All Quiet on the Western Front, Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 novel that lays bare the harsh brutality of war through the eyes of a naive youth fighting in the German trenches during WWI, is considered a literary classic. So Frank Kruse admits some hesitation when director Edward Berger told him he was doing a modern retelling. That disappeared after Kruse read the script. Though the challenge would be daunting, he wanted to be the film’s sound designer and supervising sound editor.

Kruse’s instincts proved correct. Hailed as one of the best films of 2022, All Quiet on the Western Front recently won seven BATFAs, including Best Film and Best Director. Kruse, along with Lars Ginzel, Viktor Prášil, and Markus Stemler, was honored for Best Sound. The sound team (with the addition of Stefan Korte) is vying for an Oscar in the same category. In total, the film has received nine Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture.

During a Zoom interview, Kruse detailed the important role the sound played in heightening the horrors of the battlefield and the emotional toll war takes on those who fight it.

What was the strategy for the sound design?

I love to support the production sound mixer on projects by recording wild tracks — vehicles, crowds, whatever sound is on set. This is really hard to recreate in post-production. This was at the height of COVID. They were shooting in the Czech Republic. The borders would be closed. Travel wouldn’t be easy. I worked as a production mixer myself for 10-plus years. I know the focus during a shoot is capturing dialogue. There’s rarely time for sound. I made a list of items that would be impossible to source later. Then I went through the script with Viktor, the production sound mixer, and flagged all this stuff. Luckily, Edward is a huge fan of recording wild tracks. He was up for directing the wild tracks himself, having the extras run and scream, do takes of them dying, rolling in the mud. That was a godsend.

Approximately how much sound was captured during the actual filming?

I think it was eight-plus hours of wild tracks. Unheard of for a film of this scale. Viktor had two, sometimes three mics mounted on the main characters. One mic would be leveled all the way up to capture the breathing and the close-up exhaustion. Another mic was gained way down for screams so they wouldn’t distort. The mics locked up, giving the sounds this documentary feel. That became a base layer for the entire design work. But we didn’t want to go overboard — you know, the cliche of spooky drones and designy ambiances — stuff like that. We tried to find metaphorical naturalistic sounds for the emotional moments.

How did you research WWI sounds?

World War One is tricky. I tried to find actual recordings from that time. Wax cylinders had been invented, so it was possible to record sound. At Britain’s Imperial War Museum, I found reconstructions using a technology called sound ranging. But they were done later with modern sounds.

