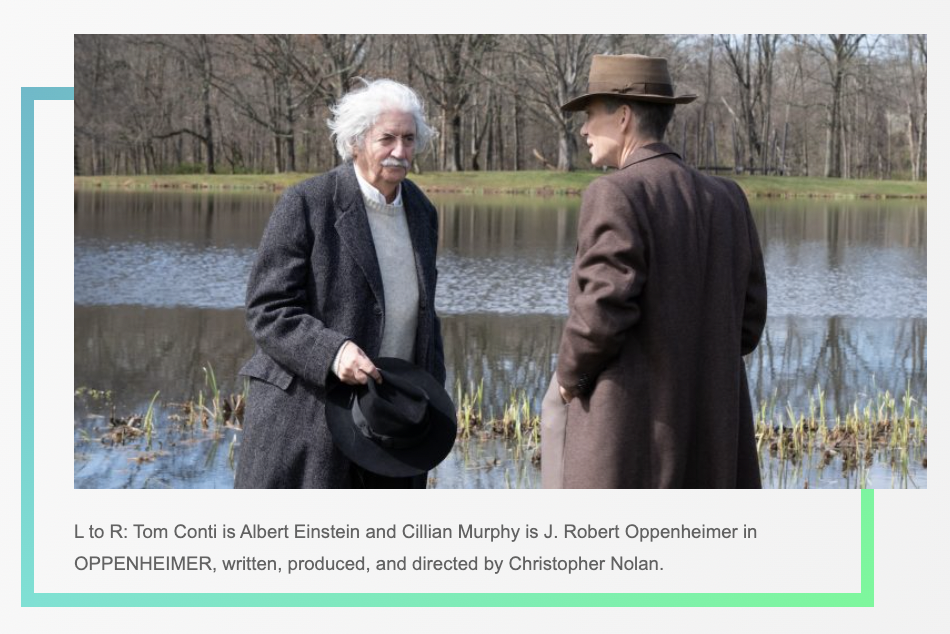

Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) stares wide-eyed into the pond spread out in front of him; his last conversation with Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) on the potential catalytic effects of the atomic bomb has rendered him speechless. The music swells as the screen fades to black — the final scene of Christopher Nolan’s highly-anticipated Oppenheimer.

A “singularly dramatic moment in history” — That’s how Nolan describes the motivation behind his desire in telling the story of Robert Oppenheimer.

“This moment in which Oppenheimer [and] the key scientists in the Manhattan Project realized they could not completely eliminate the possibility of the chain reaction from the first atomic detonation, that first test that would destroy the world,” Nolan says.

It was that specific moment in history, Oppenheimer’s reckoning with the possible world-ending consequences of his actions, that guided Nolan’s storytelling.

“His story is one of the most dramatic ever encounters, full of all kinds of twists, and suspense, things that you couldn’t possibly deal with in any kind of fictional context,” he explains. “So I really got hooked on the idea of trying to bring the audience into his experience…what he went through, make his decisions with him…try and arrive at a telling of his story that would invite understanding rather than judgment.”

Moral ambiguity is a theme Nolan frequently explores in his films, and Oppenheimer tackles that tenfold. But Nolan says he’s not here to tell us whether or not Robert Oppenheimer was a good person but rather to walk the audience through his decision-making.

“Humans, individual flaws, and the tension between his aspirations and his brilliant intellect telling him what he should be doing, and his inability to live up to those things, or his blindness to where some of these things might take him,” Nolan explains of his creative process. “That’s what creates interesting tension in the story.”

When stripped raw, Oppenheimer, at its core, is a story with an age-old message: If you play with fire, you’re going to get burned. And it tells us as much in the opening shot: billowing flames, hundreds of feet high, encompass the entirety of the screen, the words of the great story of Prometheus overlaying the fire.

“We haven’t made a documentary; we’ve made a dramatic interpretation of his life,” Nolan says. “You’re looking at a character who was very careful. But everything he said about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—it was very precise, never apologized. He never acknowledged any guilt as relating to his part and what had happened. And yet, all of his actions from 1945 onwards are the actions of somebody truly suffering under an immense weight of shame and guilt.”

