When Chris Nolan wrapped Tenet in 2919, actor Robert Pattinson gave him a book of J. Robert Oppenheimer speeches as a parting gift. That tome led Nolan to Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.” For the next three years, Nolan used the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography as the foundation for what critics are hailing as his most mature, emotional work.

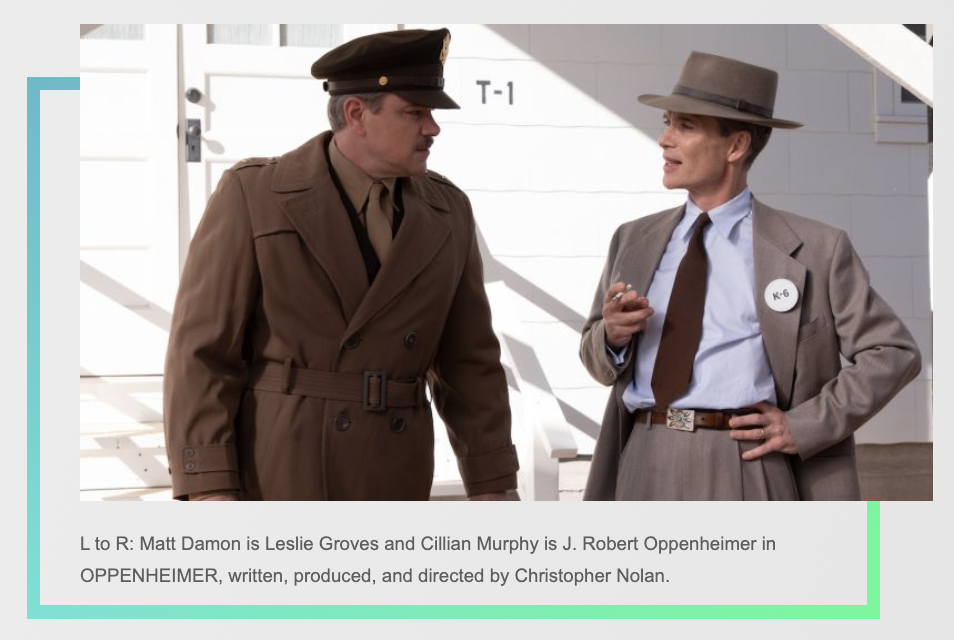

Oppenheimer stars Cillian Murphy (Peaky Blinders) as the brilliant physicist who was tapped to run the Manhattan Project, the United States ultimately successful effort to build the atomic bomb. Oppenheimer and his team developed the weapons of mass destruction that were dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Nolan told The Credits that he thinks, despite never publicly apologizing or expressing any guilt over the horror his weapons caused, “all of his actions from 1945 onwards are the actions of somebody truly suffering under an immense weight of shame and guilt.”

