Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves is a fantasy nerd’s dream. Directors John Francis Daley and Jonathan Goldstein packed the film with human characters as colorful as the variety of creatures, both animated and practical, that populate its fantastical world. It’s a modern adventure and throwback fantasy film. Crucially, it looks terrific.

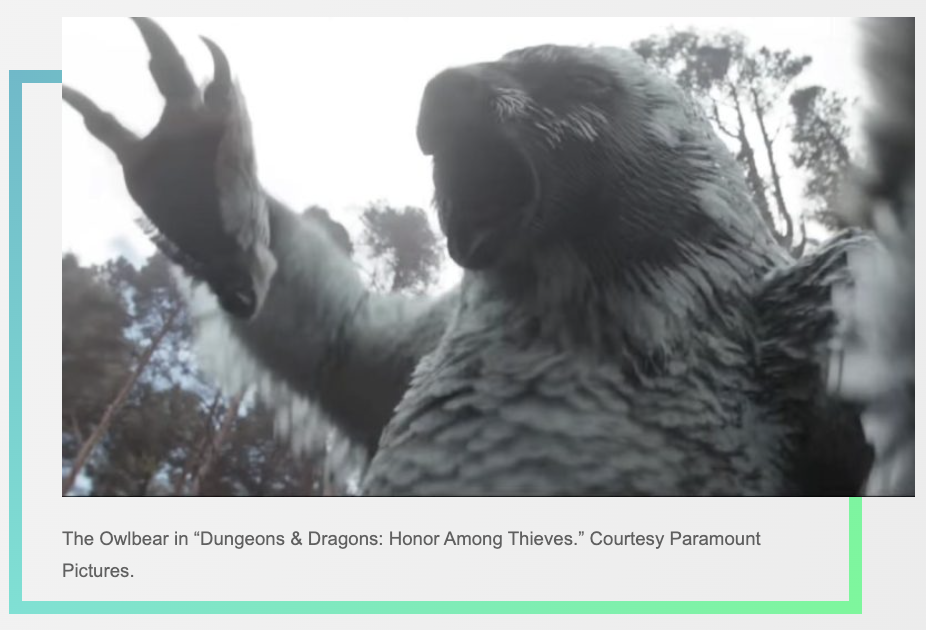

The world is tangible, thanks in part to the exceptional minds at Industrial Light & Magic. Both Ben Snow, the production VFX supervisor, and Todd Vaziri, the compositing supervisor, helped make the world of Dungeons & Dragons not only believable but gleefully playful. Look no further than the company’s work on the Owlbear – as advertised, it’s half-owl, half-bear – which the camera breathlessly tries to keep up with.

Recently, Snow and Vaziri explained how the team accomplished the Owlbear and the film’s seamless blend of digital and practical effects.

ILM did beautiful work with the Owlbear. With all the feathers, fur, and other challenges involved, how’d you get that character just right?

Todd: I would add that more than feathers, there are also wet feathers and wet fur. Particularly from a simulation point of view, there are so many points of a potential collision. With each individual feather, we have a sense in our mind of how birds move, react, and all this to simulate those to be as incredibly accurate as possible. As with almost everything with visual effects, we try to do it the physically accurate way first. When computers start exploding, and we realize our render times and simulation times are going through the roof, we have to chip away at it and figure out the best way to achieve the desired effect without, for lack of a better term, recreating an entire universe that is physically accurate.

How did you pull it off?

Todd: When two feathers intersect, there’s gonna be a lot of dynamic interactions there. They will separate, they will blend, they will merge, and they will comb away. They will then get bent and disturbed. All of those things we have to keep in mind with something like Owlbear. Usually, we don’t see creatures of that size and mass feathered. How are we going to use the feathers to our advantage to help sell the massive scale of this creature? It’s a balancing act between trying to keep something that feels real and also not breaking the bank in terms of the expense of rendering and simulations.

Beyond striving for physical accuracy with the Owlbear, how about creating a sense of personality for the creatures? What are the nuances that give it soul?