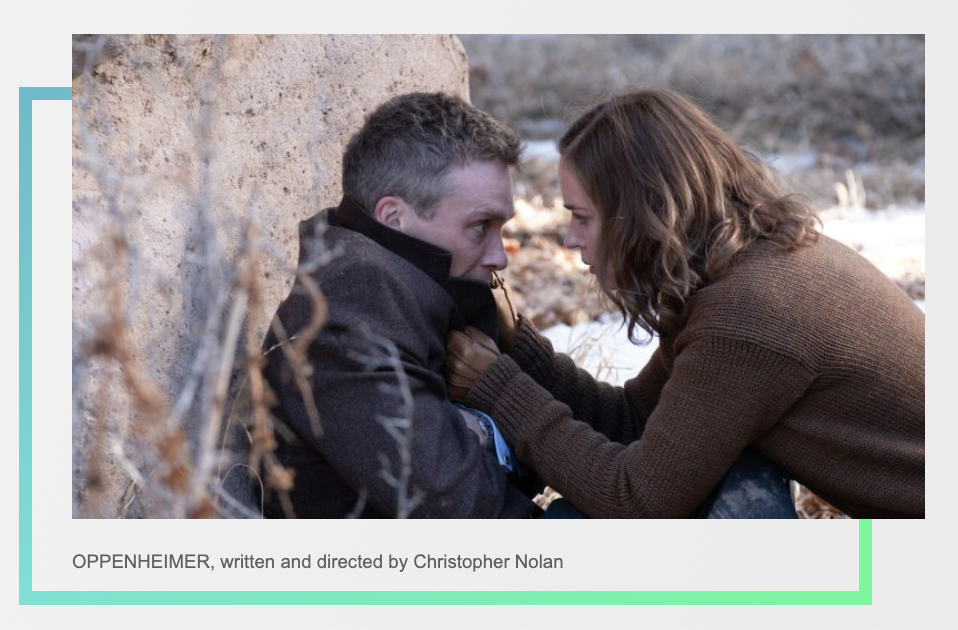

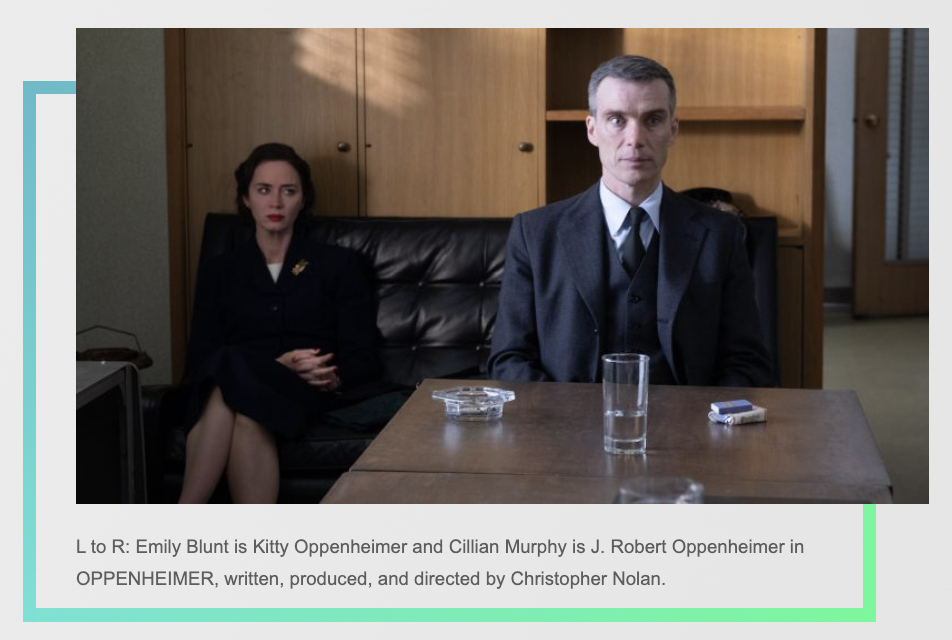

After Hiroshima and the death of Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), there’s a scene in the film where Oppenheimer is slumped against the trunk of a tree, spiraling into an all-consuming panic. Kitty Oppenheimer (Emily Blunt) shakes her husband and says, “You don’t get to sin and then play the victim.”

