How long can you hold your breath underwater? One minute? Two? Maybe three? For James Cameron’s highly-anticipated Avatar: The Way of Water, now in theaters, the cast had to take lessons from free diving expert Kirk Krack in order to fluidly capture the transcendent water scenes. Why so? Bubbles.

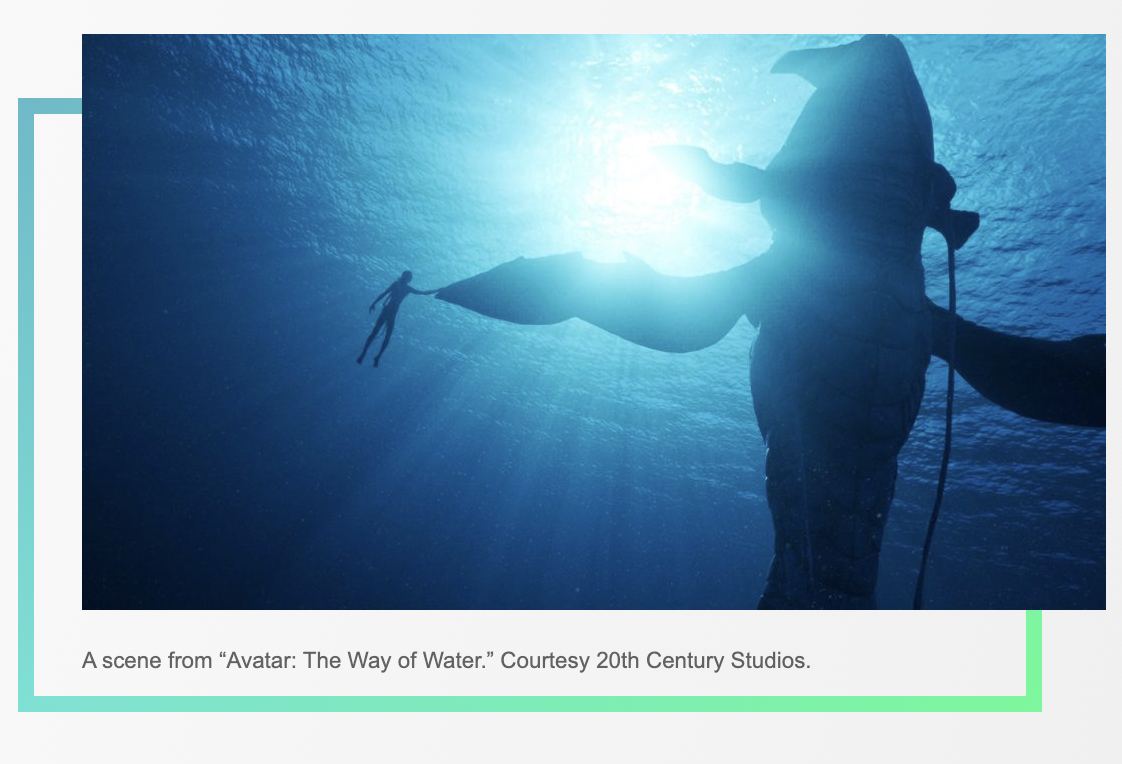

The sequel picks up from the 2009 blockbuster exploring the enchanting oceans of Pandora, in particular, the lush island reef village of the Metkayina clan, led by Ronal (Kate Winslet, who could comfortably hold her breath for 7 minutes and 20 seconds) and her husband Tonowari (Cliff Curtis). Physically, these Na’vi are different from their mainland counterparts. Their skin is more green than blue with larger hands, bigger chests, and wider tails, allowing them to effortlessly live an aquatic lifestyle. Characters swim beneath the surface or ride creatures like the long-necked ilu, the flying skimwing, and bond with whale-like tulkun.

It’s here the Sully family – Jake (Sam Worthington), Neytiri (Zoe Saldaña), and their children Neteyam (Jamie Flatters), Lo’ak (Britain Dalton), Tuk (Trinity Jo-Li Bliss) and adopted teenage daughter, Kiri (Sigourney Weaver) – seek refuge and must adapt to ocean life as “The Sky People” have returned to relentlessly hunt them down.

