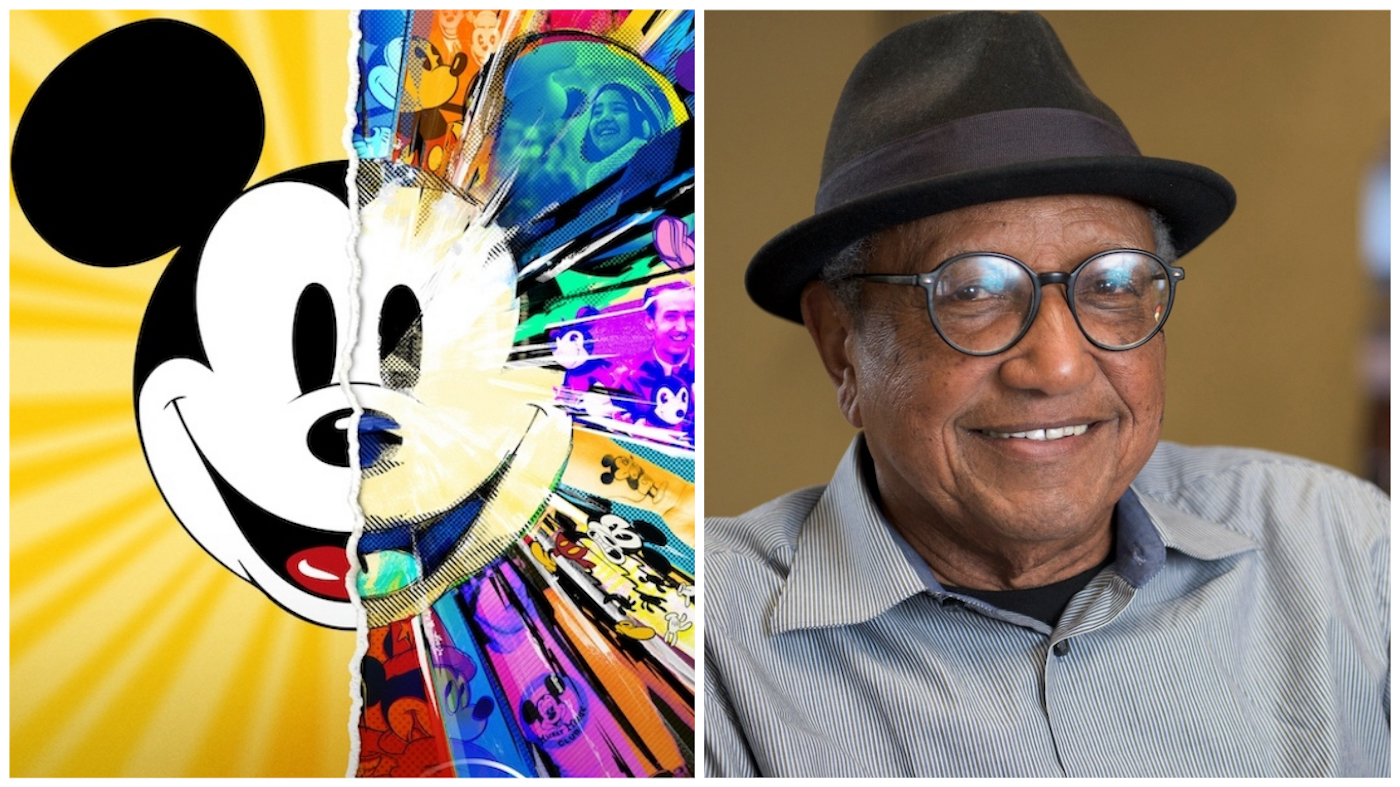

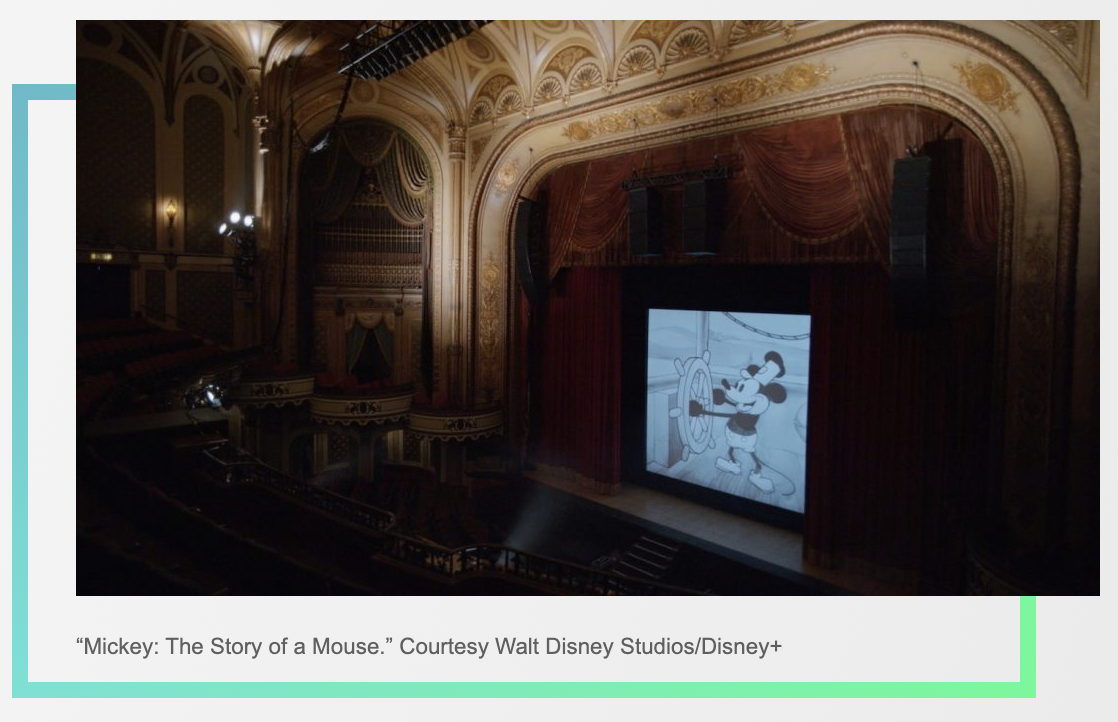

As Walt Disney once famously said, “It all started with a mouse.” Steamboat Willie, which starred a mouse that became an icon, was released on November 18th, 1928. To commemorate the anniversary of that historic short, Disney+ is airing a new documentary called Mickey: The Story of a Mouse, which examines the character’s continued cultural significance in the US and around the world.

What makes this documentary so fascinating is it not only considers the evolution of Mickey through his nearly a hundred years in existence, but it also highlights traditional animators, both those working inside the studio now and those influential to Mickey’s progression from the early days of Disney. The documentary follows a new short being made, Mickey in a Minute, created with 2D animation by three traditional animators still working inside the studio. Mickey: The Story of a Mouse director Jeff Malmberg doesn’t shy away from considering the darker aspects of Mickey’s history and the character’s influence on counterculture, which gives the film more heft than you might expect from a studio that’s filming a documentary about its own legendary icon on its own streaming platform, Disney+.

“Disney Legend” and longtime Disney employee Floyd Norman is perhaps the only interviewee who knew Walt personally. Norman worked at the studio starting in the 50s and became the first Black artist to remain at Disney on a long-term basis. He started as an in-betweener on 1959’s Sleeping Beauty, was a story artist on 1967’s The Jungle Book, spent over a decade working on Mickey Mouse comic strips and went on to contribute to the Pixar story department on Toy Story 2 and Monsters Inc. The Credits spoke to Floyd Norman about the documentary and about how Disney’s iconic and beloved character impacted his life and career.

What do you remember of Mickey Mouse as a child? I know Bambi and Dumbo are what inspired you to want to work for Disney, but how did Mickey figure into all of that?

