AI-generated artwork has been on the rise for quite some time with varied experiments such as Walter Thompson’s The Next Rembrandt and Obvious’ Edmond De Balamy both of which required a sophisticated software specially designed for this purpose, a varied dataset and a collective of intellectuals all working towards the desired result.

Up until the advent of easily accessible text-to-image AI software such as Dall-E 2, Midjourney, Simplified, and the likes AI-generated artwork has been for those with heavy pockets.

Now, commoners with bare minimum knowledge of AI can just sign up to any of these platforms and create art. The burning question which arises is where or with whom will the copyright for such artwork rest? And upon delving deeper into the details of the subject, we will wonder what would be the nature of work done in such circumstances and which bundle of copyrights will it accrue?

Upon a simple reading of Section 2 (d)(vi) of the Indian Copyright Act, 1957, we understand that

“author” means, – In relation to any literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work which is computer-generated, the person who causes the work to be created

Thus raising the question, who causes the artwork to be created in text-to-image generations? Is it the person who has created the software? Or the person who entered the text prompt and refined it to produce the desired result? Or the computer programme (AI) which converts the text into the final artwork?

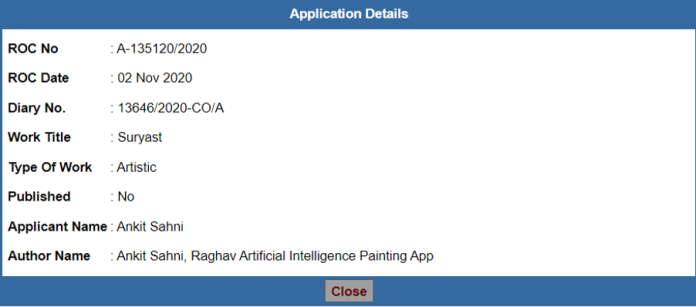

As far as India is concerned, it has been seen in the case of ‘Suryast’ an artwork co-created by robust artificially intelligent graphics and art visualizer (RAGHAV) and Ankit Sahni, that the copyright office shall not grant sole authorship to a computer programme. In fact, it did consider granting co-authorship for the same when included with a human – in this case Ankit Sahni, but later issued a withdrawal notice seeking information about the legal status of RAGHAV.

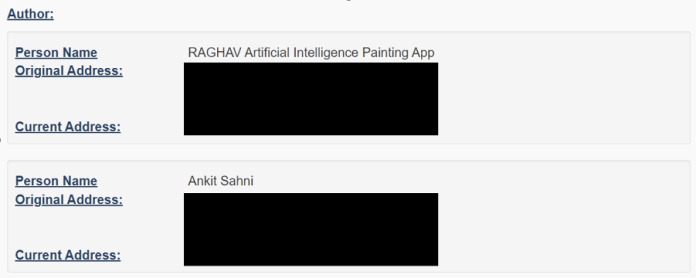

However, we can now see that as of the time of writing this article, the painting has been granted registration as an artistic work with its authors specified as Ankit Sahni and Raghav Intelligence Painting app. The same has also been registered in Canada with co-authorship recognized as in India.

A snapshot of the details obtained from the Indian & Canadian Copyright Office websites is attached below.

Details as obtained from the Indian Copyright Office Website.

Details as obtained from the Canadian Copyright Office Website

There is no provision in the Indian Copyright Act that specifically states that authorship is restricted exclusively to humans so there is ambiguity in the matter.

In fact, in Ramesh Sippy v. Shaan Ranjeet Uttamsingh & Ors., the Bombay High Court held that “so far as authorship and first ownership of copyright in a cinematograph film is concerned, it can be any legal person – an individual, a Partnership firm, or a company who has invested and has taken the risk of failure/ loss of investment.”

The essence of copyrights is that an ‘idea’ cannot be safeguarded due to the virtue of its intangibility. However, once it is converted into an expression fixed into a tangible medium, it can be granted a copyright. One can say that the intention of the Copyright Act is to safeguard ideas once they are presented in a tangible medium where it is possible to do so, i.e. once the ideas have been expressed.

This is something we can understand easily with films wherein scripts can be copyrighted before they are utilized to produce cinematograph films.

With respect to paintings, traditionally it is an artist who comes up with an idea, makes it in a rough draft to work from, and then the final artwork – all by themself. Therefore, there was never a need to grant separate copyrights for separate stages of this process.

However, with the advent of AI art, do we now need to consider separate copyrightable components?

