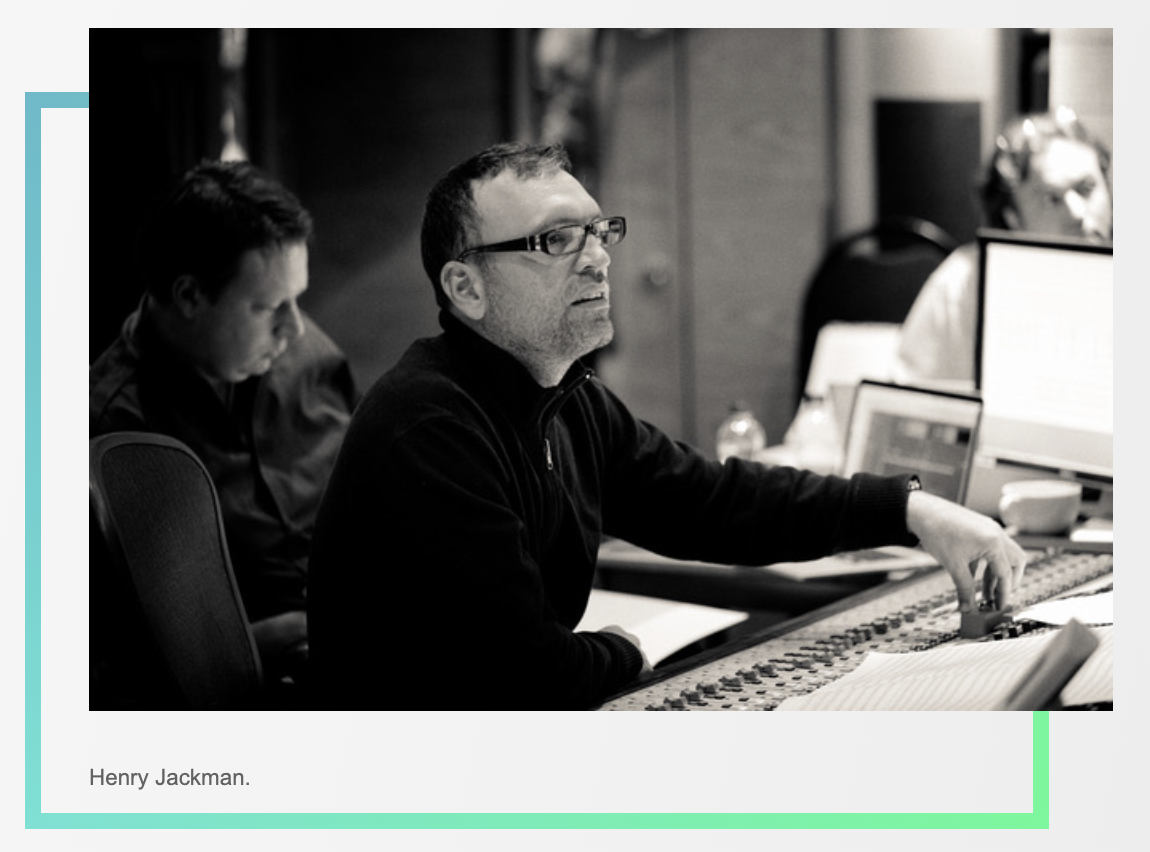

Classically trained at Oxford University, British-born musician Henry Jackman moved to Los Angeles in 2001. Within five years, he’d landed an apprenticeship gig at Hans Zimmer’s music company, and from there, Jackson quickly rose through the ranks to become one of Hollywood’s most versatile composers. Credits range from Kong: Skull Island and Tom Hanks’s tense, fact-based drama Captain Phillips to half a dozen zany animation features, including Wreck-It Ralph. Along the way, Jackson forged an especially fruitful bond with Joe and Anthony Russo, scoring the brothers’ Captain America: Civil War and Cherry, as well as Marvel Studios’ Disney+ series The Falcon and the Winter Soldiers.