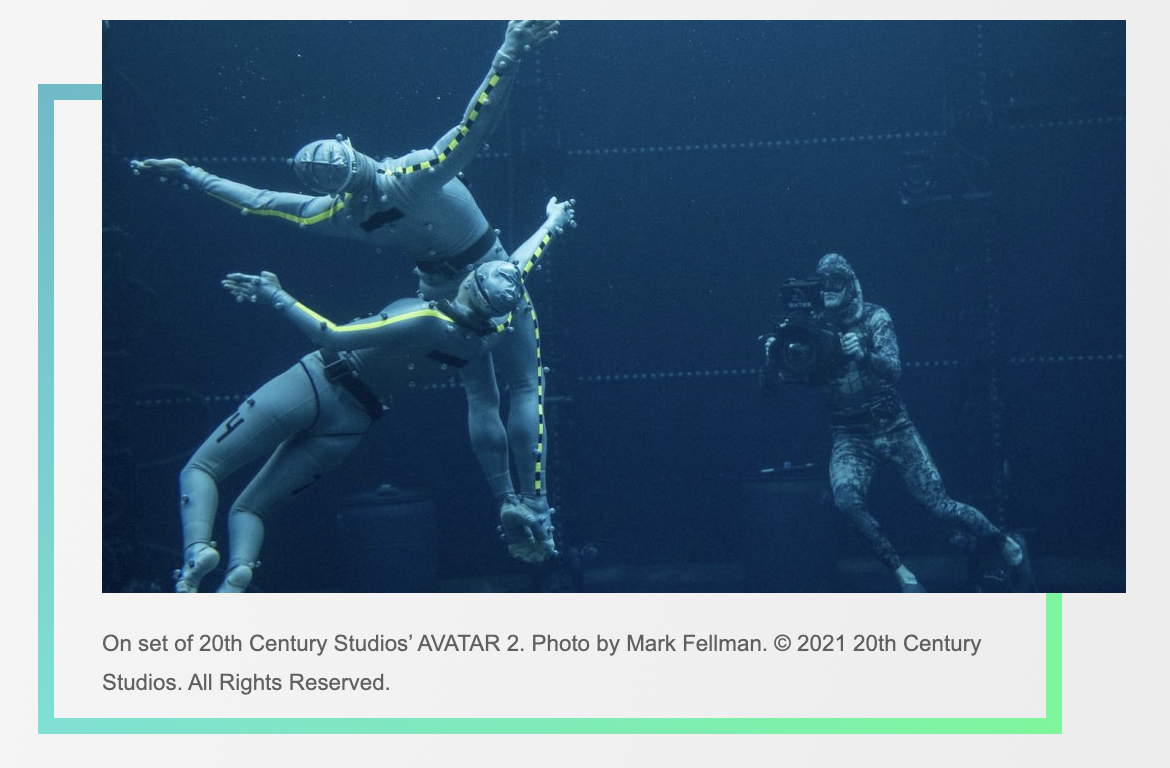

With Avatar, Cameron and the award-winning visual effect team, overseen by Joe Letteri, created motion capture technology that instantly recorded the actors’ performance while simultaneously displaying them as their Na’vi character for the director to see. But that system was designed for dry land. This time around, the hurdle was designing a water-friendly mo-cap system.

“We created two ‘volumes’,” Letteri says, who again served as senior visual effects supervisor. “There was a ‘water volume’ and an ‘air volume’ because a lot of the action happens at the surface of the water. We needed to capture above and below the surface of the water at the same time, so we created two systems and found a way to lock the two together in real-time so Jim could see the performances.”