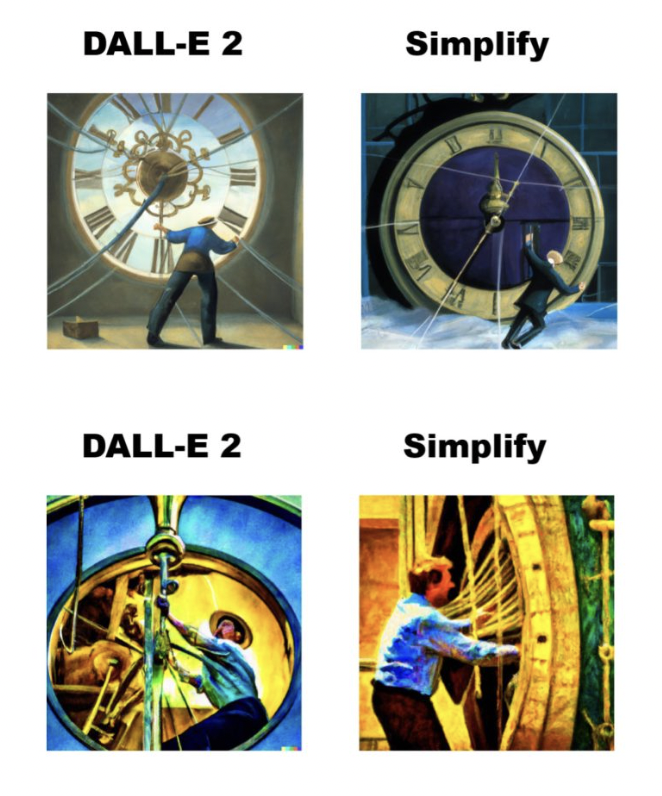

Let us delve into the practicality of the matter; I used AI-based text-to-image software, DALL-E 2 and Simplify to create artwork based on the same text prompt:

“an impressionistic painting of a man pulling out a beautiful rope from the inside of a big fully-functioning clock”

As we can see, the artistic input referring to the angle of perspective for the image, the time of day, the colours to be used, the shape and placement of all the requested components have all been decided by Artificial Intelligence. There is no true artistic involvement on my account to guarantee me a copyright for the said ‘artistic work(s)’ and there is no provision by which a non-human can receive exclusive authorship for the work.

The only basis to protect this visual art from being recreated is protecting the literary work entered into the software.

If a person generates artwork through a purely text-to-image generative model such as those mentioned earlier, and the idea i.e. the string of words which are typed into the programme are such that the artwork i.e. the AI-generated expression of the idea is a well-received artwork. What stops another to use the same string of words with a few or no modifications into the same or a different AI software and recreating an expression for the same idea?

Here are a few unique artworks made by creators:

An italian town made of pasta, tomatoes, basil and parmesan #dalle2 #dalle pic.twitter.com/iEaIaGwIz5

— Best Dalle2 Pics (@Dalle2Pics) May 23, 2022

#dalle2 #dalle” – twitter user @djbaskin_images

Olive oil and vinegar drizzled on a plate in the shape of the solar system

🪄#dalle2 #dalle pic.twitter.com/ZN5yMfJRxP— Danielle Computer Images 💿 (@djbaskin_images) April 27, 2022

Got access to DALL-E – here, have a medieval painting of the wifi not working pic.twitter.com/OSj2gl3US5

— Benjamin Hilton (@benjamin_hilton) April 27, 2022

All the artwork, though stemming from a truly unique and original concept, once published can be recreated by anyone using the same string of words.

Here are the same recreated on Dall E 2 using similar or the same text prompts as tweeted by the users:

“medieval painting of a man complaining to another of the wifi not working”

Since the artworks, though expanding on the same idea, look distinctly different or at least dissimilar from one another, it will be very difficult to prove that the artworks are not original.

However, when we take into account the human effort put in to create such artwork, we realize that there is no originality in the idea i.e. the string of words entered into the software.

Section 2(o) of the Indian Copyright Act, 1957 provides an including definition as it reads: “literary work” includes computer programmes, tables and compilations including computer [databases];” As I emphasized, the provision is left open for evolution; the judiciary can interpret any work which it sees fit under the intent of the legislature.

Though text prompts do not fall under the traditional definition of ‘literary work;’ is granting literary copyright to it the only way to protect text-to-image generation artists? In fact, Section 2(ffc) defines a ‘computer programme’ as a “set of instructions expressed in words, codes schemes or in any other form, including a machine readable medium, capable of causing a computer to perform a particular task or achieve a particular result;”

So one may even argue that the text prompts entered into the AI systems are computer instructions and therefore open to protection as ‘literary work.’

Needless to say, all of the above is pure speculation due to the complications brought in by Artificial Intelligence and the Indian Copyright Act is going to need some big changes to take us forward into this new age.

About the author:

Siddhant Sanghavi is a journalism graduate currently pursuing an LLB from Government Law College, Mumbai, and a career in Intellectual Property Rights. He is a freelance copy and content writer and a passionate volunteer at Shrimad Rajchandra Love & Care – an NGO which enjoys a special consultative status with the United Nations Economic & Social Council.

This article was first published on IPRMENTLAW