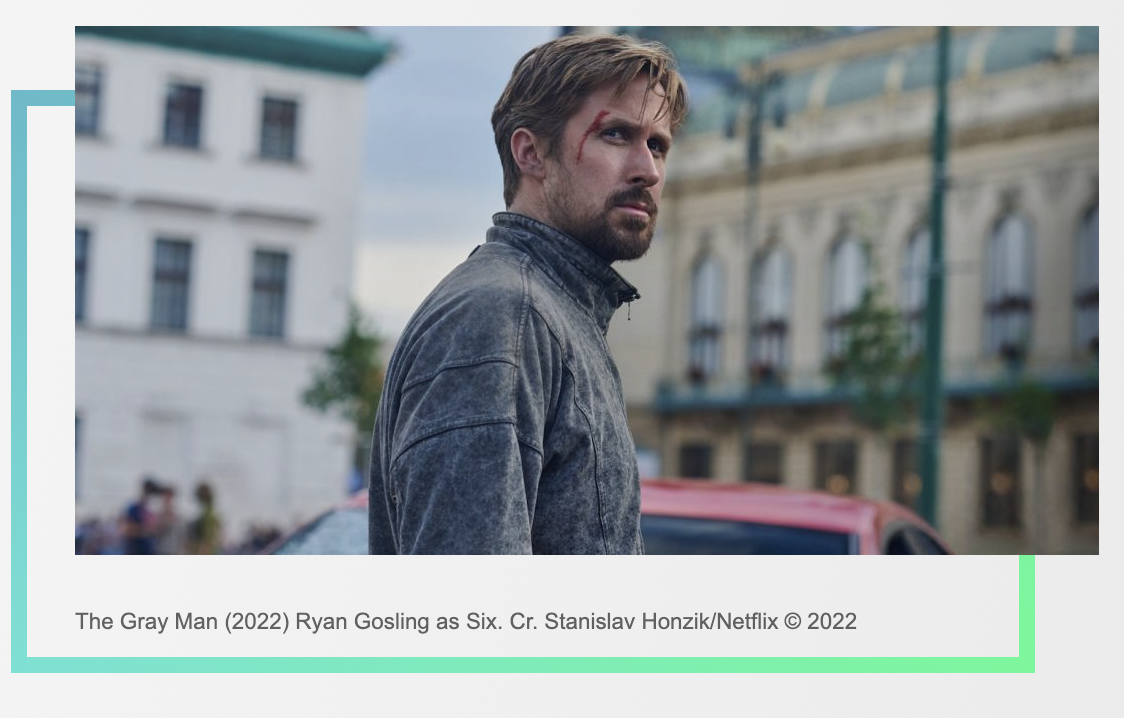

For the Russos’ new Ryan Gosling action movie The Gray Man (streaming Friday on Netflix), Jackman spent months obsessing over a 17-minute suite before seeing a single frame of the film. Jackman explains, “If you’re trying to do something original in writing music for movies, I’ve found that if you just get the picture and go straight into writing cues, you often get distracted by the mechanics of the scene. If you really want to develop ideas, it’s useful to work away from picture.”

From his home studio in Los Angeles, Jackman, assisted by a nearby piano, walked The Credits through his creative process for developing the dark, dense Gray Man score and explained how he juggled music making with his new role as a first-time dad.

Your suite for The Gray Man plays like a theme and variation master class in the way it builds all these elements on top of this relentless core rhythm.

I pretty much have no excuse because I had an inordinate time to do that piece.

Composing an entire chunk of the score before you even see a rough cut — that’s not the way you would normally score a movie, is it?

I certainly don’t always have nine months to do a sort of mega-suite, as it were. I did write a suite for Winter Soldier as a stand-alone piece, but for this one, I wound up with a 17-minute behemoth that contains almost all the ideas you need for the rest of the movie in some form or another.

What inspired the creation of this suite?

It came about because, with my wonderful partner Victoria de la Vega, I had my first child born in March 2021. Trying to be a good dad, I decided I’ll say no to everything until December, when I’d dive into writing cues for The Gray Man. That way, I could change diapers and spend time with this lovely little creature.

How long did your vacation last?

Until Joe and Anthony called while they were making Gray Man and said, “Hey Henry, we shot a scene today having to do with [Ryan Gosling’s character] Six’s internal damage. There’s this ghost in the machine element showing that he’s inarticulate for a reason.” So I went over to the piano, wondering, “What would that sound like?” And I go [Jackman plays three descending chords]. I recorded this on my iPhone, and after a couple more weeks of changing diapers, I said, “You know what? I’ll record this thing properly on the piano.” Then it became: “Now I’ll produce it properly and just get some backward reverb going on it and finish up this little tune-up so it’s ready when we get going on the movie.