Mickey was a big part of my life as a kid, mainly because I loved reading Mickey Mouse comic books. I don’t know why, but for some reason, those adventure stories in the comics were the thing that really got me as a child. I absolutely fell in love with them. On quiet summer afternoons, I would sit in the backseat of my father’s car with my stack of Mickey Mouse comic books and just read of these amazing adventures that the mouse would take us on, never knowing that one day I would be able to craft my own set of Mickey Mouse adventures, years and years in the future. That was my introduction to Mickey, and then consequently, he became a big part of my life and career.

When you started working for Disney in 1956, you briefly worked on a Mickey short at that time. It had to be for The Mickey Mouse Club.

Yes. There were a number of things going on in the 1950s at Disney. Disney had just made the move into network television, so we had the weekly Disneyland show on ABC, plus a daily Mickey Mouse Club on ABC television. In a sense, you might say Mickey Mouse was pulled out of retirement because The Mickey Mouse Club on television put Mickey back center stage, and of course, there was that famous song. He had everybody singing it, from little kids to us soldiers marching and singing in formation. We did that as well when I was in the military, believe it or not. We were all marching and singing The Mickey Mouse Club song. It was just part of our culture and in all of us. We all grew up watching Mickey Mouse, and he stayed with us into adulthood.

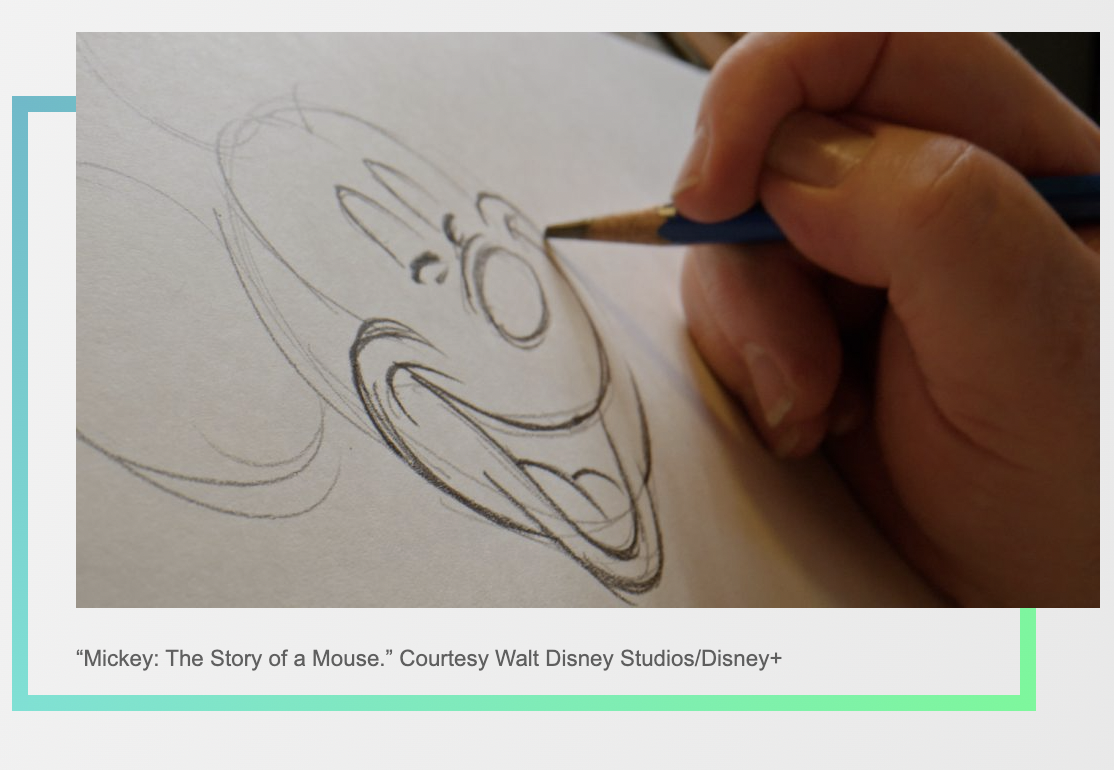

You’ve worked on both traditionally animated and CGI films. There are only a few 2d animators working inside Disney Animation, but the studio started a 2D hand-drawn trainee program in 2022. Why do you think 2D animation is so important to the Disney legacy going forward?