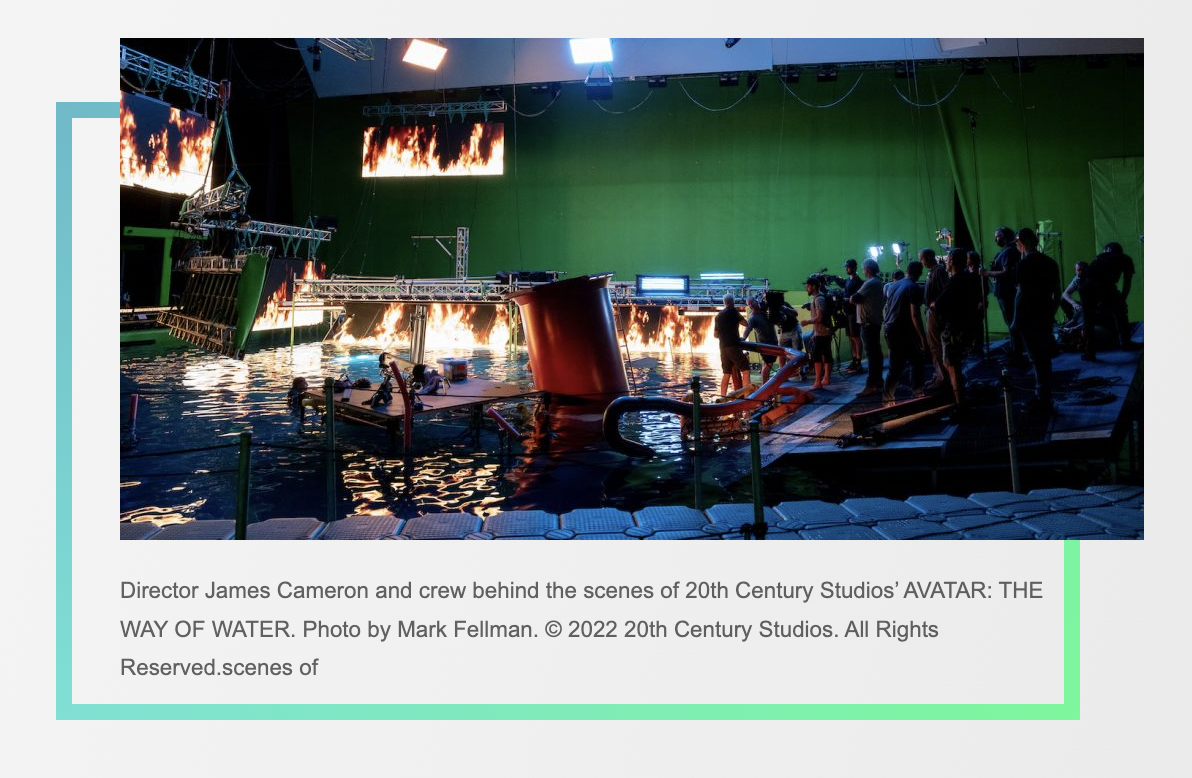

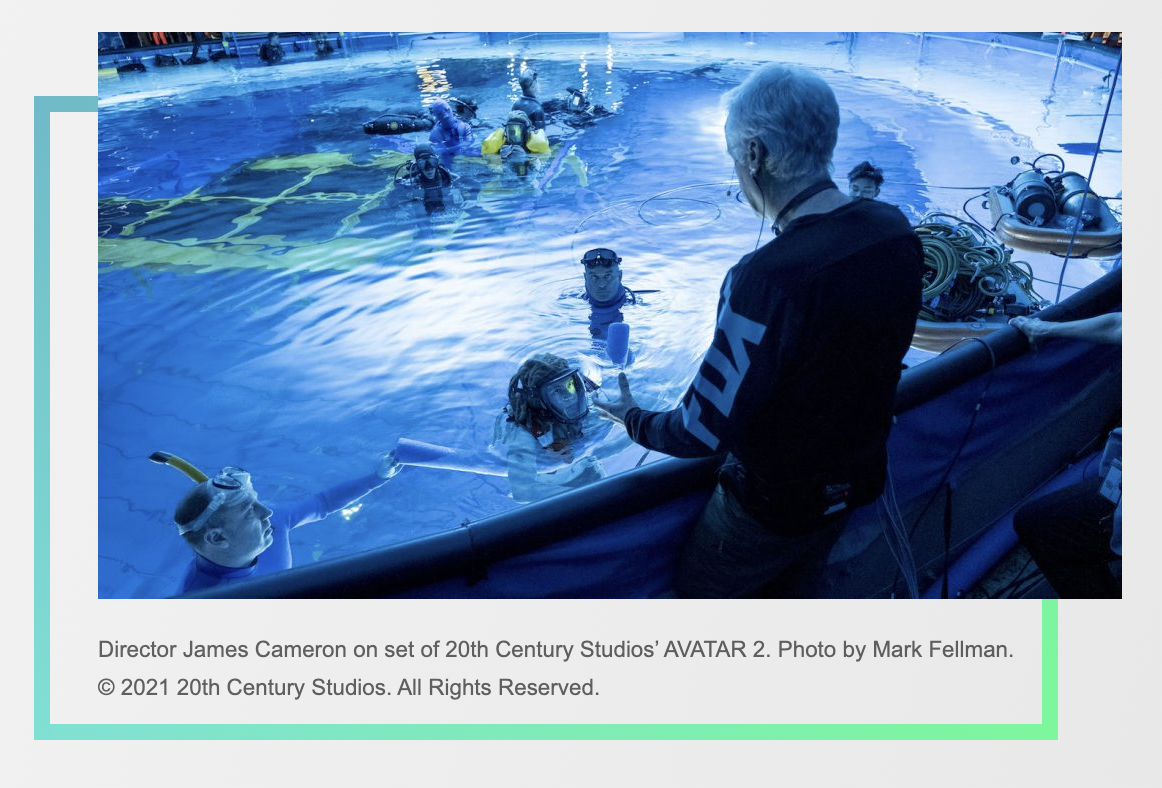

At Cameron’s Lightstorm Entertainment facility in Manhattan Beach, two tanks were built, one for training and smaller scenes and a second that stood 120 feet long, 60 feet wide, and 30 feet deep, holding more than 250,000 gallons of water. This was their “Swiss army system,” where they could simulate large waves, have characters surface, creature interactions, and create other eye-popping action sequences.

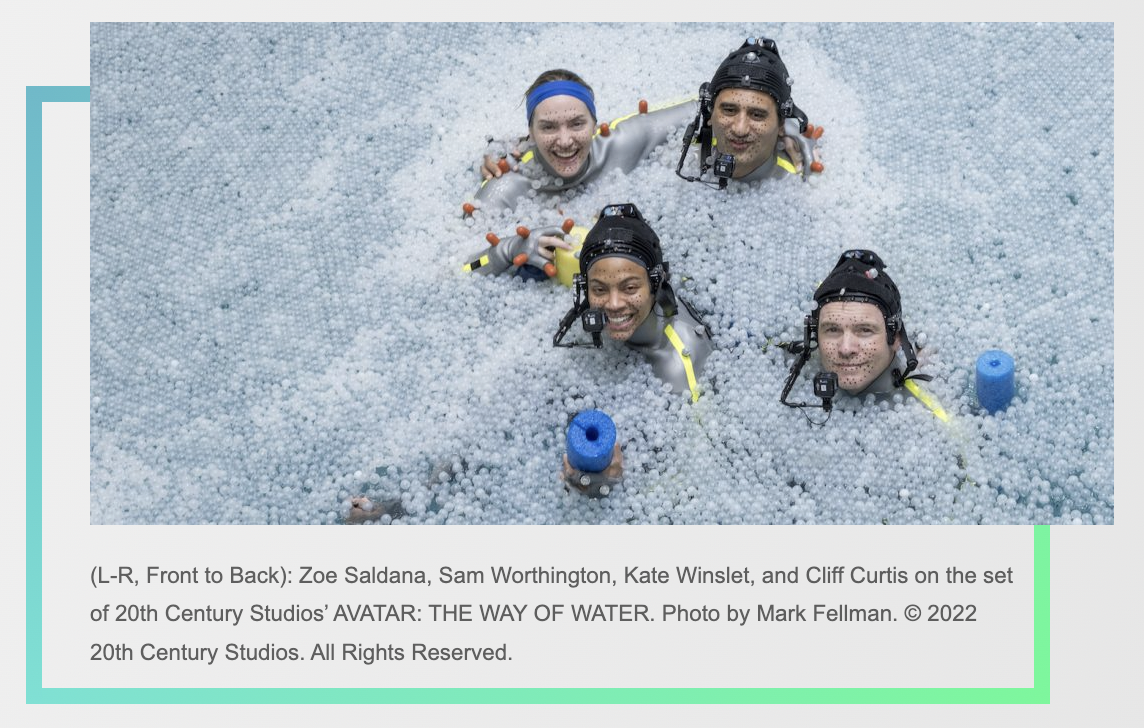

The two capture volumes, one using infrared to capture performances above the water and the other using ultraviolet light to capture everything below, were positioned one inch from each other so the data could be computed in real-time to a Virtual Camera that displayed the actors’ Na’vi counterpart. To control light reflection, hundreds of small polymer balls were placed on the surface. “This allows the surface of the water to move naturally, the actors to breathe safely and to play on the surface of the water unimpeded and uninhibited in their performance,” notes Lightstorm visual effects supervisor Richard Baneham.

