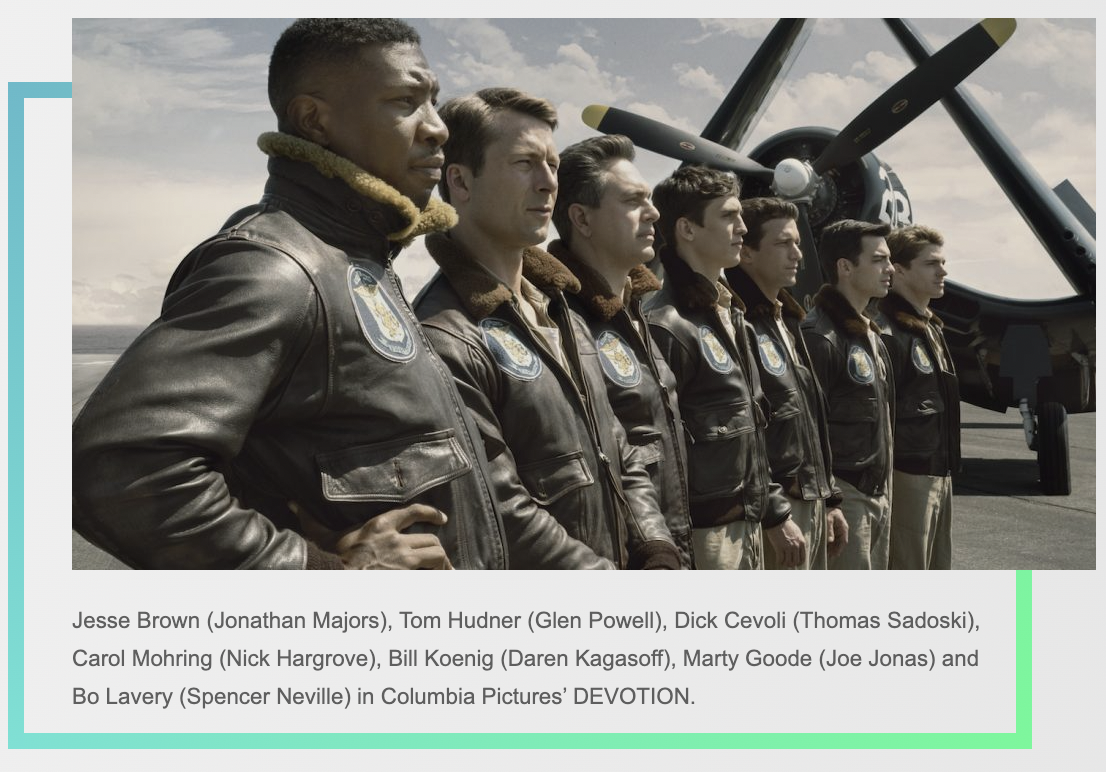

The new historic war epic Devotion is based on the bestselling book by Adam Makos of the same name. The true story centers on the first Black aviator in Navy history, Jesse Brown (played by Jonathan Majors), and his fellow fighter pilot Tom Hudner (Glen Powell, who also acts as producer on the film), and their heroic actions during the Korean War.

Director J.D. Dillard, who helms this exciting and emotional film, was better known as a genre filmmaker focused on horror before joining Devotion. He grew up the son of a Naval aviator, with his father Bruce Dillard becoming only the second African American to fly with the Navy’s Blue Angels, so Dillard jumped at the chance to tell a story that resonated with him from his own family history. He hired a number of talented Black creatives below the line, including famed production designer Wynn Thomas, the first African American production designer in the history of American film.

The Credits spoke to Dillard about his collaboration with Thomas, working with his dad as a consultant on the film, and those dramatic dog fighting scenes in vintage airplanes.

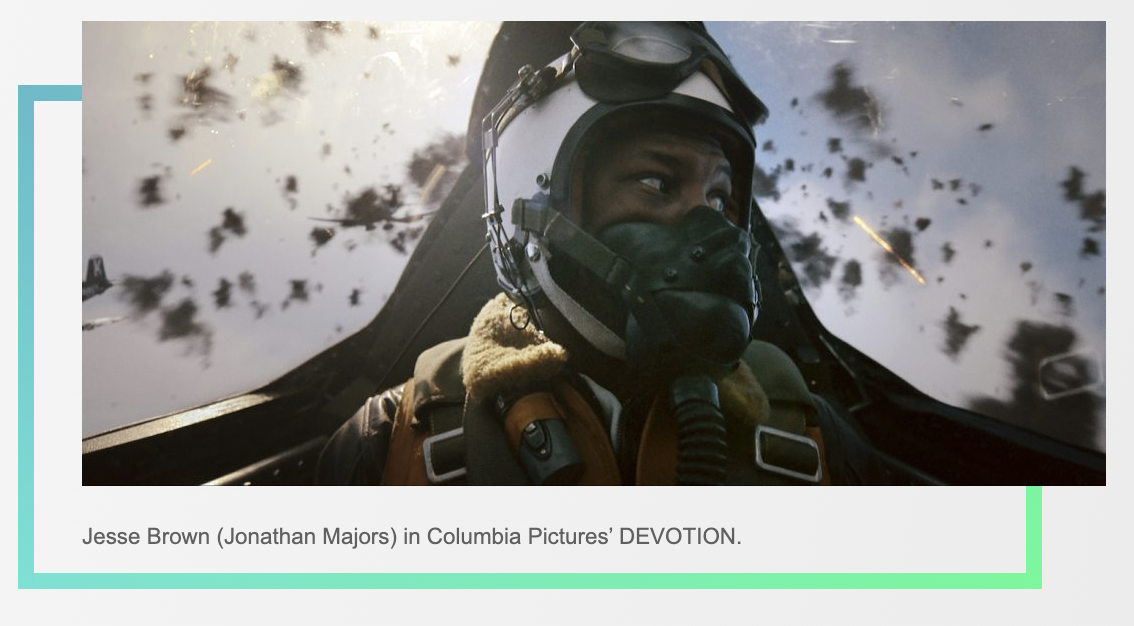

Can you talk about the technical aspects of filming both the aerial footage of the airplanes on missions and filming inside the cockpit with the pilots?

