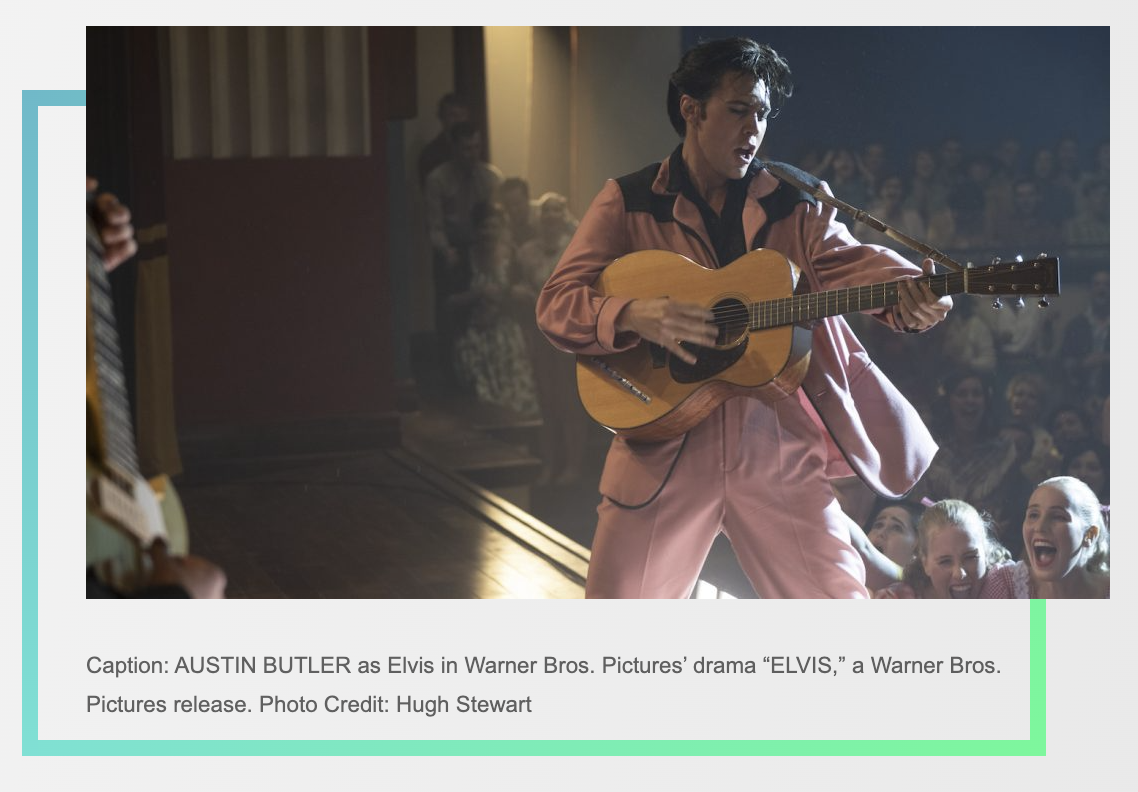

The broad strokes of Elvis’s (Austin Butler) life are all there in Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis — the precarious childhood, Army stint, loss of his beloved mother, marriage to Priscilla (Olivia DeJonge), glittering Las Vegas residency masking a perilous personal descent. But this isn’t a biopic. Rather, the director’s first feature since 2013’s The Great Gatsby is also an electrifying tale of rags to riches to ruin, this time set to a compelling score mixing the best of the King’s musical catalog with unexpected contemporary bops.

At two hours and 40 minutes, Elvis keeps with a trend for longer and longer epics from today’s marquee directors, but the pace never wanes, thanks in large part to the skill of Jonathan Redmond and Matt Villa, Luhrmann’s longtime editors (this is Redmond’s fifth project with the director and Villa’s fourth). Much of Elvis’s career highlights and musical background are explained through vigorous yet logical montages and intercut sequences that ultimately help make sense of his often self-defeating dependency on his slimy manager, “Colonel” Tom Parker (Tom Hanks, in ample prosthetics), and his eventual slide into exhaustion and drug dependency.

Villa and Redmond’s work began five years ago, collaborating with the director and the rest of his creative team to pitch the film to the studio and the actors before a script was even written, with certain sequences, like a young Elvis’s nearly religious exposure to gospel and blues, making it from storyboard to final cut pretty much intact. Other aspects were decided all under one roof on Australia’s Gold Coast, where the editing, visual effects, and music teams worked through extensive trial and error to determine which of Elvis’s catalogue best worked and where to auditorially augment key off-stage moments from his life.

“Baz always had lists of songs on his wall, some of them headed ‘how could we not include this in the film?’” Redmond says. We had the chance to speak with the editors about their long involvement with this project, restraint with archival footage, and taking the film down to its final length, no matter the difficulty.

What were some of the earliest ideas that made it through to the film’s final cut?

