I recently attended a very interesting conference originating from Toronto, called Digital Media at the Crossroads, aka DM@X, where discussion and presentations took place on a range of digital media issues in Canada and internationally. Many of the audience were digital media students studying for degrees in Communications. Among the issues discussed was “site blocking”, a widely used technique in many countries to disable access by consumers to offshore websites distributing illegal or infringing content. The presenter, Kristina Milbourn, is a senior lawyer at one of Canada’s large communications companies. What struck me in particular was her analogy to site blocking as being part of the necessary “rules of the road” for navigating the internet. I thought it was an insightful and creative way to present the issue. (See image above).

We often refer to the internet as a “highway”. All highways have rules to which its users are subject, for the common good. We all need to stay on our side of the road, signal when we are making turns or changing directions, obey traffic signs and signals and so on. There will always be a small minority who choose to ignore the rules, to the detriment of the rest of us, and for these people there are sanctions. To ensure that the laws that we all need are enforced, penalties are issued subject to a process where the accused has the opportunity to rebut the charges. The internet is not much different. Site blocking, and its cousin, dynamic blocking injunctions, fit into this framework.

Site blocking is gaining traction in Canada, with the initial site blocking injunction issued by the Federal Court in the GoldTV case having being upheld on appeal. While site blocking has proven to be effective in deterring consumers from accessing copyright infringing content in countries where it is routinely used, such as Australia and the UK, it is less effective in situations where blocking needs to occur in real time. (More on this below). Pirate content sites typically establish themselves in jurisdictions beyond the reach of domestic law precisely to make it difficult for content owners to have them taken down. Sometimes they are ad supported; in other cases they will actually sell “subscriptions” to consumers, offering content that they have not licensed for a price that legitimate competitors could not match. A recent report by AVIA, the Asia Visual Industry Association, noted that illicit streaming websites and apps generate an estimated US$1.34 billion in annual revenues through advertising. Access is provided to consumers through offshore websites, often enabled with codes that are provided to “subscribers”.

The most effective way to stop this practice is to disable consumer access by requiring online service providers (who are, admittedly, innocent third-party actors) to block content at their servers. In many countries, including Canada, this happens through a court order; in some others the order is issued by a regulatory agency. In both cases, there is an identified problem, an application, a review of the facts, and a hearing where evidence is presented, and an opportunity provided for the target website to rebut the claimed infringement. In almost all cases, the respondent (resident offshore) does not contest the application. Most ISPs have found that the process is not particularly onerous and almost all cooperate. It is not irrelevant that some of them are vertically integrated companies and have their own content assets to protect.

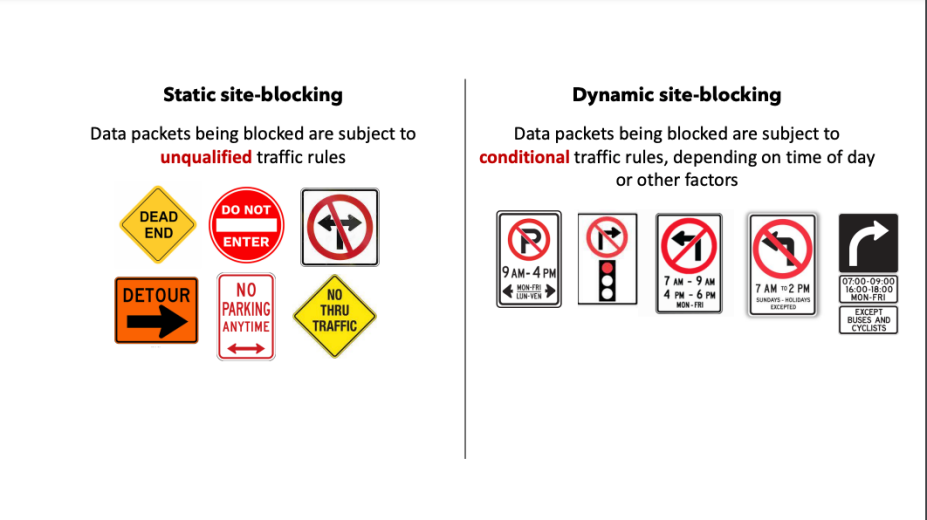

The blocking orders are granted to ensure the smooth functioning of the internet highway. They clarify that access to illegal content will not be tolerated, and they impose the necessary blocks to ensure that the rules are respected. These rules of the road are required to protect the integrity of the ecosystem that creates content for consumers. They even help protect the consumer from self-inflicted harm because many pirate websites are also known to spread malicious advertising, spyware and ransomware as part of their “unadvertised” offerings. Using the traffic analogy, these “static” blocking orders are similar to unqualified traffic rules. Stop. Do Not Enter. No Access. They are static in the sense that they target a specific site with a specific blocking order.

