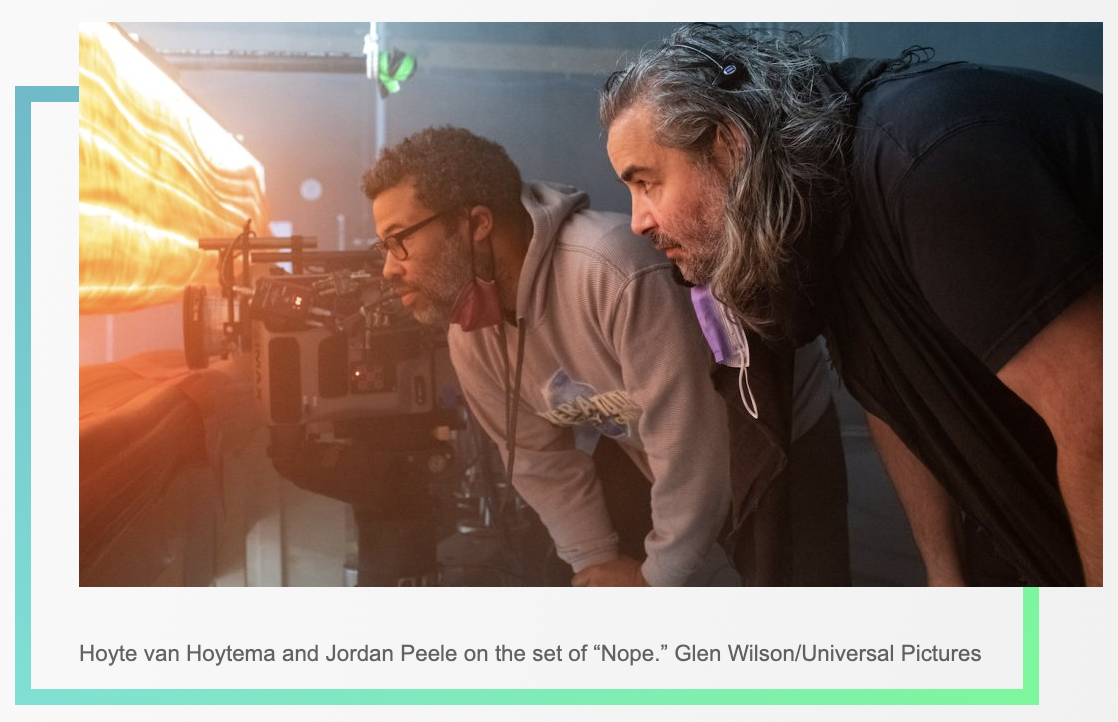

Cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema failed to get into two Dutch film schools, so he worked in a soap factory, played in a band, and survived unemployment as a self-described “slacker” before finding his creative footing at a renowned cinema academy in Lodz, Poland. Since then, he’s made up for lost time through collaborations with A-list auteurs, including David O. Russell (The Fighter), Sam Mendes (Spectre), and Spike Jonez (Her). Working with Christoper Nolan on Interstellar, Dunkirk, and Tenet, van Hoytema embraced the director’s passion for big-screen stories enabled by IMAX cameras, and now, he’s teamed with Jordan Peele to shoot the writer-director’s contemporary western-meets-extraterrestrial thriller Nope (opening Friday, July 22).

Speaking for undisclosed reasons from an enormous warehouse in London, van Hoytema talked about capturing the night sky, creating a sense of spectacle, and taking cues from movies that inspired Nope‘s sumptuous visuals.

Over the past ten years, you’ve demonstrated excellent taste in directors, which continues now in your first collaboration with Jordan Peele on Nope. How did you guys get together?

Jordan and I talked about previous projects, but circumstances never timed out. When Jordan came up with Nope, the stars aligned and we started talking. I had a hunch it could be a cool collaboration.