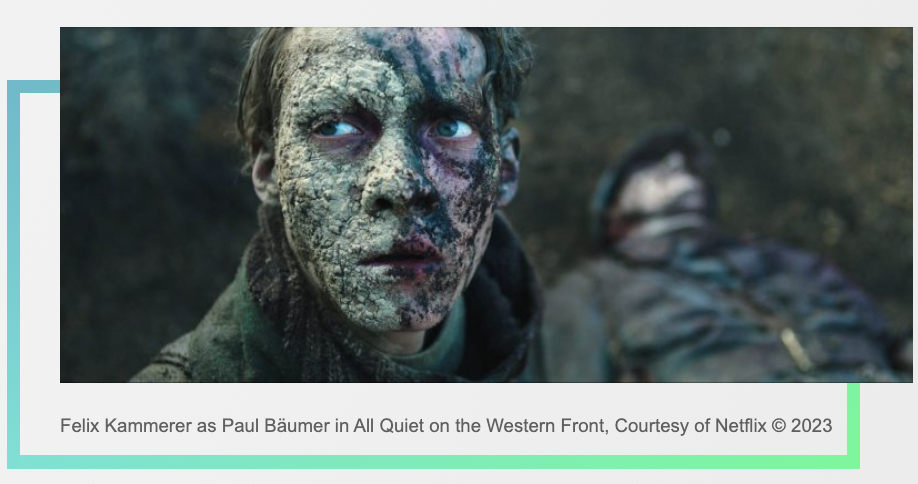

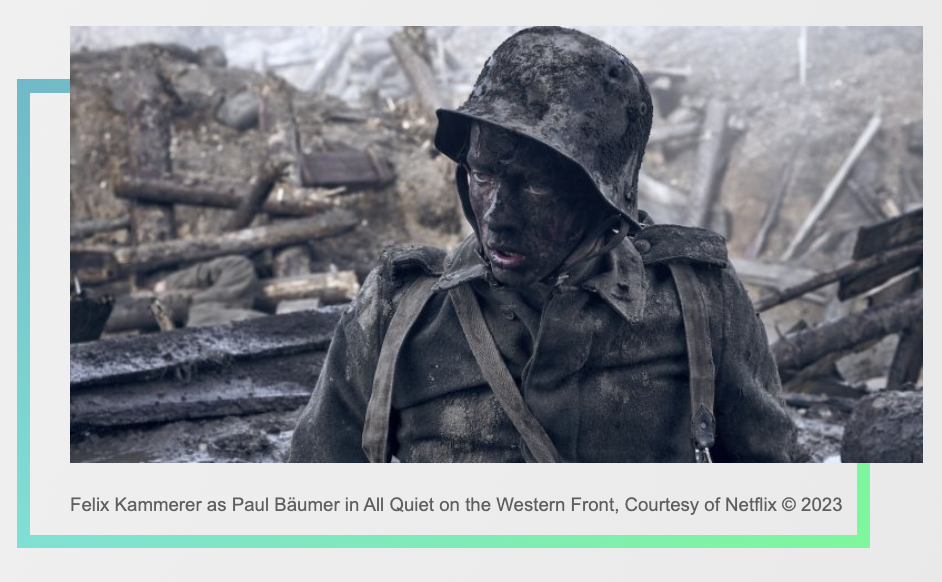

So I dug deeper and found an article quoting letters written at the front to relatives back home. They described the horror of the sound very graphically. That became a big source of inspiration. We realized that it wouldn’t make sense to create sounds that were technically correct. We decided to tackle the soundtrack from an emotional side. The story is told so much through Paul Bäumer (Felix Kammerer), the main character. It was about incorporating a subjective soundscape that connected the audience as the camera ran next to him.

How was that accomplished?

The way it was shot really helped. Most of the onscreen effects were done in-camera. The first cut was full of bullet impact explosions, dirt explosions, etc. We used all the gunshot explosions from the production recordings.

What did you layer in?

I call them shell shock moments. When Heinrich (Jakob Schmidt) gets killed hiding behind the tree stump in the first battle, this extreme panic grips him. The background battle sounds get muffled and go away. Only the main sound element is left. We did that sound by scraping and dragging microphones through dirt. We wanted a certain sound for his panic, as if his body is being pushed through the soil — the sound you hear when your ears are literally covered in sand or dirt.

There’s a similar moment in the tank attack when Paul sees his friend Albert (Aaron Hilmer) being burned by the flamethrowers. Everything goes away. His voice stays close and untreated — almost like it’s in this quiet bubble. The sound creates this moment of peace while horrific things are happening. We always try to go against what you see in a subtle but organic way. Personally, I think it is less interesting when all the departments do the same thing at the same moment. It leaves very little space for an audience to find their own emotion for that scene.

How did Voker Bertelmann’s score impact your design

He came on board a little later than we did. I did a layout of an early sequence where the uniforms are recycled. We see them taken off dead soldiers and refurbished for the next batch of 18-year-olds getting ready to die.

It’s a metaphoric symbol for the industry behind this war. Edward wanted a sound for that. You hear the sewing machines low and pounding like steel mills. That morphs into the real sound of the sewing machines with close-ups of the needles. Eventually, it turns into what sounds like an endless burst of machine gun fire.

I sent that layout to Voker. He introduced another rhythm over that sequence using a harmonium. I found the sound I had made was clashing. So I changed the pitch and tuned it to his music. We tried to find moments when the music did a better job and where the effects were more efficient in telling the story. We never wanted to do the same thing at the same time as the music.

What sounds were the most challenging?

The battle scenes were a huge challenge. There was just so much going on. The tank sound was challenging. We designed it as an emotional element rather than as a technology. These thanks were strategically useless. They barely moved two or three kilometers an hour. They were meant for psychological warfare — to tell the enemy, “You can shoot at us, but the bullets won’t harm us.” We had a wooden toy car. In a weird, funny coincidence, we found when we ran it across a metal ventilation shaft; the wheels resonated in this howling, groaning way — almost like a whale. It became the main element for the tanks. Viktor had wired the tanks with multiple microphones. The original recordings had a rhythmic cadence coming from the metal tracks. We layered them in. It’s always these happy accidents and experimentation in the foley studio.

Any favorite scenes that you worked on or particular sound moments you’re proud of?

I must say, some of my favorite scenes are the quiet ones. I love the moment at the end of the film when Kat (Albrecht Schuch) is in the forest. He looks up into the sky and the (leafless) trees. We added the wind blowing through the trees, shaking the leaves even though there aren’t any. It was going against the visuals to create a dream — past the war, at home with his wife. It’s so peaceful. I really like the contrast.

This article was first published on The Credtis