The problem with static blocking orders is that they take some time to obtain and can be circumvented by the pirates by moving to a new internet address. It then becomes a game of cat and mouse. While site blocking orders deter most casual users, really determined consumers of infringing content will search for, or wait to be informed of, the new IP address to get their “pirate fix”. This is particularly prevalent in piracy of sports broadcasts, where pirate providers will switch the source of their feed within the game, once blocking begins. The most effective remedy is to follow the path of the pirates and block the new sources in real time. The technical means are available to do this, but the Achilles heel is the need for court approval. It is no small task to document the case for a site blocking order. It must be precise, and the target must be clearly identified. But what happens when the target shifts? Clearly, in a situation of piracy of live sports events there is no time to go back to the court to ask that the order be amended. The answer is to request a dynamic site blocking injunction.

Dynamic injunctions target the content rather than a specific Internet address, thus allowing the blocking order to shift to whatever address the pirated feed is coming from. It has been successfully used in the UK where piracy of English Premier League soccer broadcasts is all too prevalent. In Canada, Bell Media, Rogers Communications and other broadcasters have applied for a dynamic site blocking order to protect their broadcast rights for National Hockey League (NHL) games. That application is still pending before the courts, with a ruling expected early this year. Coming back to our traffic analogy, whereas static site blocking orders require that data packets be blocked according to pre-determined, unqualified criteria, dynamic orders allow data packets to be blocked subject to conditional traffic rules, depending on the time of day and other factors. Instead of a “Stop” sign, it is more akin to a “No Parking between 7 am and 9 am” sign, or one that prevents a left turn between certain hours on certain days. Both have their utility, depending on the nature of the content to be targeted, just as both fixed and conditional traffic rules are necessary to allow us to use the roads safely.

Site blocking is not a new technique although it is relatively new to Canada. Its usefulness goes well beyond disabling access to copyright infringing content. If last year’s discussion is any guide, the new “Online Harms” legislation expected to be introduced shortly in Canada will include site blocking as one of the measures that can be employed to combat harmful and illegal online content, such as promotion of terrorism and sexual exploitation of minors. Some complain that any blocking of content online is a violation of net neutrality and plays into the hands of autocratic regimes by legitimizing blocking of content. Neither of these arguments is convincing, in my view.

Net neutrality is a principle in which online service providers, who perform a role similar to “common carriers”, should avoid discriminating against or favouring some content or communications over others, particularly with respect to content in which they have a commercial interest. It does not mean that they have an obligation to transmit illegal content any more than the telephone company is obligated to put through calls that a subscriber wants blocked. As for the argument “If we do it, this gives the Chinese licence to do it”, I would make two points. First, the Chinese don’t need any western examples to erect the “Great Firewall of China”. They are masters at it and have already done it. Second, any targeted blocking in western countries is governed by transparent rules overseen either by the courts or independent regulatory agencies, with all kinds of due process built into the system. The same is clearly not true in China or in other jurisdictions that unilaterally decide to block outside content. We need to deal with real problems present in our economies, and not worry unduly about the supposed precedential effect.

While site blocking is becoming a regularly used tool in many countries, surprisingly it is absent in the United States, largely as a result of the misinformed campaign back in 2012 to “Stop SOPA”. SOPA was a piece of draft US legislation (Stop Online Piracy Act) that opponents claimed would have allowed “Hollywood” to censor the internet. All sorts of dire predictions were circulated, including chilling user-generated content, overreach by law enforcement, the demise of e-commerce and technical infeasibility. It was even claimed that SOPA would “break the internet”! On January 18, 2012, a large number of websites, including Wikipedia and Google, went dark during “Blackout Day” to illustrate the purported threat. Legislation that had enjoyed widespread support from lawmakers suddenly became toxic. Members of Congress ran for cover. The legislation was dead and buried, never (so far) to return. The fact that site blocking has been implemented in over 35 countries around the world, and yet the internet is still working (the last time I checked), is proof of the wild-eyed hyperbole that was flung around by opponents of the legislation.

The absence in the US of the kind of rules of the road that have worked so well elsewhere has made it more difficult to combat piracy in the United States. According to a recent study by MUSO, reported in Dataprot, the US is the world’s biggest source of illegal online downloads, almost 28 billion, (followed by Brazil and India), many of them from offshore sites. Targetted, transparent, court-sanctioned site blocking would surely help tackle this widespread problem. A very recent study (January 26, 2022) by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), a Washington DC based non-partisan think-tank, has argued that “A Decade After SOPA/PIPA, It’s Time to Revisit Website Blocking”. The ITIF study documents the success of site-blocking in combatting online piracy in numerous countries around the world, and concludes with a series of recommendations for US lawmakers.

Meanwhile, back in Canada, we’ll have to await the results of the court deliberations on the dynamic blocking orders for hockey games and should soon see what blocking mechanisms are included in the Online Harms legislation. New rules of the road.

Site blocking is helping to maintain good order on the roads and prevent the mass transport of illegal goods over the internet highway. Like the highway code, properly regulated site blocking is to everyone’s benefit (except the offshore pirates). But let’s not worry about that. After all, the rules were made to protect those who contribute to society, not those who rip it off.