What happened next?

Just as I was finishing the piano part, I got this interesting percussion sound going in my head: doong doong doong, doong DOONG. [Jackman imitates a booming kick drum]. I thought Six would want to get going into the action. Once I had this iconic rhythm going, I figured we’d leave it at that.

But you couldn’t leave it alone?

Of course, I went back, thinking, “Let’s develop the groove a little bit.” I spent weeks and weeks engineering all these sorts of hand-baked percussion sounds, so this period of my life was 50 percent parent care, 50 percent mad scientist in the laboratory coming up with cool sounds. And then I went, wait a minute. What about this bass line? [he plays a driving pattern on the low end of his piano] That sounds cool. And then, after the bass line, it’d be a good idea to get these brass chords going. But after I do the brass, I really will stop fiddling with this thing, but then it all just ran out of control because I kept getting all these ideas.

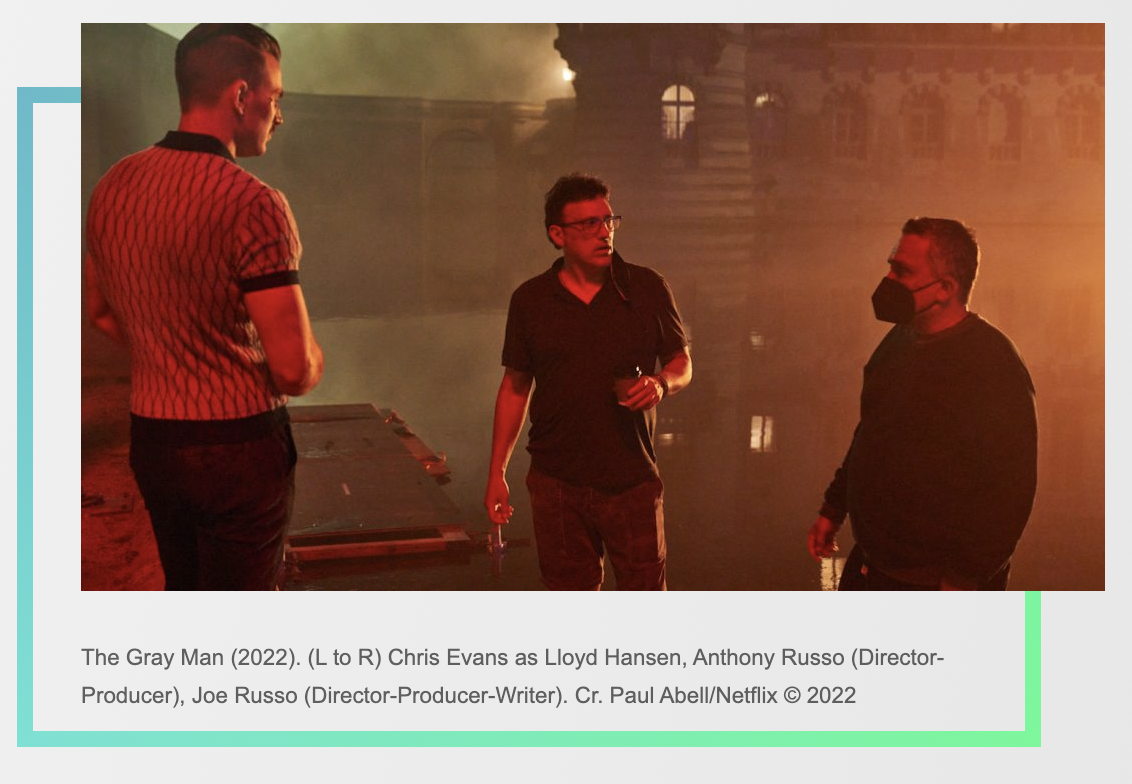

Meanwhile, Joe and Anthony Russo know nothing about your music for their movie?