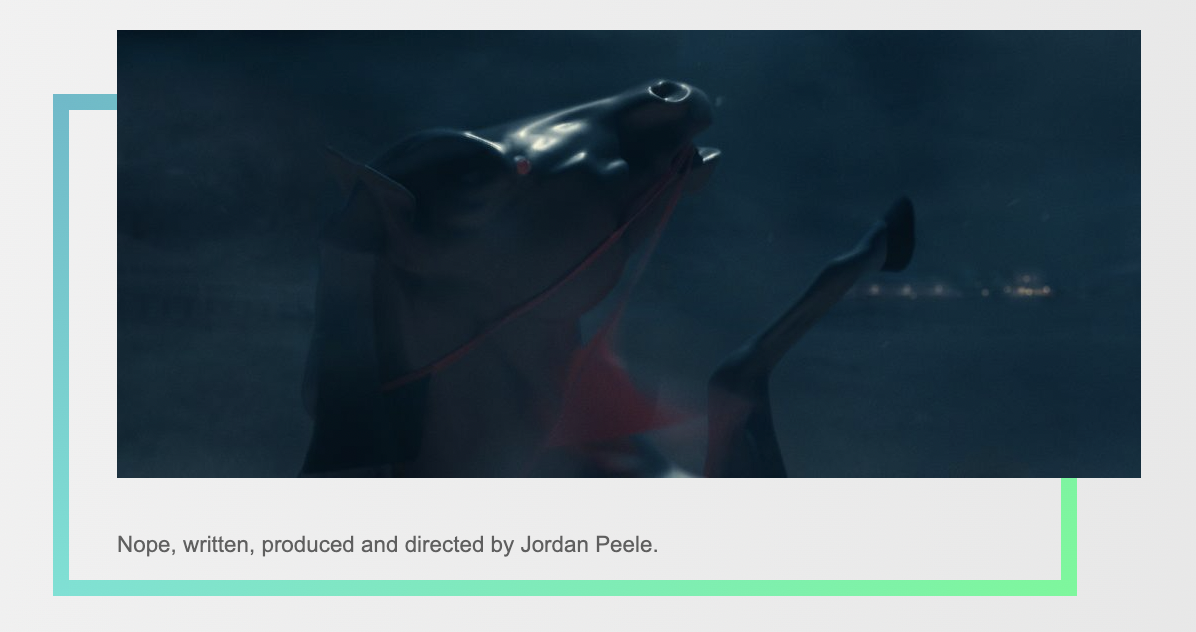

Nope deals in part with the very nature of spectacle, and given your previous IMAX projects with Chris Nolan, you would seem to be well-suited for crafting work on an epic scale. What was Jordan’s creative brief regarding Nope?

Creative briefs are never brief. When you talk to an interesting director, it’s never something where they go, “I want this and I want that.” It’s more of an ongoing conversation. But from the beginning, it was evident that Jordan wanted to expand, to make his canvas bigger, to challenge himself, to understand what spectacle is, to shoot on the big formats for the big screen. He wanted to find the best possible way to shoot this story in an uncompromising way. He never said, “Oh I want to work with you because you shoot with the biggest cameras out there,” but he liked the fact that I’d worked on 65 millimeter.

Biggest cameras out there being IMAX. Roughly how much of the movie is shot in that format?

It’s a lot. Thirty to forty percent. If you see the movie in an IMAX theater, those sequences suck you into the film in a very visceral way.