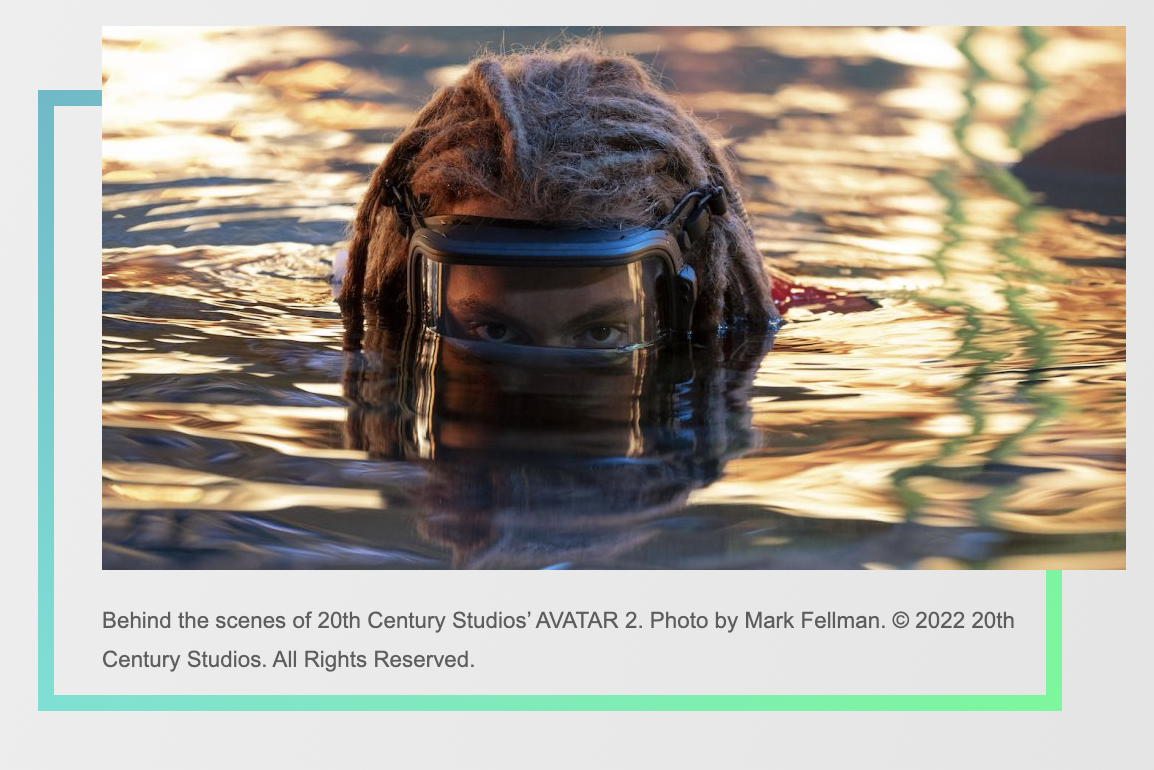

For the performance capture system to work unscathed, the water had to be clear. It meant there couldn’t be any air bubbles, not only from the actors but from anyone entering the tank. Camera operators, lighting, and safety crew all had to hold their breath. Along with additional safety procedures, safety cameras were placed to monitor those in the water.

Over 18 months, the actors’ performances were captured not only for Way of Water but for the three pending sequels, Avatar 3, 4, and 5, as all of the sequels were written prior to the start of production, allowing Cameron to shoot stories simultaneously. In capturing the water performances, Letteri says, “It really gave us the movement that you could not get any other way. There’s a shot of Tsireya [Bailey Bass] where she dives down, showing the Sully children how to swim, and they go back to the surface, and she rolls on her back and smiles at them. That’s pure performance in the water. There is no other way you could get that kind of gracefulness other than keyframing, which would take you a long time just for that one shot. This allowed the actors to express themselves in the water.”

“There is a lot of spectacle, scope, and emotion in the movie,” Baneham adds. “We really pushed the motion vocabulary bringing these characters to life. We really wanted to give the audience a sense of place.”

This article was first published on The Credits