I didn’t want to push it until I finished because after all the time I’ve spent on it, what if they go: “We don’t think it’s right.” So in December, they called and said, “We’ve got the first cut done, let’s talk about ideas.” That’s when I told them I’ve actually got a little bit of a secret. I’ve sneakily been working away for eight months on this 17-minute epic. They go “What!? Why didn’t you tell us?” I told Joe and Anthony, “I just want one more night of psychological freedom, and I’ll send it to you in the morning.” And thank God, they loved it.

One thing they must have loved is that propulsive groove. It’s perfect for an action movie and reminiscent in a way of the classic rock and roll Bo Diddley beat, except that you drop a measure.

That’s the interesting thing about the groove, which wouldn’t work if it were a club track: It’s in 5/4 [time]. If you were at a rave, people would go, “What the hell’s going on?” Throughout the whole movie, everything’s in five, which makes it a little more esoteric than if the music were straight up four-four.

So you create these massive rhythm tracks at your home studio in L.A. Where did you record the live instruments?

All the orchestra parts were recorded in London at AIR Studios and Abbey Road.

What kind of instrumentation?

It was a lot. Fourteen first violins, twelve seconds, ten violas, eight cellos, six double basses, six trombones, six French horns, three trumpets, treble woodwinds, piano, a bit of harp, saxophone. Sadly we couldn’t do it all at the same time because of COVID rules, but if you add everything together it’s probably 80 people.

It must be exciting to hear all these classically-trained musicians responding to your wild drum ‘n’ bass rhythm tracks.

Very often what happens is you give them a burst of what they’ll be playing up against, but when you actually record, they tend to want just the click track through their headsets. They have very impressive sight-reading skills. It’s pretty amazing to see these guys — and girls — show up for a 10 o’clock session, pull up these pieces of paper with their music cues, put them on the stand and play. It’s the first time they’ve seen the music, and then they’ve got the nightmare of me on the talkback giving them direction, asking for little nuances right after I’ve hit them with like six minutes of music they’ve never seen.

In Old Hollywood, musicians would play to picture, but not now?

You can do that, but these musicians want to focus on the cue. They haven’t got time to watch the movie.

Earlier, you mentioned “hand-baked” bits of percussion. What do you mean by “hand baked?”

What I mean is I’d get a little bit of a recording going and then kick it down an octave, push it through some 1979 synthesizer to make it sound analog, over-drive it, compress it really hard. You constantly finesse the engineering to create this home-baked set of sounds rather than just using some sample collection of known instruments like a high hat or [cymbal] crash. It’s about using weird tricks to make an unusual sound.

Music scores for contemporary action movies often rely on percussion more than the kind of melodic themes perfected by traditional composers in the John Williams vein. Do you prefer one approach over the other?

It depends on what hat I’m wearing. If I’m doing a movie like Big Hero 6 or the Disney thing I’m working on now, there’s melodies flying all over the place and it’s much more in the James Horner/Alan Silvestri vein. But for The Gray Man, the sounds owe more to a drum ‘n’ bass track. I like both approaches. If I only did contemporary action movies I would miss the lush orchestration. If I only did traditional orchestra, I’d miss the gnarly noise.

Where does your versatility come from?

I’ve done everything from 12th-century plainsong to the classical repertoire, plus I went off the rails and got into rave music so I have all these different influences, and that’s been useful. If you know how to use an orchestra and how to put beats together and understand harmony, it potentially doesn’t matter what kind of movie it is because you have all these tools. We’re talking about The Gray Man now, but if you think about an animated film like Wreck-It Ralph, that couldn’t be farther away. As long as I get to do both, I’m a happy varmint.

You broke into film music when you got a job at Hans Zimmer’s Remote Control Productions company in Santa Monica. That’s a plum gig. How did you catch Zimmer’s attention?

Loads of people try to get their music to Hans, but the reason he took notice of me is that I made an album called Transfiguration when I was 29 or 30. At the time I loved Vespertine and Homogenic and whatnot, so I spent a long time on this record that was basically half classical and half re-mix. Hans’ fantastic music editor Bob Badami heard the record and said, “Hans, you should listen to this.”

What did you learn from maestro Zimmer?

I was very green and hadn’t done any music to picture when I got hired, so I had a lowly function that I was very grateful for. The most important thing about that experience was that, unlike any kind of tutorial or college course, I could just sit in a room watching Hans hang out and talk with some of Hollywood’s best directors. That was invaluable.

This article was first published on The Credits