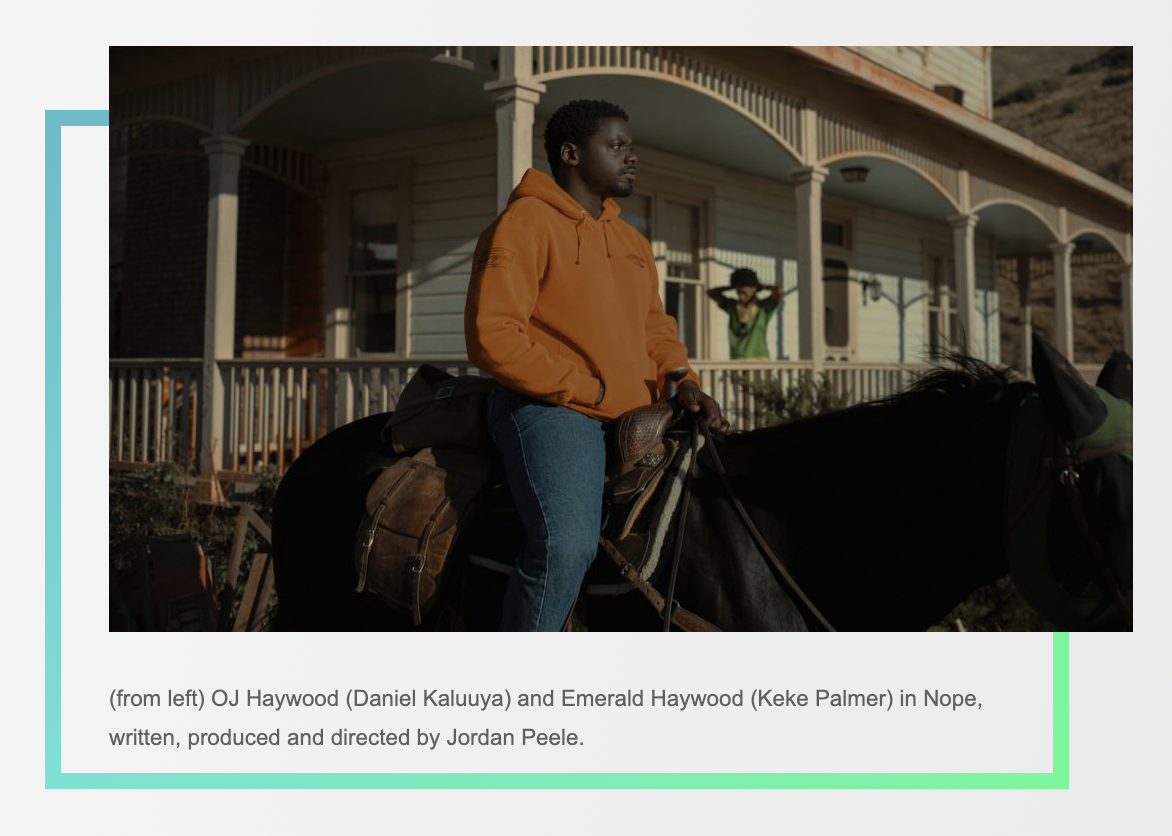

Nope feels in some ways like a western, with the wide open spaces, the big sky, the horses. To inform that look, did you and Jordan reference Hollywood westerns?

We referenced many films. Of course, we had to watch Lawrence of Arabia. Jordan projected the early King Kong movie for me in black and white We also watched the beautiful uncompromising films from the seventies and eighties. Spielberg’s Jaws and Close Encounters were huge inspirations in the way they presented original stories on a big screen so that they became events and spectacles in that way. We watched Heaven’s Gate because of the horses and the dust! We’d just throw references at each other and explored how you may unconsciously harvest certain things from movies you love. Funnily enough for us, it always came back to spectacle.