Redmond: One good one would be starting the movie with the song American Trilogy and Elvis collapsing on stage. That is something that just happened to be in our original pitch reel. Baz really liked it because the song is so powerful, Elvis is so incredible, and the split-screen, we did that way before that was in the script, and Baz always felt it put a smile on people’s faces and it’s an exciting place to start the film. The end as well, with Unchained Melody over it all, is something we developed very early on using the original footage of Elvis.

So you always knew you’d be editing in some original footage?

Villa: It’s peppered in there. It was always the intention to use a lot of stock footage, not necessarily of Elvis, to sort of beef up the footage that was there — the audiences, the screaming fans, the exteriors of the International Hotel, and so forth. There may be more Elvis in there than you saw.

Redmond: There are quite a few blink-and-you-miss-it moments. We aimed for a more subliminal thing than an outright cut to Elvis in the middle of the movie.

Villa: We toggled throughout the process as to whether we cared about that or not. Do we mind if the audience sees the real Elvis, or would we prefer them not to? We hedged our bets and put them in there, a little subliminally.

Redmond: Obviously part of the contract with the audience is making Austin Elvis Presley, and Austin is a force of nature, so he did a very good job of that himself. The last thing we wanted to do was confuse the audience by having too much of the real man. We didn’t want to take the audience away from Austin after the audience had signed that contract.

The editing really highlights Elvis’s increasing distress. How did you manage that?

Villa: One of the sequences we went back to time and again was what we call the burning love montage, which is when we kick it off with the wonder and aura of his touring around, and everyone’s excited by his shows, and then throughout that sequence, we see his decline. It was just a case of trial and error, but certainly, it was always in that section of the film. The marriage breakup and his shooting out TVs in his hotel room, and being with another girl, they all exist in a longer form. We were struggling with the length and had to bring it down, so condensing all those things into one montage of decline was where we ended up.

Redmond: Baz always described the International Hotel as a golden cage for Elvis, so coming back to that and giving a sense of Elvis being trapped, one of the most powerful moments for me is he’s in bed there with another girl, on the phone, and he says, can you give my little girl a hug. I always find that heartbreaking. It shows a man hitting rock bottom. As Matt said, it was a tricky sequence to put together in the time allowed, because we had full scenes there that were very powerful.

The film really gives us a sense of the stages of Elvis’s life. Did you take a consistent approach to each phase, or have different rules for different stages?

Villa: Not necessarily editorially, I don’t think. A lot of the success of that lay at the feet of Austin, who was so incredibly able to play a young man, the Hollywood years, and then an older guy. He was a joy for John and me to cut. I think the only stylistic thing we were always cognizant of for the different periods of his life was the style of montage we chose. You’ll remember when he was going on tour in the 50s, it was a montage with superimpositions and overlays and things bleeding into each other, which was very much the style of that era of filmmaking. Then you go to the 60s and there were colorful graphics whizzing around. Then we go to the 70s and there are more split screens, which was partially a 70s style but very much an Elvis style. As far as giving the film a look per period, that was probably where we concentrated our efforts. But as far as the rhythming, not necessarily.

Redmond: And to just add on, Baz was kind of aiming for 50s montages or 70s split screens, but it was always the 50s montage plus. Baz wanted to take these things into the 21st century and add his visual flair and style to these cinematic devices. So that was challenging but also a lot of fun.

Did you wind up doing a lot to prep, in terms of watching Elvis footage, his own movies, recordings of his concerts, and so on?

Redmond: When we were putting together a pitch to the studio, part of that was an audio-visual presentation, and that involved researching a lot of materials — both his concert films, obviously, his dramatic musical films, but there were also a lot of documentaries on Elvis, so doing a deep dive into that. We really spread the net very wide in our approach to the visual and musical research, which was a lot of fun. I grew up with Elvis as the cultural wallpaper of my youth. He was the King of Rock and Roll, but I didn’t know why. Digging into that was a really exciting learning curve. I had a rapid, newfound appreciation for his music.

Villa: I totally agree. I always knew Elvis more for the goofy movies and the Vegas years, but I learned a lot from this film about the impact he had on culture in general.

When it came to the final edit, it also seems like a journey through an incredible array of raw material.

Villa: I would just add that in terms of putting this film together, just the way Baz shoots, he shoots a lot of material. I’m sure John would agree that it was a monumental task putting it together. It was all great material and there’s a much longer version of this film existing. One of the big challenges — and I’d like to think we succeeded — was in bringing what was a four-hour, 20-minute assembly down to the current length. It was a shame to throw away some maybes. There were some more dramatic scenes that, as we worked our way through, were wonderful but didn’t keep on point with Elvis’s and the Colonel’s relationship with each other, so they had to go. It was a great journey, this film, because we were very much spoiled for choice in the material we had to work with.

This article was first published on The Credits