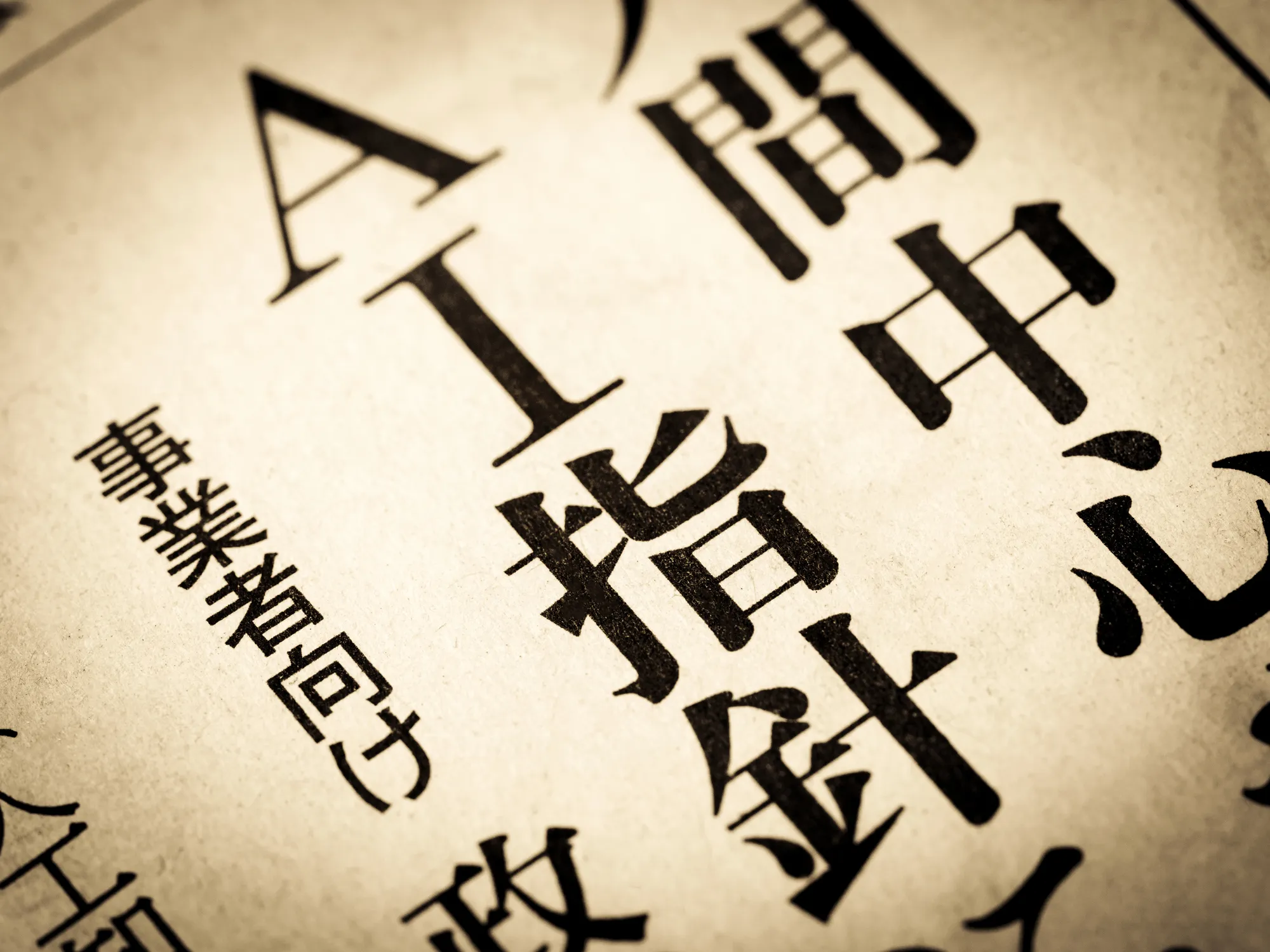

Japan has always been known for its strong creative sector and rich cultural output, from animé to manga to literature, music and film, and for its respect for intellectual property (IP) and the rights of creators. Compared to some of its neighbours in the region, it has been a pillar of respect for IP. In the middle of last year, however, this image was sharply challenged through the interpretation, or misinterpretation, of remarks made to a Diet committee by then Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (known by its acronym of MEXT), Keiko Nagaoka, with respect to Japan’s Text and Data Mining (TDM) exception. The TDM exception had been introduced in 2018. It was widely, but incorrectly, reported (for example, here and here) that the Minister had stated Japan would not enforce copyrights on data used for AI training. To the dismay of creators everywhere, this statement was pumped up by advocates for the AI industry as an example for others to follow in the competitive race to develop generative AI, even if it meant throwing rights-holders under the bus. But this is not what really happened. To clear up any confusion, Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs (ACA), an entity that is part of MEXT and which (as part of its mandate) manages the Copyright Office, has just published a draft discussion and consultation paper on AI and copyright. To understand the true situation regarding TDM for AI training in Japan, and the Japanese government’s position on this issue, read on.