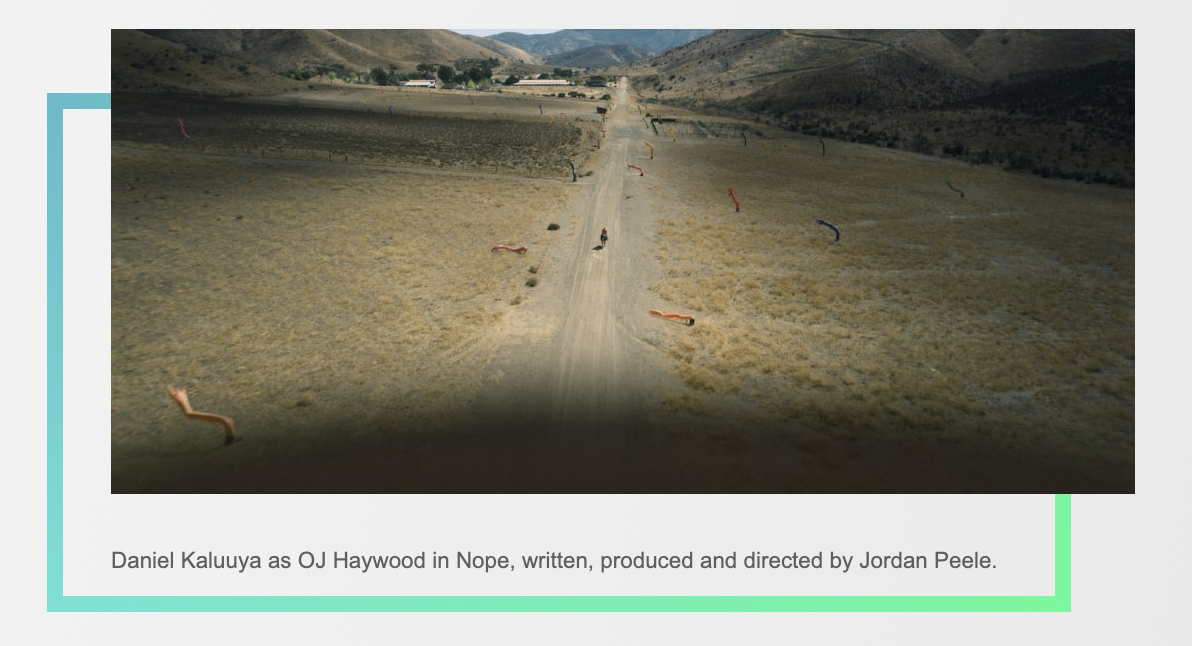

You filmed Nope in the southern California desert east of Los Angeles, outside of Santa Clarita?

Just past Santa Clarita, in Agua Dulce.

And that landscape plays an important role in this movie. How did you use your cameras to bring out the power of nature?

The best example I can give you is the night shots. On one of our first [location] scouts, Jordan and I stepped out of the car at night, turned the lights out, and walked into the middle of this valley. There was a tiny red blinking light blinking on a telephone tower in the distance but otherwise, no light. So your pupils start dilating. Suddenly you start seeing details in the hills around you, the stars in the sky — you experience the expanse of nature. We loved that feeling, which also becomes a very scary feeling in the context of the film. We both thought it was very special but also impossible to film because if you light an area at night with conventional lighting, everything around it will be dead. I started obsessing over how to capture the darkness of the night but somehow see through it. We developed a new technology that went through a lot of evolutions, but in the end, we figured out technically how to do it. The result is the look of our night, which I like to believe is unique. And that all came from wanting to re-create the experience Jordan and I had on that first scout.

