, as reproduced in the filing (see paragraphs 85 and 86), which I have pinched as the image for this blogpost. Scroll up or down to see the full range of characters at issue, ranging from Tweetie to Batman.

Midjourney’s response to the earlier lawsuit, and now to Warner Bros. is that they are not responsible for any copyright infringement that may occur. You see, it is the users of their service who are to blame. Not them. According to their court filing:

“The Midjourney platform is an instrument for user expression. It assists with the creation of images only at the direction of its users, guided by their instructions, in what is often an elaborate and time-consuming process of experimentation, iteration, and discovery.

Midjourney users are required by Midjourney’s Terms of Service to refrain from infringing the intellectual property rights of others, including Plaintiffs’ rights, Midjourney does not presuppose and cannot know whether any particular image is infringing absent notice from a copyright owner and information regarding how the image is used.”

Warner Bros. points out that Midjourney could easily control infringing outputs by (1) excluding WB content from training its AI system (2) rejecting prompts from users requesting WB characters and (3) using technical means to screen images. But instead, Midjourney has become a vending machine for WB content, selling a commercial service powered by AI that was developed using infringing copies of WB works and then allows users to reproduce or download infringing images or videos. These outputs directly compete with WB copyrighted content.

Midjourney’s defence strikes me as similar to arguments used by the manufacturers of guns. “Guns don’t kill people. People kill people.” Except that there are a number of limitations on the kind of gun you can sell, and its capabilities. While the law varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, what is common are restrictions on selling automatic and semi-automatic weapons. The reasons are obvious. While there is a use for some kinds of guns (gun clubs, hunting etc.) there is no legitimate need for unlimited lethality. Not all gun purchasers (like AI software users) can be trusted so limitations are placed on what gun manufacturers are allowed to make available to the public. Similarly, while there are many uses for image-generating AI platforms, there are also legal limits to what is acceptable, such as when AI is used to create child porn. AI companies have agreed to set and enforce guardrails against this, and are clearly capable of doing so. Since, regrettably, not all users can be trusted, to simply to ask them to acknowledge and abide by Terms of Service is inadequate. So, if AI companies can stop some categories of use, they are equally capable of marketing a service that avoids copyright infringement. Enough of the “blame the user” nonsense. Design and market a service that conforms to the law.

Another good example of the “blame the user” excuse is META’s creation of “flirty chatbots” using virtual images of celebrities such as Taylor Swift, Scarlett Johanson, etc. According to Variety, quoting a report from Reuters who researched the issue, the celebrity AI chatbots “routinely made sexual advances, often inviting a test user for meet-ups.” In some cases, when they were asked for “intimate pictures,” the chatbots “produced photorealstic images of their namesakes posing in bathtubs or dressed in lingerie with their legs spread.” Many of these chatbots, which clearly violate the right of publicity of the subjects, were user produced. But users could not produce these images, and cross the line into illegality, unless they were enabled to do so by the program produced by META. META claims that the production of such images violates its rules, which prohibit the direct impersonation of public figures. But of what use is a rule if it is not enforced?

If AI developers design products that are easily misused and then enable (even encourage) their users to do so, it is high time for them to accept responsibility. They are able to establish guardrails; they just don’t want to as it is easier to free ride, while attracting as many users as possible. Midjourney is a good case in point, but Warner Bros has just fired a shot across their bow. Just as Bugs did in Captain Hareblower.

© Hugh Stephens 2025. All Rights Reserved.