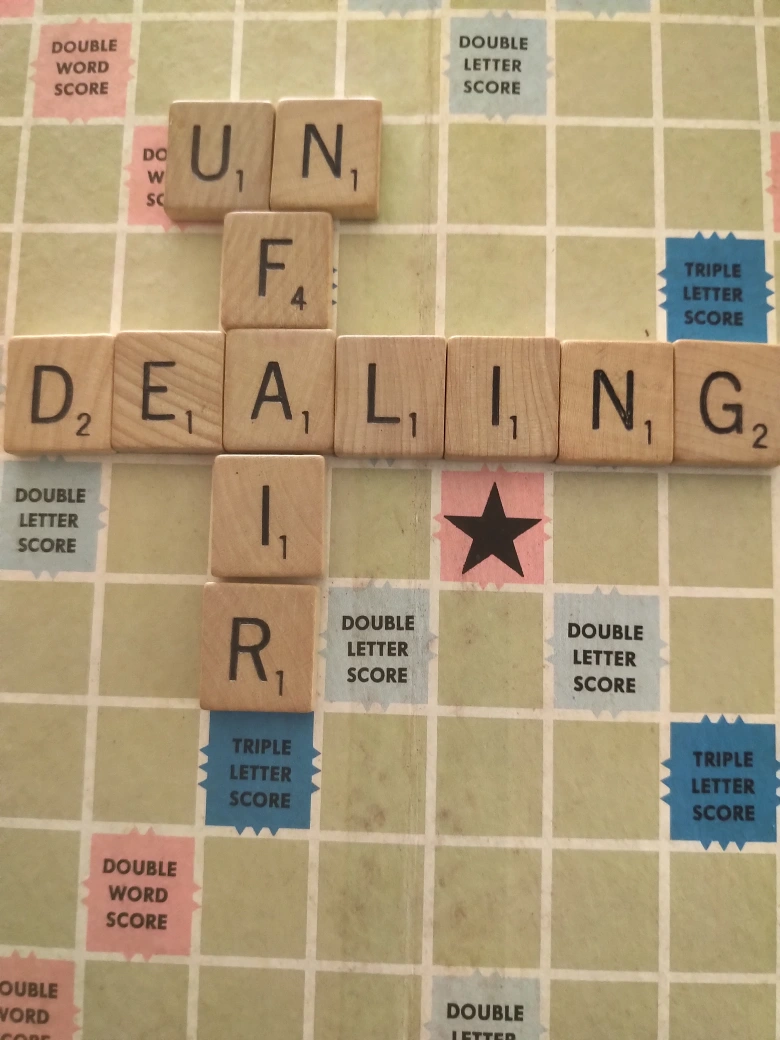

February 21-25 is Fair Use/Fair Dealing week, so proclaimed by a number of participating organizations in the US and Canada and organized by the Association of Research Libraries under the umbrella of fairuseweek.org. As in past years, there will be a series of online events extolling the virtues of fair use and fair dealing. Fair dealing and fair use are firmly embedded as part of the copyright ecosystem and have been for many years, although the interpretation of what constitutes “fairness” is far from static.

This is the definition of fair use and fair dealing from fairuseweek.org’s website;

“Fair use and fair dealing are essential limitations and exceptions to copyright, allowing the use of copyrighted materials without permission from the copyright holder under certain circumstances.”

Fair enough. The term “under certain circumstances” says it all. This is the very crux of the issue when determining whether or not a use, without the permission of the rights-holder, is fair. Courts are periodically called on to determine what is fair and what is not. In the case of fair dealing in Canada, there are a number of “exceptions” or “allowable purposes” where permission is not required. These are research, private study, education, parody, satire, criticism, review, and news reporting. But not just any permissionless use that falls into these categories is necessarily “fair”. Other factors figure into a fairness evaluation, including the amount of the work copied, the use to which the copies are to be put, the nature of the work, the alternatives available, and the impact of the dealing on the work, i.e. whether the copying might have a detrimental effect on potential sales of the originals. These must be weighed to determine if a use not authorized by the rights-holder is legal (fair).