Nolan doesn’t confirm his personal feelings on Oppenheimer’s morality, and when asked if this scene is meant as an interpretation of Kitty’s feelings in that part of her life or an interpretation of the audience’s feelings toward the character, he says it’s all of the above.

“There are times when the writing wants to synchronize with or guide the audience’s particular expectations or interpretations,” he explains. “But I think what’s most successful is when it synchronizes sort of seamlessly with the feelings and emotions of the character in the moment.”

Oppenheimer is immensely detailed — an attribute characteristic of Nolan’s filmmaking style, along with intricately woven storylines. No apple goes unnoticed, no close-up without intent. In Oppenheimer, it’s the hanging of bed sheets on the clothesline to dry that become one of the most profound metaphors in the film and serves as an almost unspoken language between Robert and Kitty.

“I came across this fact in the book, this notion that because [Robert] couldn’t talk directly to anybody about the success or failure of the test, they came up with this code relating to change in his life,” Nolan explains. [Oppenheimer was based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer” by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin.] “The sheets make up a bit. And I wanted to bring it together in a visual sense. For me, Kitty Oppenheimer is one of the most interesting characters in the film—one of the most interesting characters of Oppenheimer’s real-life story—their relationship was complex. So I love the idea of a coded message between them that only they can understand.”

Kitty Oppenheimer was a brilliant scientist in her own right, and Nolan says that during her time at Los Alamos (the creation town of the atomic bomb), she was “given very little to do,” so the sheets also symbolize her domestic experience.

“It was very frustrating [for her] and caused a lot of problems,” he says. “So, for me, it was the coming together of all of those different things.”

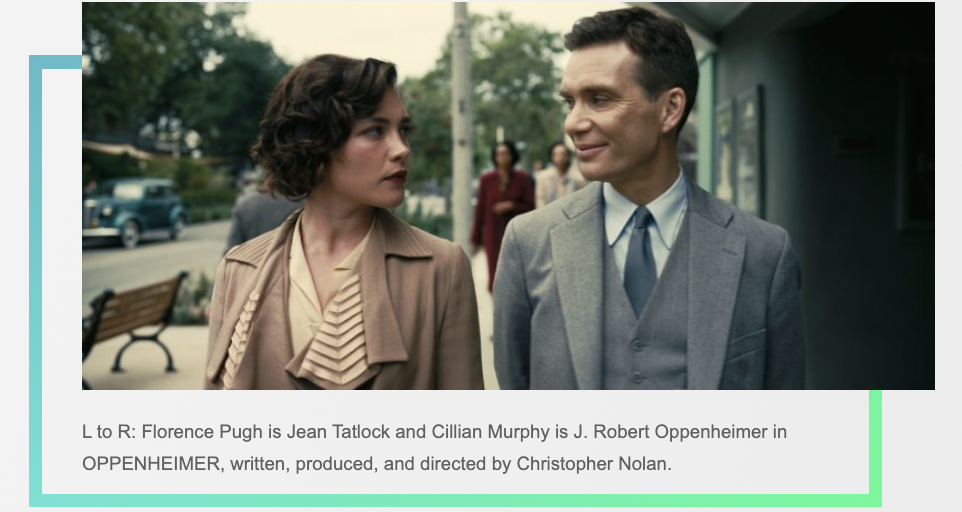

During his 32-year marriage to Kitty, Robert Oppenheimer had a long history of affairs, a fact not left out of Nolan’s retelling. One of Oppenheimer’s most famous lines in history is when he quoted part of the Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” after witnessing the first detonation of the atomic bomb. In Nolan’s version, that line comes during a sex scene with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh).

“I wanted to destabilize the context in which that quote normally appears,” he says. “Oppenheimer was very controlling of his image in his public statements. He was extremely self-conscious, very, very aware of the theatricality of his persona, and used that to further a lot of causes he espoused, the things he was worried about. And I wanted to present this in a new way that would cut through that.”

