In They’ve Gotta Have Us now streaming on Netflix, British photographer-turned filmmaker Simon Frederick chronicles the history of Black Cinema by sitting down with some of the people who made that history. Produced by BBC Two and Ava DuVernay‘s ARRAY company, the three-part documentary series blends archival footage with dozens of interviews to survey eight decades of American filmmaking.

“I wanted to hear about the struggles and the successes, but I also wanted to hear the human stories in between,” says Frederick.

To that end, Harry Belafonte recounts the challenges of being a black leading man in 1960’s Hollywood. John Boyega remembers being so broke he took a bus home from the meeting with J.J. Abrams when he learned he’d be starring in Star Wars: The Force Awakens; Whoopi Goldberg explains how Steven Spielberg persuaded her to do The Color Purple. David Oyelowo describes his admiration for Denzel Washington. Moonlight director Barry Jenkins talks movingly about how growing up with a crack-addicted mother informed his approach to his masterpiece.

The series also takes an unflinching look at the systemic racism baked into movie marketing during the forties, when, for example, studios routinely edited out black singer-actress Lena Horne from film prints screened in the south in order to avoid offending white audiences.

Speaking from his London home, Frederick delves into his mission to celebrate the arduous journey made by black filmmakers on their way to becoming key players in 21st-century Hollywood.

You’ve said that watching Moonlight win the Oscar in 2016 sparked the idea of making a documentary about black cinema. How so?

I’d been thinking about this idea for a long time but watching the Oscars on TV the night that Moonlight won, I realized this would be the perfect place to start, as a moment of 100 percent definitive change. It’s not a slave story. It’s not a shoot-em-up. It’s not a comedy. It’s a coming-of-age story and it’s about being gay, which is extremely rare in the black film canon. So I said to myself, “This is something new. It’s a full stop but it’s also a beginning. And that’s when I started to write the story.”

You’re a relatively unknown UK artist yet somehow you got dozens of major black American artists to talk about race and tell some very personal stories on camera. How did you round up the talent?

In our office, we had two walls. One for talent that was confirmed. And the other wall had 85 pictures of everyone that we wanted. That left-hand wall remained empty for weeks.

So how’d you fill it up?

Basically, wrangling the talent was about making your argument so compelling that talent would want to come and be part of this. We worked very carefully on the letters we sent out to agents so they wouldn’t be fearful about allowing their talent to talk about subjects that they believed might alienate their audience. So that was the first step: evangelize the agents.

Once actors and directors warmed up to your project, you conducted interviews in L.A. New York and London. What was your approach to these sessions?

I started out as a photographer so portraiture is at the heart of my documentaries. I think of the interviews as talking portraits. In terms of where people sit, how I sit them, the parameters of the screen, the eye level, the way they address the audience and the lighting — all these things are very important to me. And so with They’ve Gotta Have Us, I wanted to re-invent the talking heads genre, which I think is boring. I never understood why people in documentaries talk to some space off in the distance rather than looking directly at the camera.

They’ve Gotta Have Us documents a shocking level of Hollywood racism in the forties, fifties and into the sixties. For example, studios routinely deleted scenes of black singer Lena Horne in film prints shown to white audiences in the south. Were you aware of those practices?

I didn’t know about the Hays Code, which prohibited people of different races have any kind of romance on screen. But during post-production, the thing that really shook me up was when I learned about Hattie McDaniel, the first black person to win an Oscar as best supporting actress in 1940 for Gone with the Wind. At the awards ceremony, the white cast and crew sat at one table while Hattie sat at a table in the corner of the room. After her speech, Hattie was ushered out [of the venue] through the kitchen. When I heard that, it broke my heart. Black women have been routinely written out of history, so I said to my team, “Okay, we’re going to change the structure of episode one and give Hattie McDaniel her due.”

You spent time with Harry Belafonte, who’s 92 years old. That must have been memorable.

Mr. Belafonte came in on a wheelchair being pushed by his assistant. He got up from the wheelchair, sat on the box and talked for three hours. It was like a complete master class because sitting in front of me was the past, present, and future of cinema, of black culture, black cultural thinking. Here’s a man who walked with Martin Luther King, he knew Malcolm X, he helped their causes. Honestly, I could take that interview alone and turn it into a two-hour piece well worth watching.

The late John Singleton also went before your cameras shortly before he died.

John was amazing. He asked me, “How many hours are you doing and when do you have to deliver? I told him and he was like “Son, they’re trying to kill you!” He texted me that evening. A week later he called me and said I had to stick to my guns if the broadcaster asked me to do things I knew weren’t correct. I’m currently writing a script for a feature, and there’s no way I would have done that if it hadn’t been for John Singleton.

We see that kind of ripple effect throughout the documentary, which shows how Sidney Poitier, Denzel Washington, and Eddie Murphy inspired actors to do their thing. And we also see how Spike Lee inspired Singleton to make Boyz n the Hood in 1991, which in turn spawned a whole new generation of black filmmakers.