From the above criteria, which are drawn from the six factors to be considered when adjudicating fair dealing outlined by the Supreme Court of Canada in the CCH v Law Society copyright case in 2004, (which in turn resemble the four fair use factors used by US courts), you might conclude that an unauthorized use that (a) involved extensive or even total copying of a work that had been (b) produced explicitly for a particular educational market, like a work used for instruction in a university course, and which, as a result of the copying, (c) had suffered heavy damage to its sales potential even though (d) the work, as a readily available commercial alternative, could be easily purchased or licensed, would not meet the bar for fair dealing, even though it fell within a specified exception such as education. If this is your view, you will be at odds with most if not all of the folks from the Association of Research Libraries who are bringing you fair dealing week in Canada.

Even though this hypothetical work may have been copied, chapter by chapter, in its entirety by different professors for different courses, and even though the sale of copies of this specialized work to students by the university effectively demolishes any commercial market for the work, Universities Canada has declared this to be fair dealing in their view. As a result, most of its members, notoriously including York University, have decided to avoid any payment to rights-holders, refusing to obtain a licence from Access Copyright, the collective that represents authors and publishers, or in many cases to license the works directly from rightsholders. This has resulted in a long-running lawsuit that has pitted Access Copyright against York. While parts of this lawsuit were decided by the Supreme Court of Canada in July of last year, the fair dealing issue remains unclear.

If it’s all a bit arcane to the casual reader, I will try to summarize. Universities and school boards, prior to 2011-12, used to obtain a licence from Access Copyright (AC) allowing them to copy materials in AC’s repertoire (i.e. AC had signed an agreement with the copyright owner, either an author or publisher, allowing it to license the works of the rights-holder and collect royalties on their behalf. These works then went into AC’s “repertoire”). The cost of the licence was based on estimates of the amount of copying occurring during instruction over a given period of time. The licence did not allow for unlimited copying, only copying within specified limits, such as up to ten percent of a work, one chapter in a book, one article in a magazine etc. Copying beyond those limits required further permissions. The licence was based on a per capita cost per student. At one time the fee per university student per year was $26. It is considerably less now due to market pressure to reduce licence fees as a result of the expansion of fair dealing to encompass education.

Under this licensing system, if AC and the users could not agree on a royalty fee, the issue was punted to the Copyright Board of Canada to set a “tariff”. The Board held hearings to determine a fair and equitable royalty rate for post-secondary copying covered under the tariff. Once the Board approved the tariff, it was accepted that it was applicable to all those who used material held in AC’s repertoire unless they had reached their own licensing agreement with the copyright collective. This was the situation that prevailed until about ten years ago. Then it all began to unravel.

In 2012 the Supreme Court of Canada, in a case known as Alberta (Education) v. Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright),ruled that the allowable purposes of “research and private study” should be given a “large and liberal interpretation” in the context of practices prevailing at the time (i.e. teachers copying materials for classroom instruction). In effect, this meant that if a teacher copied short excerpts of materials for use in classroom instruction to supplement the primary textbook, this was an allowable fair dealing because the teacher was exercising, on behalf of students, their “research and private study” rights. That same year the Copyright Modernization Act was passed adding “education” to allowable purposes under fair dealing . As a result of that legislation, Universities Canada backed out of an agreement on a new model licence with AC that would have resolved the issue of institutional copying and updated copyright guidelines for the digital age. The stage was set for a lawsuit to try to settle the issue. When York University refused to pay the interim tariff established by the Copyright Board, AC sued. York’s position was that it had no obligation to pay because its use was either covered by fair dealing, as exemplified by its Fair Dealing Guidelines applicable to students and faculty, or was already licensed.

Round One went to AC in 2017. The Federal Court ruled that York was obliged to pay the “mandatory tariff”, and that York’s use was unfair. It is worth quoting some excerpts from the judgement regarding York’s supposed fair dealing;

(Para 14) “York`s own Fair Dealing Guidelines (Guidelines) are not fair in either their terms or their application”

(Para 20) “The fact that the Guidelines could allow for copying of up to 100% of the work of a particular author, so long as the copying was divided up between courses, indicates that the Guidelines are arbitrary and are not soundly based in principle”

(Para 25) “It is almost axiomatic that allowing universities to copy for free that which they previously paid for would have a direct and adverse effect on writers and publishers”

(Paras 28 and 245) “The complete abrogation of any meaningful effort to ensure compliance with the Guidelines—as if the Guidelines put copyright compliance on autopilot—underscores the unfairness…York`s approach to these copyright infringing actions is consistent with its wilfully blind approach to ensuring compliance with copyright obligations, whether under the Interim Tariff or under the Fair Dealing Guidelines”

(Para 272) “It is evident that York created the Guidelines and operated under them primarily to obtain for free that which they had previously paid for”

(Para 353) “the Guidelines have caused and will cause material negative impacts on the market for which Access would otherwise have been compensated for York’s copying”.

