Recently, India passed the long-awaited Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. The internet is abuzz with discussion on the Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023 which became the Act after being passed by both houses. For example, see Internet Freedom Foundation’s first read of the 2023 bill, Hindu paywalled piece calling this “An Act to cement digital authoritarianism,” WIRE piece presenting five Pitfalls to Watch Out for in the Data Protection Law, RTI activists’ alleging that the Bill would Severely Restrict Scope of RTI Act. There are also several LinkedIn posts underscoring some nice points to ponder upon, for instance, see among others, the posts of Sriya Sirdhar. There is also news claiming that “Governments abroad look to model on India’s ‘landmark’ data law.” Those interested in the topic should check these Five Must Reads on the issue.

Amidst the mixed reception that the Act has received, what intrigued me the most was the amendment to Section 8(1)(j) of the Right to Information (RTI) Act, 2005 which seems to have diluted the essence of it. In this post, I highlight some of those concerns. Read NCPRI’s statement in this regard.

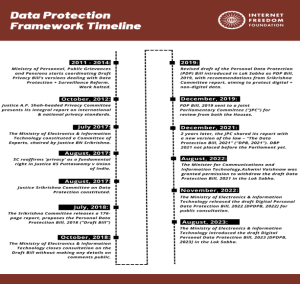

Before I delve further, take a look at the useful chart provided by the Internet Freedom Foundation. This will help us comprehend why this Act is long-awaited. Each stage that led to the formulation of the current act (supposedly) holds importance in shaping its present text. However, it seems that earlier expert opinions and reports on this topic especially w.r.t. Right to Information were not adequately considered. (See also) In this post, I underscore this inconsistency.

Source: – https://internetfreedom.in/iffs-first-read-of-the-draft-digital-personal-data-protection-bill-2023/

For quick reference of readers, as per Section 44(3) of the 2023 Act, Section 8(1)(j) of the RTI Act should be substituted by:— “(j) information which relates to personal information”. This means that there would be no obligation to give any citizen information which relates to personal information. What this does, however, is substantially dilute the RTI Act as the current text of Section 8(1)(j) of the RTI Act 2005 does not provide an oversimplistic and blanket exemption to disclose personal information but keeps a check of public interest.

The below table explains the change better:

| Unamended Section 8(1)(j) | Amended Section 8(1)(j) |

| Notwithstanding anything contained in this Act, there shall be no obligation to give any citizen … “information which relates to personal information the disclosure of which has no relationship to any public activity or interest, or which would cause unwarranted invasion of the privacy of the individual unless the Central Public Information Officer or the State Public Information Officer or the appellate authority, as the case may be, is satisfied that the larger public interest justifies the disclosure of such information:

Provided that the information which cannot be denied to the Parliament or a State Legislature shall not be denied to any person.” | Notwithstanding anything contained in this Act, there shall be no obligation to give any citizen …

information which relates to personal information. |

Reading the unamended provision, it is clear that it was not so generic and broad as the current wording “information which relates to personal information”. Instead, it laid down a set of factors that were to be considered while denying information, bringing an extra layer of checks and accountability while denying information. Appositely, it required that the information sought has no relationship to any public activity or public interest; it would not cause an unwarranted invasion of privacy; it can be disclosed if the Public Information Officer is satisfied that there is a larger public interest that justifies its disclosure. The 2023 Act seeks to remove all these checks in one stroke.

This amendment clearly contrasts the A.P Committee Report on Privacy which noted that “Section 8 of the Act lists specific types of information that are exempted from public disclosure in order to protect privacy. In this way privacy is the narrow exception to the right to information. When contested, the Information Commissioners will use a public interest test to determine whether the individual’s right to privacy should be trumped by the public’s right to information.” It went on to say that “The Privacy Act should clarify that … disclosure of information as required by the Right to Information Act should not constitute an infringement of Privacy.”