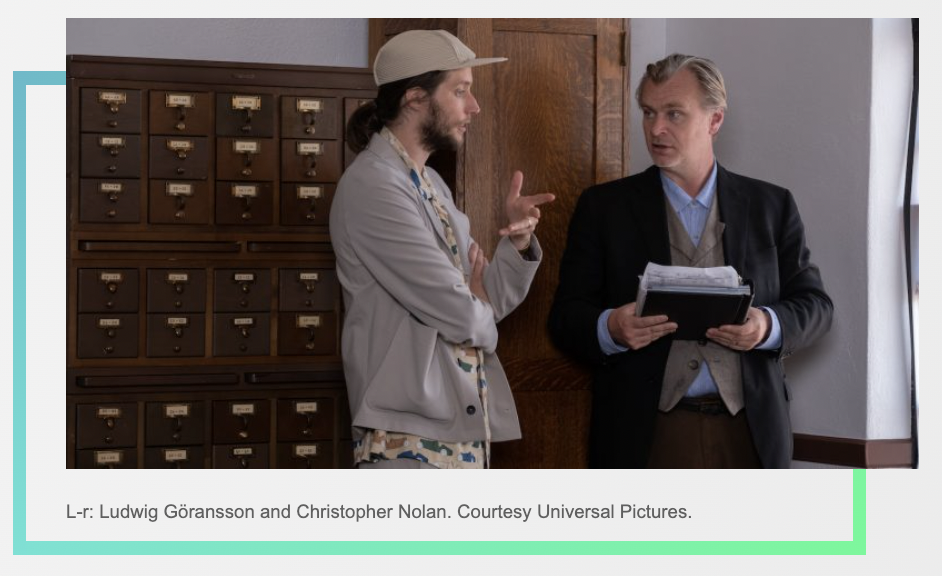

Several months before he started filming, Nolan called Oscar-winning composer Ludwig Göransson. “Chris never talks about what he’s working on,” says Göransson, who previously scored Tenet. “The phone call is out of the blue. ‘Hey, I’ve got a script—do you want to read it tomorrow?’ I had no idea what to expect. I go over and read the script. It was a jaw-dropping moment like you’re watching the world through Oppenheimer’s eyes, living the world through his mind. And I realized that’s what the music needs to do. It needs to channel the whole spectrum of his emotions. That was a big challenge: How do you put all these different types of emotions into the music?”

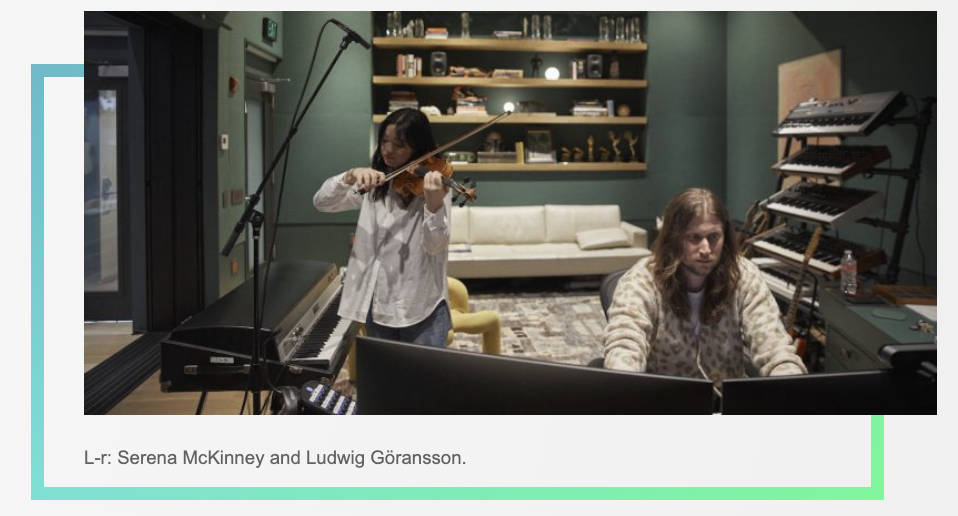

The answers can be heard in Göransson’s intense orchestrations for Oppenheimer, co-starring Matt Damon, Emily Blunt, and Florence Pugh, among others. Göransson, who spoke to The Credits about his Black Panther: Wakanda Forever music, talked about how he collaborated with his violinist wife, skipped traditional percussion, and faced one of the biggest challenges of his career by setting imagery of atomic particles to music.

With Black Panther, you cited the singer Baaba Maal as a key inspiration. In creating the music of Oppenheimer, did you also have someone like that who helped focus your efforts?

Yeah, it was actually my wife Serena McKinney.

How so?

She’s a very accomplished violin player, and one of Chris’s first ideas for the music was that he wanted solo violin to portray the character of Robert Oppenheimer. Especially since it’s a fretless instrument, the violin can go from the most melodic, romantic tone to a neurotic horrific manic vibrato within a split second, so I worked a lot with Serena on this. Experimenting with Serena and doing this music together was a great opportunity.

How so?

She’s a very accomplished violin player, and one of Chris’s first ideas for the music was that he wanted solo violin to portray the character of Robert Oppenheimer. Especially since it’s a fretless instrument, the violin can go from the most melodic, romantic tone to a neurotic horrific manic vibrato within a split second, so I worked a lot with Serena on this. Experimenting with Serena and doing this music together was a great opportunity.

The string section produces this signature motif that sounds like something the layman might call a “smear.” What do you call that effect?