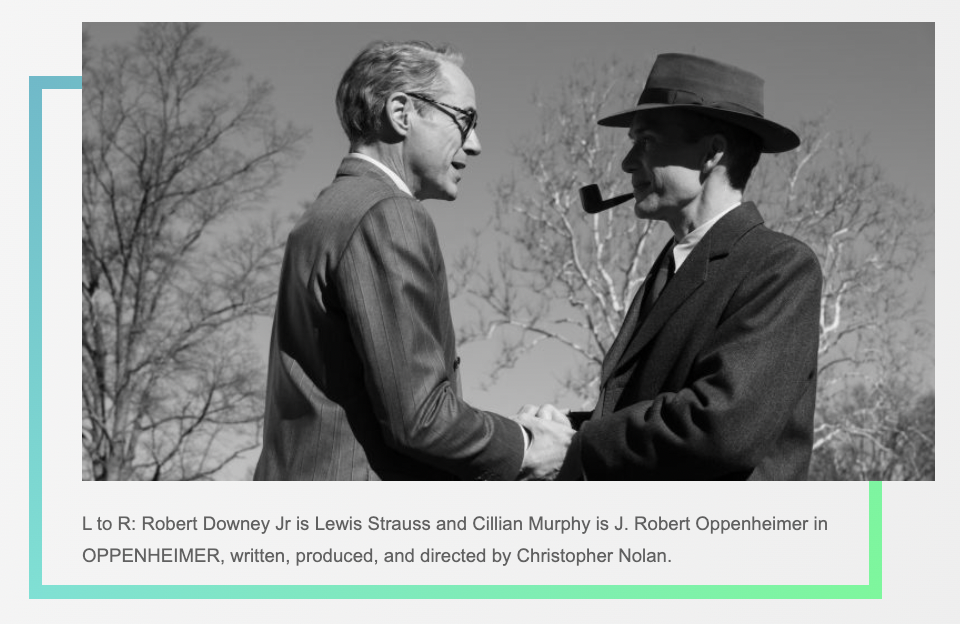

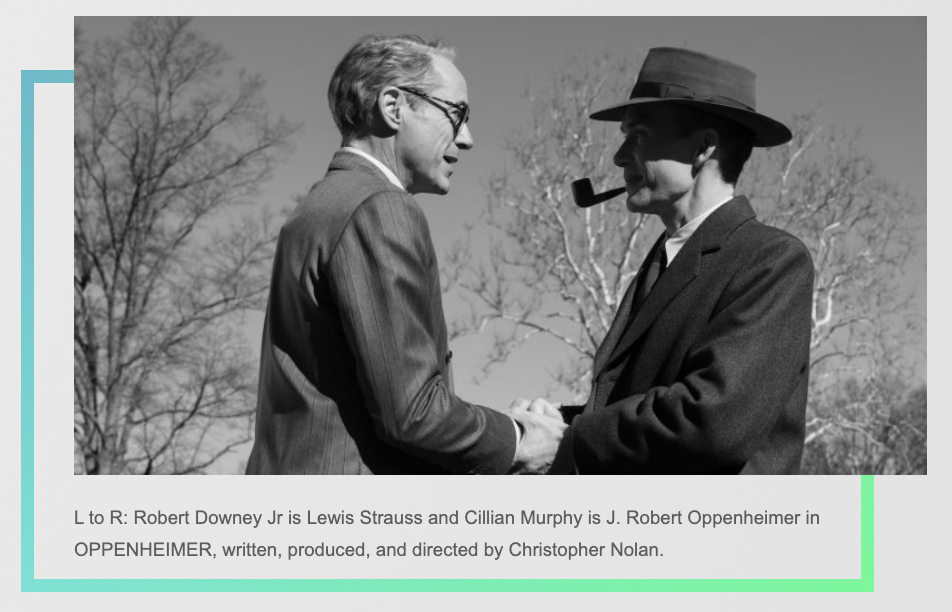

Like many of Nolan’s films, Oppenheimer shuffles between past and present — between the creation of the atomic bomb and the two security hearings beginning in 1954 about Oppenheimer’s affiliation with the Communist party. Beyond the use of black-and-white scenes to depict the timeline of the hearing, Nolan says the color shifts serve another purpose.

“You’re looking for a subtle way, a clearer way of shifting between the intensely subjective storytelling in the cover sequences,” Nolan explains. “And then the more objective view very often provided by Robert Downey Jr., as his character, Lewis Strauss.”

hh

hh

This article was first published on The Credits