All the aerial work was shot in camera, and that was a laborious but very fun process, sourcing all of these warbirds from across the US, getting them painted to be in the same squadron, getting them to the same location, and then starting with pre-vis, and building out what some of these scenes were going to look and feel like, one shot at a time. It was taking them up into the sky with Kevin LaRosa and his team and checking off the shots on our shortlist. It sounds easier when I just say it like that, but it involves a gigantic team and a lot of planning to pull that off.

And inside the cockpit?

Then inside the cockpit, there were two approaches. The first aviation scene in the movie is in the Bearcat, and I wanted to make sure that we took that as an opportunity to introduce the audience to aviation, so we shot the cockpit parts of that scene a little differently, where we put Jonathan and Glen in the backseat of a two-seater, filled the cockpit with cameras, and then play that scene actually from the sky. That gave us a really healthy reference point about how we were going to build, once we came into the war section, and all the boys were in the Corsairs, how all of that was going to look and feel. What we did there was we built a set design piece of cockpit, and we played the scene in front of the LED volume, which is super hip these days, but we shot all of these background plates for real, put our guys in the cockpit, and played it in front of the background plates. In a weird way, even though you still need visual effects to put more planes in the background and exploding flak, when you’re sitting there at a monitor it still gave you a fully in-camera aesthetic, because your foreground element is real, your background element is real, and the cameras are in the cockpit with the boys. Those were the two big approaches for all of our aerial work.

The first Black pilot that flew with the Blue Angels was Donnie Cochran in 1985. And then your dad, Bruce Dillard, was the second, in 1989. Your dad spent time on the production with you. What were the most useful and powerful lessons he offered that had an impact on the finished film?

You know, it’s funny, I feel like when I tell folks that my dad was a consultant on the film, they assume that all of my questions were about protocol and how to salute, what the language is in the cockpit, and speaking to your wingman. While all of that is true, where he was most helpful, and I think where his imprint is most on the film, is actually asking about the quieter moments. It was asking him really how it felt and how the conversation went down when he told my mom he was going on his first cruise. If he was in a bad headspace or upset about something, where would he go on the ship to just find quiet? It was during those moments, the emotional reality of being a Black aviator, that his feedback and insight were really bespoke to this movie.

What was your collaboration like with cinematographer Wynn Thomas? He was breaking barriers around the same time as Donnie and your dad. How did you work together to mesh his aesthetic with what you wanted as director?

Wynn is such a wizard in that he will fight to preserve the heartbeat of the film at every level of production detail. His very specific attention to detail, his emotional specificity that he has in his work is really, to me, one of the things that makes Devotion feel rich. I think his process fit Devotion very well because he pulls a lot of real-life reference. He finds books that have been out of print forever that just give such a specific look into the world that we’re exploring. It was actually intensely immersive. You go to Wynn’s office, and it’s just filled with things that you did not even know existed from the period, just as a means to get you into that headspace. The other thing about Wynn is that he’s just a legend. There’s always this paradox, I feel, as a director, where everyone on your set has made more movies than you, but it’s in collaborators like Wynn. That’s exactly what puts the wind in your sails because he has such a body of work.

Can you use an example of a scene or environment that speaks to who he is as a production designer?

I’ll use two, and they’re very different. One is the reading room on the ship. It’s the room where the boys all get their orders and hang out in between missions. You would think he would just look at a couple of pictures and put it together, but when I stepped into that room for the first time, I was really taken by not just how immersive it was but how worn in it was, how lived in it was. The one thing about making a military film is that you do have lots of references, but with Wynn, it was the difference between “this looks like the picture” and “I feel like I walked into the picture.” That’s everything from the details on the CO’s desk to the chairs. Wynn was able to actually get them from one of the ships that is still period-accurate that currently acts as a museum. We got all of those chairs on loan. You actually were walking into the picture because those chairs are in the picture. That’s just one example that’s very small and specific.

And the other?

On a bigger scale, it was turning River Street in Savannah into the French Riviera, and the vision it took to pull that off, and the flexibility I was given to be able to look in each and every direction when filming. We were wholly in France and could certainly be nowhere further from, so it’s in both the big and small. It was incredible to watch Wynn sort of conjure a reality.

This is obviously a very special movie for you. How has the film changed you as a filmmaker?

I think I can split that answer into two halves. On the one, I’m not accustomed to this amount of responsibility, in terms of being a guest in other people’s real-life legacy, and it’s certainly not something anyone in the production took lightly. When you’re writing a creature feature, and you want to switch it up, you don’t need to ask anybody. You don’t need to worry. Being predominantly a genre filmmaker, it’s a whole other set of circumstances. I have been so incredibly grateful to join this story for a moment, but with that comes an enormous sense of clarity and pride. You could feel it on our set, from grips to gaffers, all the way up and down the cast and crew; everybody had read the book because of the journey we were on. When you feel that level of synergy, you start to feel it’s bigger than a movie. The other thing that I grew and learned and felt on this movie is going forward, everything has to feel like this. This movie reset the bar for even just my own emotional connection to the material. It has to feel like this, and that should be agnostic to genre or true story. Working on a movie takes years, and I don’t think I could survive working on one thing for that long if it didn’t feel the way I felt working on Devotion.

This article was first published on The Credits