I would call it string glissandos. It’s these micro-tonal glissandos where one violin goes down, and maybe two go up to create a kind of cluster. You hear violins in horror movies played in this way, but I talked to Chris about this: what if you take that idea and play [the glissando] with the most romantic, beautiful tone? You can tell the audience that something horrific is about to happen and kind of dive down [imitating the ominous “smear” glissando], but then you land on a beautiful note, a haunting note. That is what we wanted to embellish about Oppenheimer’s personality. His confidence is pretty high, but he also has some inner demons.

Having worked on Tenet and now Oppenheimer, what’s it like collaborating with Chris Nolan?

Chris has a crystal-clear image of what he wants to achieve and how he wants to get there. That being said, he’s incredibly open to my input, so there’s this exchange of ideas that allows us to push the boundaries of what we can do. And one thing that makes the work so successful is that he invites me into the project early on.

How early?

For about three months before he started production, I’d meet with Chris once a week and show him about ten minutes of [new] music. By the time he went off to shoot the film, Chris already has three hours of my music.

The music at this point would be in demo form, right?

Yes. Maybe the first months, it was just violin experiments, going into the studio with Serena and recording this microtonal “smear.” In the second month, I started writing themes on piano, violin, strings, and harp. I’d record these melodies and textures as demos.

During pre-production, did you get to see any concept art or visual information?

A couple of weeks after I read the script, Chris invited me to a screening at an IMAX theater to watch visual effects he’d made with Andrew Jackson, experiments with atoms swirling around, and that kind of stuff. I go into this darkened theater and get hit in the face with fluorescent lights and things I’d never seen before. It had a big impact on me: “I want the music to sound like that.”

Once Nolan started principal photography, did you get dailies or any footage of what he’d been capturing?

No. Sometimes I’d get a phone call, “Hey, this one piece we worked on, can you change the ending to an up note, or can you add a minute to this or put more tempo on it?” After three months of shooting, Chris gets back and goes into the editing booth with Jennifer Lane, and they start cutting the movie. They used all the existing music I had written.

Wow! All those music cues you created during pre-production wound up in the rough cut?

Yeah. When I see the rough cut, all my music was already in there, which is great because most filmmakers put together a first cut using a temp score that takes music from already existing movies. I think that creates difficulties down the line because you’re taking [musical] DNA from a world that already exists. It seems to me not a very creative way to work.

Where did you record the final score?

We took two hours and fortysomething minutes of music to the scoring stage at Warner Brothers and recorded it in five days with the Hollywood Studio Orchestra, which has some of the best musicians in the world. At its peak, we were 40 string players, eight horns, three trombones, one tuba, three trumpets, and a harp.

All those instruments but no percussion?

No drums. One of the first things Chris and I talked about is that we didn’t want to have any sense of military nuance to Oppenheimer’s character because that’s not where he’s coming from. We didn’t want that [drum sound] to drive his character at all.

Did you use other methods to get that driving feel typically provided by percussion?

We had footsteps, we had the stomping, we had the bomb going off — so much more of a visceral experience. It was cool to see how the music and the sound design went hand in hand with each other. Also, we had the cellists use a technique called collegno, where they [rotate] their bows and use them like sticks, which creates a percussive sound during the nuclear reactor sequence. And then there’s this metallic ticking, which sounds like someone’s tapping a pencil on the bomb — that’s one of our musicians hitting a little metallic thing, almost like a cup.

What was the most challenging piece of music to record?

The piece of music with the atoms swirling. I never thought we’d be able to record that in one continuous take because there are 21 tempo changes. But my wife has been sitting in on these recording sessions for twenty years, and she knows the musicians. She said, “I think you can do it; We just have to give them a different type of click in their headphones so when they record, they get the new tempo before it happens.” On the third day, we gave the musicians a different click in their headphones, and they did the whole piece of music in one take with all those tempo changes.

It must be exciting to hear this huge orchestra of world-class players performing your music live.

One of my favorite parts of the process is seeing how it all comes alive. When you have forty or fifty people in a room together, creating this ambiance in the air — it’s something that’ll never be replaced by computers. The music changed when we started recording with live musicians. They made everything so much more dynamic.

This article was first published on The Credits