Spike not only motivated black filmmakers to go out and do the work, but a lot of people in the industry got their start from Spike. He was instrumental in ensuring that black talent got a chance to make movies, and then that talent went on to help create this revolution or evolution in cinema that we’re seeing now in movies like Get Out.

They’ve Gotta Have Us chronicles massive progress for black filmmakers, but it’s not necessarily a straight line forward, witnessing this year’s Oscars. Only one out of twenty acting nominees was a person of color. On camera, David Oyelowo basically says that the Hollywood studio system still has a long way to go.

The structural mechanisms are not in place, like David says; the political mechanisms are not in place, but what we do have now is a shift in the minds of black filmmakers. During previous periods, I think we had the mindset of children waiting for acknowledgment and accolades from our parents, waiting to get a pat on the head: “Yes you can go play in that playground over there.” But now there are new ways of making and financing films and getting those movies seen and developing audiences. Black filmmakers are saying, “We’ve grown up. We no longer need your permission to tell the stories we want to tell.”

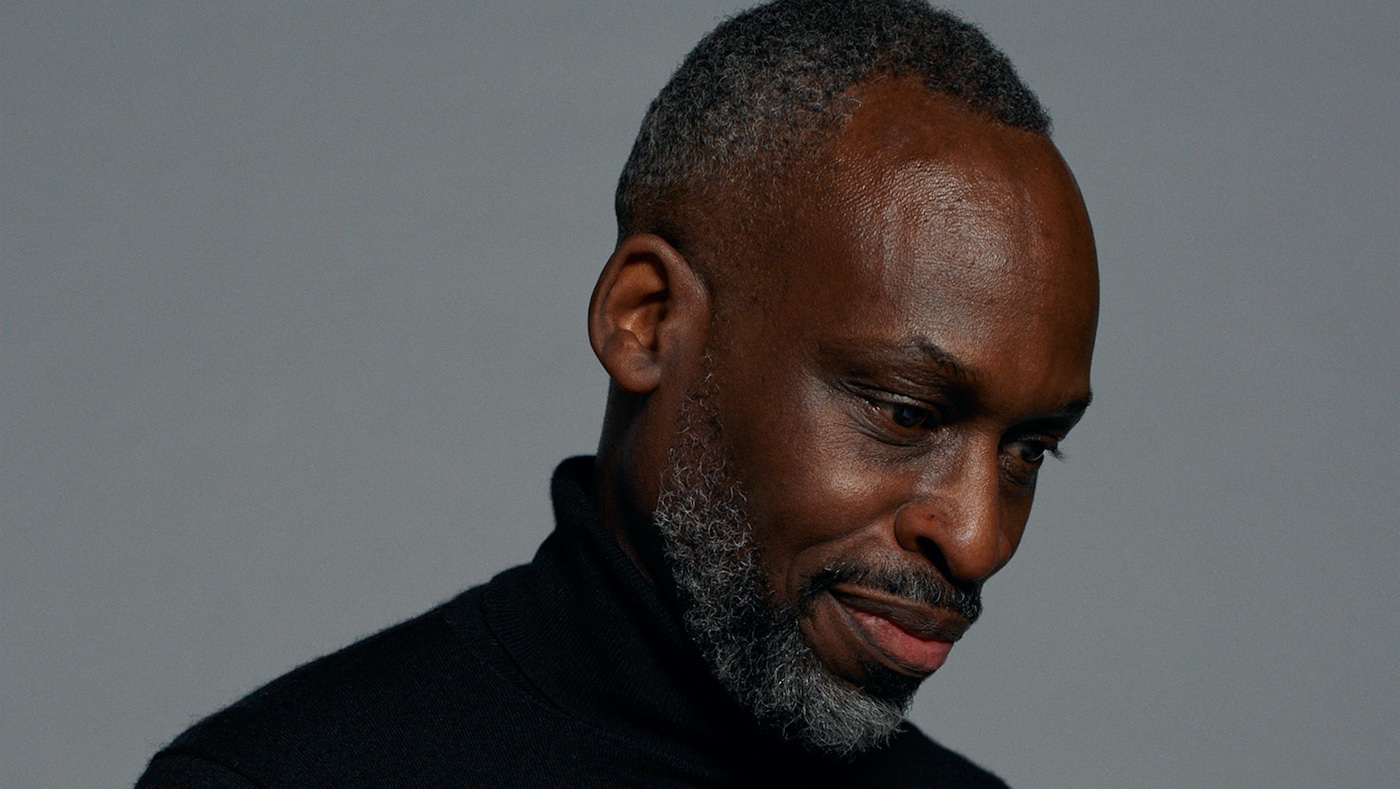

Featured image: Simon Frederick, director of ‘They’ve Gotta Have Us.’ Courtesy Array/Netflix.