“Fair Use” Does Not Justify Piracy

Image: Author

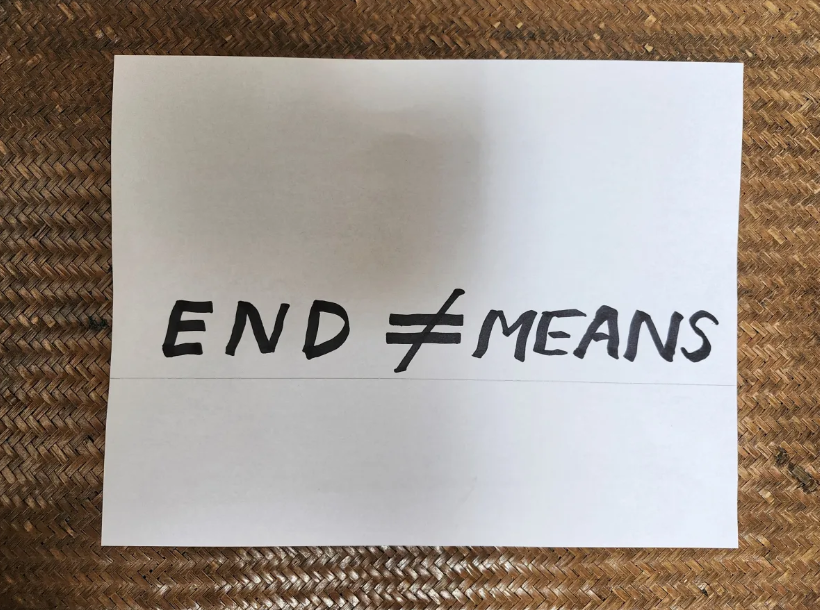

The stunning announcement on September 5 that AI company Anthropic had agreed to a USD$1.5 billion out-of-court settlement to settle a class-action lawsuit brought by a group of authors was ground breaking in terms of its size, and goes to disprove the old adage that “the end justifies the means”. It is still not clear if the “end” (i.e. using copyrighted content without authorization to train AI algorithms) is legal, although preliminary indications are that at least in the US this may be the case. However, even if what Anthropic and other AI companies have been doing is ultimately determined to be fair use under US law—which is by no means certain—downloading and storing pirated content is clearly not legal, even if it is to be used for a fair use purpose. In other words, the piracy stands alone and must be judged as such, separate from whatever ultimate use to which the pirated content may be put.

Ironically, in the end, Anthropic did not even use much of the pirated content it had collected for training its platform, Claude. It seems to have had second thoughts about using content from online pirate libraries such as LibGen (Library Genesis) and PiLiMi (Pirate Library Mirror) and instead went out and purchased single physical copies of many works, disassembling and then digitizing them page by page for its Central Library, after which it destroyed the hard copies. Why go to all this trouble? Why not just access a legal online library? That’s because when you access a digital work, you don’t actually purchase it. You purchase a licence to use it, and that licence comes with conditions, such as likely prohibiting use for AI training. Anthropic would have been exposing itself to additional legal risk by violating the terms of the licence, so instead of negotiating a training licence, they took the easy way out by downloading content from pirate sites LibGen and PiLiMi. Later, having second thoughts, they purchased physical copies of the works they wanted to ingest and then scanned them. But it was too late. The piracy had already occurred.

When the decision in the Bartz v Anthropic case was released this summer, I commented that the findings were a mixed bag for AI developers. A very expensive mixed bag, it turns out. In the Anthropic case, there were clearly some interim “wins” for the AI industry. Anthropic’s unauthorized use of the works of the plaintiffs (authors Andrea Bartz, Charles Graeber and Kirk Wallace Johnson, who filed a class action suit) was ruled by the judge (William Alsup) to be “exceedingly tranformative” thus tipping the scales to qualify as a fair use. In addition, he ruled that Anthropic’s unauthorized digitization of the purchased books to also be fair and not infringing. However, it was the downloading and storing of the pirated works that got Anthropic into hot water. Even though the intended use of the pirated works was to train Claude, a so-called transformative fair use, this did not excuse the piracy. While Alsup did not specifically rule that use of pirated materials invalidates a fair use determination (i.e. he ruled that the piracy and the AI training were separate acts), his ruling exposes a weak flank for the AI companies. For example, the US Copyright Office has stated that the knowing use of pirated or illegally accessed works as training data weighs against a fair-use defence. In short, the end does not justify the means.