Tellingly, the 2023 Act does exactly the opposite through its Section 38(2) by noting “ In the event of any conflict between a provision of this Act and a provision of any other law for the time being in force, the provision of this Act shall prevail to the extent of such conflict.”

Relevantly, Chapter 7 of Justice B.N. Srikrishna’s Committee report delves into the issue of the relationship between data protection/privacy and the right to information in detail from Pages 102 – 105. Recommending a balancing or proportionality test, it noted that “The fact that information is in the custody of a public authority gives rise to a presumption that it is information available to a citizen to access. The burden then falls upon the public authority to justify denial of information under one of the exceptions. This is a critical feature of the design of the RTI Act and the Committee finds that this must be preserved notwithstanding a data protection law.”

Relevantly, the Committee proposed an amendment to the very Section 8(1)(j) but with a divergent approach. The proposed provision had three key components:

“First, nothing contained in the data protection bill will apply to the disclosure under this section [8(1)(j)]. This is to prevent privacy from becoming a stonewalling tactic to hinder transparency.

Second, the default provision is that the information which is sought must be disclosed. It is assumed that such disclosure promotes public interest and the common good of transparency and accountability.

Third, only if such information is likely to cause harm to a data principal and such harm outweighs the aforementioned public interest, can the information be exempted from disclosure.

The Committee finds that such a formulation offers a more precise balancing test in reconciling the two rights and upholding the spirit of the RTI Act without compromising the intent of the data protection bill.”

However, the 2023 Act seems to have again disregarded the suggestions of the committee and experts. I think, this disregard or under-regard of transparency aspect also stems from the fact that privacy is a now a fundamental right which it was not so earlier. See Prashant Reddy’s potent pieces here and here to know more about this.

Shailesh Gandhi, a former Central Information Commissioner, penned a potent piece in this regard titled “Ten instances show how the digital data protection bill will undermine the RTI” highlighting 10 real-life instances where the Right to Information had a substantial impact. However, due to recent amendments, those instances may no longer happen in the future. I reproduce some of them from his list which gives an inkling of how appalling the new amendment is.

Among others, Gandhi illustrates the case of Deen Dayal Hospital in Delhi, where activist Dinesh Kaushik, in 2010, requested information about patients admitted to the hospital and their provision of free treatment. The underlying context here is that private hospitals receive substantial concessions on land with the stipulation that they offer free treatment to approximately 20% of financially disadvantaged patients. The information brought to light that this obligation was not effectively fulfilled.

Similarly, Gandhi mentions the case of activist Anand Bhandare in Mumbai who appraises the performance of corporators seeking information about their fund utilization, attendance records, and overall performance through the RTI Act.

Another intriguing instance pertains to President Pratibha Patil. In 2012, retired Colonel Suresh Patil noticed that an expansive plot of land in Pune was assigned for Ms. Patil, who was to retire in the same year, and an extensive mansion was being constructed. Using the RTI Act, Mr. Patil sought information regarding the post-retirement residence she was entitled to. The response revealed that the proposed retirement home for the President greatly exceeded her entitlement. Subsequent to the ensuing controversy, the project was eventually abandoned.

Another example, not from Gandhi’s list though, is of CIC Directing the Prime Minister’s Office to reveal information on private persons who accompanied PM Modi on foreign trips. This was a request from Neeraj Sharma, who sought the “list of CEOs of private business, owners or partners, private business officials, etc. who accompanied Prime Minister Narendra Modi to international visits”. The information was not revealed at the end but vaguely responded.

Interestingly, after the recent amendment, there would not be any ground for asking for any such information which appears to be, even remotely, dealing with “private information” on the face. Some potential impact of this can be, as Gandhi argued in his recent piece, rejection of details of – Member of the Legislative Assembly funds, the beneficiaries of the Prime Minister’s fund, contestable caste and education certificates, ghost employees, account of disproportionate assets compared to declared income, verification of affidavits of elected representatives, unfair assessment of students and job seekers in government, charges of against officials.

This article was first published on IPRMENTLAW