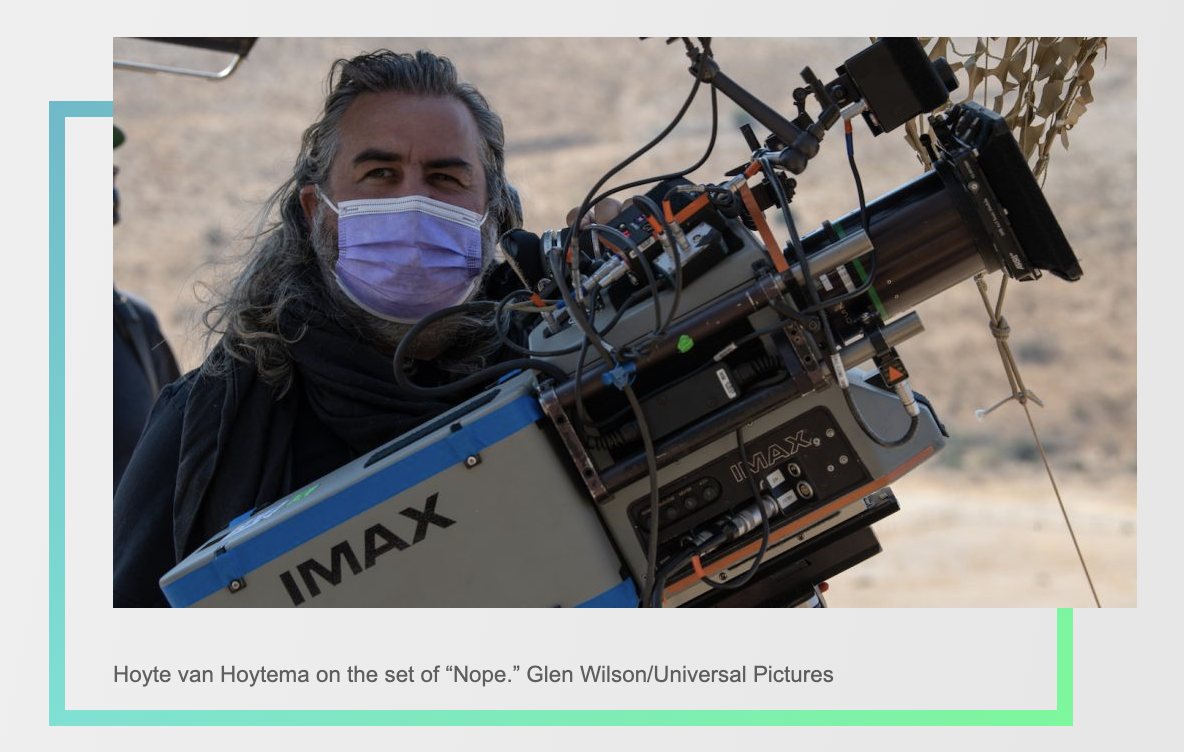

In addition to being DP, you generally serve as your own camera operator, and on Nope, you carried this shoulder-mounted IMAX camera, which looks pretty heavy. Was it difficult to handle?

I’m not stronger than any other DP. The myths around this camera are much bigger and heavier than the camera is, and it’s really quite doable. In fact, my incredible B camera operator Kristen Correll did a whole week of operating, and I saw her flying an IMAX camera on her shoulder. I live by the philosophy that as cinematographers, it’s not our job to make things convenient; it’s our job make the difficult and the inconvenient doable so that we can achieve shots that are extra special.

Changing subjects for a moment to your Oscar-nominated work on Dunkirk, there’s a remarkable sequence of British soldiers running along the beach as bombs drop around them, with you and your camera out of frame following right behind. The shot really pulls in the viewer.

It has to do with making the audience feel like they’re participating, and that automatically forces you, as the cinematographer, to be there physically. In the end, the most visceral cinema is very much about intimacy, about being in the middle of things. For me, it’s important to get in there, get closer, go further, be it and live it. Very often, that means allowing yourself to work more with your gut rather than just analyzing things in an intellectual way. But I also love moments that allow for contemplating and mood and distance.

With Nope and your other films, it seems that you move through different types of shots to create a visual dynamic?

Yes. You want a film to be immersive, but there are times when you want to take a breath – and then you get hooked by the next sequence and sucked in again. It’s similar to classical music, where a 20-minute sonata goes through all these different peaks and valleys, moments of sorrow, moments of resolve, less gas on the pedal, then you’re being pushed again. That dynamic is so important in filmmaking, going from being outside, observing, to being sucked in and becoming part of things, then being pushed out again so you can take a breath.

What techniques did you use in Nope to capture that contrast between epic wide shots and individual characters?

I worked with Panavision’s Dan Sasaki, an incredible engineer slash artist who can make whatever you need optically out of metal and glass. He designed custom lenses both for the Panavision and for the IMAX that tweak the focus so the camera can get physically closer to the faces of our actors. I want you to experience that space the same way you experience a landscape, and that’s always sort of been my obsession. Ultimately, I think faces are the most interesting things in film. I’m not so much interested in the expanse of nature if I don’t have the beautiful face to counteract it.

This article was first published on The Credits