The piracy finding was significant because Judge Alsup decreed that this element of the case would be sent to a jury to determine the extent of damages. (In Canada and the UK, judges rather than juries normally play this role). Given that under US law statutory damages start at $750 for each work infringed but can go up to $150,000 per work for willful infringement, Anthropic could have been on the hook for tens of billions of dollars in damages for the almost 500,000 works at issue. (Over 7 million works were inventoried by the pirate websites and downloaded by Anthropic but the limitations on who qualifies for the class action reduced the number of actionable works to just 7 percent of the total). As deep as its pockets are (Anthropic is backed by Amazon), if a jury awarded damages toward the higher end of the scale, the company could have been bankrupted.

Thus, Anthropic had lots of incentive to settle (including keeping the fair use findings unchallenged). As it stands, the $1.5 billion payout, while large in total, amounts only to about $3000 per infringed work, not the minimum but not really financially significant for the plaintiffs. This amount will probably have to be split between authors and publishers, with some of the funds covering costs, so no authors are going to be buying a new house on the proceeds. The real beneficiaries will be the law firms that represented them. The messy process of deciding who gets what that has led Judge Alsup to suspend the proposed settlement in its current form and require greater clarity as to how the payouts will be managed. The number of works eligible for payment is limited by the fact that to qualify they have to meet three criteria;

1) they were downloaded by Anthropic from LibGen or PiLiMi in August 2022

2) they have an ISBN or ASIN (Amazon Standard Identification Number) and, importantly,

3) they were registered with the US Copyright Office (USCO) within five years of publication, and prior to either June 2021 or July 2022, (depending on the library at issue).

Any other works do not qualify. Registration with the USCO is not a requirement for copyright protection but in a peculiarity of US law, without registration a copyright holder cannot bring legal action in the US.

While the settlement has been welcomed in copyright circles, and could set a standard for settlement in other pending cases where pirated material has been downloaded for AI training by companies such as META and OpenAI, it doesn’t settle the overriding question of whether the unauthorized use of non-pirated materials for AI training is legal. With the settlement, the Anthropic case is closed, including with respect to the fair use findings. There will be no appeal, another benefit for Anthropic. However, there are still a number of other cases working their way through the US courts, so the question of whether unauthorized use of copyrighted content for AI training constitutes fair use is far from settled.

The Anthropic settlement, especially its size, has caught people’s attention. It may result in AI developers deciding it is better to resort to licensing solutions to access content rather than risking the uncertain results of litigation. On the other hand, payments like this could be one-offs, a speed bump for deep pocketed AI companies who will continue to trample on the rights of creators if they can get away with it. In the Anthropic case, while the company must destroy its pirated database, it is not required to “unlearn” the pirated content that it ingested. Moreover, even if this case leads to more payments to authors, which would be welcome, there are still many copyright-related conundra to be resolved. It should not be necessary to have to constantly resort to litigation to assert creator’s rights given that, as the Anthropic case shows, only a very limited number of rightsholders benefit from specific cases. Broad licensing solutions are required. This would also help address the problem of AI platforms producing outputs that bear close resemblance to, or compete with, the content on which they have been trained.

While Bartz v Anthropic is a decision that applies only to the US, and only to this one very specific circumstance, it will be studied closely elsewhere in countries that do not follow the unpredictable US process of determining fair use, for example in fair dealing countries like the UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere, and in EU countries. In Canada, the unauthorized use of copyrighted works for training commercial AI models is a live issue. With the possible exception of research, unauthorized use such as that undertaken by Anthropic is unlikely to fall into any of the fair dealing categories (in Canada, they are education, research, private study, criticism, review, news reporting, parody and satire) nor is there a Text and Data Mining (TDM) exception in Canadian law. As Canada and other countries come to grips with the copyright/AI training dilemma, the principle of how content is accessed will surely be an important principle. Just as fair use (if indeed AI training is determined to be fair use) does not justify piracy in the US, licit access is required in Canada to exercise fair dealing user rights, including where TPM’s (technological protection measures, aka digital locks) are in place to protect that content.

Judge Alsup’s decision upholds the important principle that the end (if legal) does not justify the means (if illegal). This is a key takeaway from the Anthropic case, imperfect as the outcomes of that case were. Meanwhile the legal process of determining how and on what terms AI developers should have access to copyrighted content to train their algorithms continues.

© Hugh Stephens, 2025. All Rights Reserved.