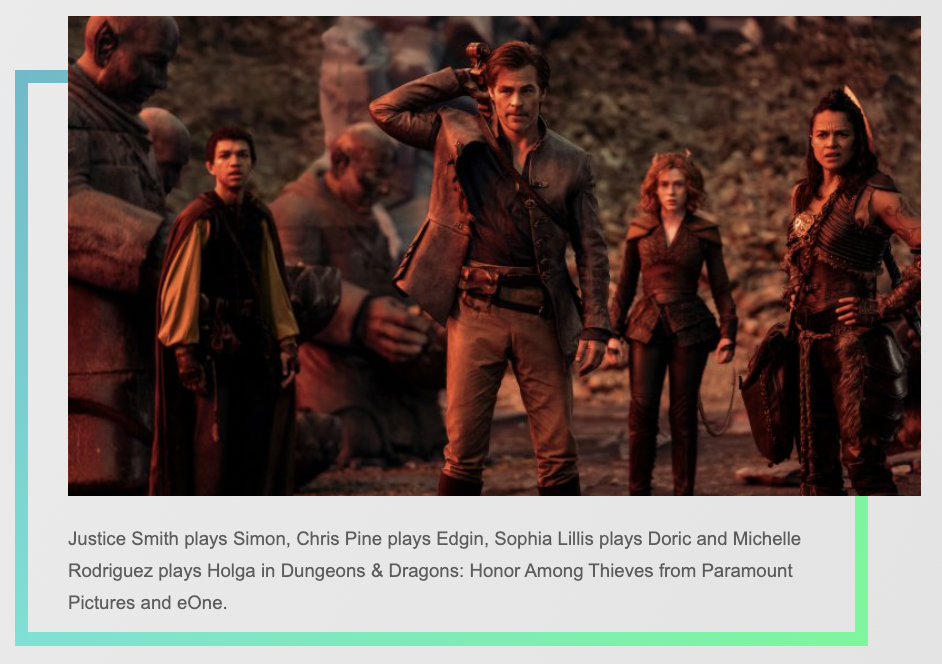

Ben: I think Kevin Martel, our animation supervisor at ILM, and the team of animators did a good job with getting that personality. It was one of the first sequences we shot because we were concerned about it. It was key that we pulled that off just to give Doric (Sophia Lillis), the shapeshifter, her due since she’s the Owlbear. Kevin Martel and [visual effects supervisor] Scott Benza did some good exploration of that fairly early as we were going along to try and get the personality right [for Doric].

Todd: I want to compliment Ben and the directors and how they designed the sequence in a way to make it feel like this is a large wild animal. There’s an element of danger there. At no point in that sequence did the camera ever go through the legs of Owlbear and arrive on the shoulder and hang out on the shoulder to be a little bit more stylized, which would’ve been better for a different movie. Here, not doing that lends a certain amount of authenticity. The way Benza and Kevin Martel designed these shots with the animation to make it feel heavy and powerful when it starts grabbing soldiers and flinging them around in its teeth, you feel the weight. It’s still dynamic, but it still feels big. The camera operator doesn’t know exactly which way that swing’s going to go. It all worked for a nice bit of spontaneity to the sequence as opposed to being super stylized.

Were there practical stunts mixed into that sequence?

Ben: We shot some practical stunts as well. I know we replaced at least one of those. Did we use a lot of the practicals?

Todd: It goes back-to-back from a CG soldier to the stunt performers and then enhances their performance. If the Owlbear was supposed to smack one of the stunt people, who were then pulled back on wires, we accelerated a few frames at the very beginning to give it that extra energy.

There’s such a strong balance between practical and digital effects in this movie. Legacy did wonderful work with the puppets and practical creatures. How closely did Legacy and ILM collaborate?

Ben: We’ve worked with Shane Mahan and the Legacy team on a bunch of films going back decades, like Iron Man and Galaxy Quest. It was a great collaboration with them because, in addition to doing the practical effects, they did a lot of work on the creature design as well, even if they were going to be computer graphics. For example, they did the corpses in the graveyard sequence. Shane would come up and say, “Look, we’re going to do this. The guy’s got a nose, but can you help us get rid of the nose?”

The practical effects make the visual effects that much more effective, then?

Ben: I think the balance is interesting because the directors leaned into the practical effects. We were gonna go back in and do a bit of post-correction on some bits, just to manipulate the faces maybe to match the ADR or the dialogue better. But in the end, the directors leaned into it a little bit, feeling that it worked with our aesthetic, much like it does in a Star Wars film when they have a practical creature. The audience seems to enjoy that, and certainly, the actors enjoyed having that tangible thing on set. I really like the blend because it keeps the audience guessing, how did they do this or that?

Todd: Especially a movie like this where it has a twinkle in its eye. It’s leaning into the fantasy aspect. Again, with the Owlbear or something, we still tried to design the sequence so that there was spontaneity. With the practical creatures or people on set, it allows for improvisation, and it allows for spontaneity.

What’s your relationship with imperfections in digital effects? As you said, Ben, the directors wanted to preserve some of those happy accidents or imperfections you easily could’ve perfected, so is it always a case-by-case basis?

Ben: My definite desire is for the audience not to be questioning the visual effects. We can fix virtually anything in post. John Francis Daley and Jonathan Goldstein were terrific in this regard, in that if there was a problem that was due to the photography, then they’d say, “Oh, what’s this thing here?” For example, if it turns out to be a slight lens flare, we would pull up the take and say, “Oh, it was from here on the plate.” They would say, “Good, then keep it.” There’s a certain language that we, as viewers, get used to with filmmaking, warts and all, which I think is good.

Todd: We’re always striving for plausibility and believability, like Ben said, to sell the fact these events are happening in front of a camera. We’ve developed a cinematic vocabulary over a hundred years of filmmaking. The audience can’t particularly articulate why they believe something was photographed in front of a camera. Sometimes, particularly with computer graphics, we strive for clinical perfection. There’s something about us that’s, like, we need to make this perfect from a clinical point of view. In all of filmmaking, there is no perfection. Some high-quality images and sequences flow together, but some things happen in movies that are imperfect. It’s the happy accidents, the things that we all understand as a filmed piece of art. They need to be considered as part of the filmmaking process. It’s all in service of telling the story, so the audience can absorb what the characters are going through and feel the emotions and the momentum of a scene.

This article was first published on The Credits