Well, that’s what it’s all about, the Disney legacy. The Walt Disney Studio is built on the foundation of traditional hand-drawn animation. Mickey Mouse honestly looks his best as a hand-drawn character. Not that Mickey cannot be animated in CGI, he can be, and the computer can do amazing things, but when you get right down to the emotional resonance of a character like Mickey Mouse, that really needs to be done the old-fashioned way, with pencil and paper. It’s almost as though the animator’s spirit flows from his hand, through his pencil, onto the paper. The animator truly brings life to the drawn character. That doesn’t happen with CGI because you have the computer interface that kind of gets in the way, but there’s a purity, a simplicity about hand-drawn animation. That’s why Mickey Mouse is best realized as a hand-drawn character. I think he’ll always be animated most effectively if he’s hand drawn.

In the documentary, you see Mark Henn, Randy Haycock, and Eric Goldberg working on the new short and how they’re capturing the spirit of all the eras of Mickey. You can really see through his entire history how important 2D is to his character.

It’s really interesting, having been on the front lines myself as an animator when you put that blank sheet of paper on your drawing board, that’s what you’re starting with, an empty sheet. There is literally nothing on the paper until you put pencil to paper, and so that creation, that drawing, flows out of the artist through the pencil onto the paper, and you give that drawing life. Those men and women who can do that and do it well are to be highly regarded because it is a very difficult task. It may look simple and easy, but it involves so much, everything from draftsmanship to performance, to design, to all the things that take the flat, dead pencil drawing and gives it the magic of life. That’s some pretty heavy stuff when you think about it.

You scripted the Mickey Mouse comic strip for years. You took him from the Ozzie Nelson figure he’d become, and you made him an Indiana Jones-type adventurer you remembered from your childhood comic books. What were some of the guiding forces for you in that work?

In a sense, we were somewhat handicapped by the Mickey Mouse that was in the comics at that time. I inherited Mickey Mouse from the original artist and writer Floyd Gottfredson. What had happened is, as happens to all of us, Floyd Gottfredson had gotten older. He had been with the studio since the 1930s, and as Floyd grew older, Mickey grew older along with him. So consequently, the Mickey Mouse that I inherited was honestly, as you said, more like Ozzie Nelson, less like Indiana Jones, and I wanted to bring Mickey back to the young, dynamic, vital, energetic Mickey Mouse that I grew up with. I wanted to inject more life back into Mickey, and after begging and pleading with the syndicate, as well as with the studio bosses at Disney, they allowed me to go back and write Mickey Mouse as an adventure comic and no longer the stay-at-home dad hanging around the house, giving advice to the nephews. I was able to get Mickey out of the house, put him back on the road, take him down to wherever the next adventure would lead and create an energetic, dynamic Mickey Mouse once again. I think Indiana Jones is a good role model, and Mickey Mouse was Indiana Jones before Indiana Jones.

The documentary talks about a point in history when Mickey sort of splits into two, traditional Mickey and counterculture Mickey. Why is it so essential to allow cultural and pop interpretations of the character?

You know why? Because Mickey represents all of us. No one group. No one nation. In terms of spirit, nobody owns Mickey. We all own Mickey. We’re all part of Mickey. He represents us, no matter who we happen to be. I think that’s part of the magic of Mickey, that he’s one of us. He’s our best friend, our best buddy; he’s there to help us when we need a helping hand. He’s there to inspire us. He’s there to remind us that there are good things worth doing and that life is worth living. Mickey is the ultimate optimist, much like Walt Disney was the ultimate optimist, seeing the good in everything and being enthusiastic and energized by the promise of a glorious future. It sounds corny, but Walt Disney said he loved corny, so Mickey Mouse is corny, but so was Walt.

This story was first published on The Credits