The misinformation about Japan’s position on AI and copyright can be traced back to Article 30(4) of the Copyright Law, the 2018 amendment introduced to deal with text and data mining. At the time, it did not attract much attention, but has come into prominence with the explosion of data mining for AI development. This section permits the unlicensed use of copyrighted data for the purpose of testing, data analysis or data processing. Notably (and unfortunately) it does not make any explicit distinction between legally accessed and non-legally accessed materials, unlike the TDM provisions in the EU, the UK and Singapore. In other words, it does not explicitly prohibit the use of pirated content.

At first blush, Section 30 (4) appears to be the proverbial loophole in copyright protection through which you could drive the generative AI truck. That, however, is not the case despite misunderstandings regarding Minister Nagaoka’s comments. The provision carefully distinguishes between works where the end use is simply for data analysis and processing purposes, and uses where, according to the English translation of the Japanese law, there is a degree of “enjoyment” of the work by the user, in which case the exception does not apply. We will come back to the meaning of “enjoyment”, as this is a key part of the story. In addition, the use of the work must not “unreasonably prejudice the interests of the copyright owner”. Many readers will recognize this wording as the third element of the Berne Convention “three step test” that governs exceptions to copyright.

Now, let’s look at the meaning of “enjoyment” in the context of Article 30(4). Unfortunately, I don’t speak Japanese, so I don’t know what specific Japanese term is being rendered into English as “enjoyment”. The English term is likely not an exact equivalent. However, the meaning of “enjoyment” in Japanese law is critical as it is the key concept that separates a benign use of data in its most generic form from data where there is perception of, or access to, the actual content (i.e. the copyrighted expression of an idea, translated as “the thoughts and sentiments expressed in the work”). “Enjoyment” also encompasses the idea of benefit or beneficial use. One definition mentioned in the ACA’s discussion paper describes enjoyment as “the act of accepting, savoring, and enjoying something that is mentally excellent or materially beneficial”. According to the Agency’s discussion paper, if the user of the copyrighted data derives benefit from the content, such as by creating output based on that content, and thus creates “a product that allows one to directly sense the essential characteristics of the expression of the copyrighted work of the learning data…”, then “enjoyment” exists. And importantly, if enjoyment exists, the TDM exception to copyright in Article 30(4) does not apply.

Given that at least some AI generated works clearly replicate and display the essential characteristics of works they were trained on, it is clear the claim that Japan has provided a blanket copyright exception for AI training is miles off-base. This conclusion seems to have escaped those who loudly proclaimed last year that Japan had opened the taps to permissionless copying of copyrighted works for AI development purposes. The potential lack of clarity, compounded by misinterpretation of Minister Nagaoka’s remarks, has led to the drafting of the ACA discussion paper, and launch of a public consultation. It is a welcome development.

The latest draft of this paper, dated January 2024, helps clarify a number of questions related to the Article 30(4) TDM exception. The paper makes it clear that far from declaring open season on its creative sector, Japan has defined its TDM exception carefully and narrowly. However, it is not without its problems, notably the omission of any reference to a requirement for lawful access to data. Credit for pressing for clarification of Japan’s position must go to the country’s creative sector, which has worked hard to ensure that Japan’s position on a TDM exception for AI training is properly understood, both domestically and internationally.

On the lawful data issue, the discussion paper recognizes the damage that piracy causes to Japanese rights-holders;

“…the damage to Japan’s content industry caused by pirated versions is enormous, and it goes without saying that countermeasures against piracy (should be) moved forward…”.

More specifically, the paper makes it clear that knowingly collecting data from a site containing pirated content increases the likelihood that AI developers or AI service providers will bear liability for infringement, as this would represent a neglect of duty of care. This statement in the discussion paper does not, of course, have the force of law but is a further positive indication of the intent and future direction of Japanese law and regulation in this area.

Arguably, Japan’s TDM exception for AI training as expressed in Article 30(4) could have been more clearly drafted, or perhaps a more precise translation could have been prepared. The misunderstanding and reporting of Minister Nagaoka’s comments outside Japan was unfortunately distorted by cultural differences and nuances of language—not to mention probably willful distortion by those seeking to weaken copyright protection globally. The ACA’s draft discussion paper is a welcome clarification of the purpose and intent of the law, demonstrating the careful balance of interests in the legislation and reaffirming the protection that rights-holders in Japan enjoy under the Copyright Act. Hopefully, the draft paper will be finalized shortly and become the foundation for further clarification of the law’s intent.

Given the unlikelihood of further legislative change at the moment, the key conclusions of the paper could be put into officially issued guidelines or regulations. These could also include potentially incorporating all three elements of Berne’s three-step test, thus reaffirming Japan’s well-deserved reputation as a rule of law country that fully respects the rights of creators and its international obligations.

This article was first published on Hugh Stephens Blog