That is all very clear. York’s dealing was not fair. York appealed but this time based its arguments on challenging the mandatory nature of the Copyright Board’s tariff (interim or not). This time they were more successful. The Federal Court of Appeal (FCA) ruled that, based on historical precedent and close reading of the 1988 and 1997 legislation, the tariff was not mandatory when applied to a user even if the user was continuing to make use of works covered by the tariff. This somewhat bizarre and unexpected interpretation undermined the basis of collective licensing in Canada and was appealed by AC to the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC). While negating the mandatory nature of the tariff, the FCA nonetheless upheld the Federal Court’s decision on the fair dealing issue. While the FCA confirmed that York’s copying guidelines were not fair, AC was left with no recourse since it does not have the requisite rights to maintain a copyright infringement lawsuit. While AC collects royalties for rights-holders, it is not a rights-holder itself. Therefore, if a fair dealing case is to come to trial, it has to be launched by a rights-holder. This means that individual rights-holders are required to bring suit for individual infractions against multiple universities, an impossible and nonsensical situation considering the requirements for documentation, which is why collective licensing was established in the first place.

With the Federal Court of Appeal having blown a hole in the fabric of collective licensing by ruling that mandatory tariffs were not binding insofar as users were concerned, the damage was compounded by the Supreme Court when it upheld the FCA’s decision on the (non) mandatory nature of tariffs. With respect to fair dealing, the Supreme Court did not issue a ruling, considering the question moot since York had no obligation to pay the tariff established by the Copyright Board. But the SCC did not stop there. After dismissing AC’s appeal on the mandatory tariff question, Mme. Justice Abella, in delivering the decision, editorialized on the lower court’s earlier ruling regarding York’s Guidelines. While declining to endorse York’s request to declare that its Guidelines were fair, writing for the Court, she noted;

(Para 87) “this should not be construed as endorsing the reasoning of the Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal on the fair dealing issue. There are some significant jurisprudential problems with those aspects of their judgments that warrant comment.”

Although the SCC refused to issue a Declaratory Statement legitimizing the Guidelines, and although she recognized that the SCC was not retrying the fair dealing aspects of the case, Justice Abella then proceeded to cast doubt on the original fair dealing decision against York. She commented that the Federal Court had looked at infringement only from the institution’s perspective and had failed to take into account the user’s right of individual students. This commentary, known in legal circles as obiter dicta, is not binding on future courts but is potentially damaging if and when a fair dealing case is brought by a rights-holder against York or any other educational institution. This will cast yet more doubt on what is–and is not–a fair dealing when it comes to educational copying.

There is no question that the current very broad interpretation of fair dealing in Canada has caused immense damage to the Canadian publishing industry and has lined the pockets of educational institutions at the expense of authors and creators. Instead of spending hundreds of thousands of dollars fighting the representative of authors and publishers in court, and spending millions more to hire additional staff to screen and vet copyright compliance, York and other universities in English Canada could have simply acquired a licence from Access Copyright, as the universities in Quebec have done with respect to AC’s Quebec counterpart, Copibec. The current tariff set by the Copyright Board is $14.31 per student or less than .0004% of the average annual cost per student, amounting to less than four cents a day per student.

There is nothing “fair” about the actions taken by York or the other institutions that have refused to compensate authors and publishers for using their works by prying open the fair dealing exception to the fullest extent possible, aided and abetted to date by the Supreme Court of Canada. The universities should do the sensible (and “right”) thing and license the content they are using for instruction. With the Supreme Court having allowed the gutting of the Canadian educational publishing market, it is incumbent on Parliament to re-introduce some balance. It can do this, as recommended in 2019 by the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage, by limiting the education fair dealing exception–when applied to educational institutions–to circumstances when the work is not commercially available. The Committee also recommended that the Government of Canada promote a return to licensing through collective societies. To do this, legislation will be required to fix the anomaly of mandatory tariffs that are mandatory only for one of the parties, (licensors), but not on users, thereby restoring the viability of collective licensing in the publishing sector in Canada. That would bring some fairness to fair dealing in Canada and would be something to celebrate during fair dealing week next year.

This article was first published on HughStephensBlogs