She designed Paul Thomas Anderson’s flashback to 1970s-era L.A. in Licorice Pizza and shaped the fifties look inhabited by Marilyn Monroe in Blonde. Now, production designer Florencia Martin takes viewers back to 1920s Hollywood in Oscar-winning writer/director Damien Chazelle’s Babylon, which immerses Margot Robbie’s Nellie LaRoy and Brad Pitt’s Jack Conrad in the gloriously decadent early days of silent film. Chazelle, a stickler for authenticity, shot at Old Hollywood locations, including Busby Berkeley’s former home, and worked with Martin and her team to construct an old-time “Poverty Row” movie studio in the middle of the desert using lumber hammered together with nails because the Phillips screw had not yet been invented.

“Babylon‘s a love letter to filmmakers,” says Martin. “You see the craft and feel the spirit of people who just wanted to create something.” Speaking from her Los Angeles home alongside a vintage 1949 movie poster advertising James Cagney in White Heat, Martin talks to The Credits about the art of the “jewel box” movie backdrop, vintage cameras, and the “castle in the sky” featured in Babylon‘s outrageous party sequence.

Judging from your White Heat poster, you’re into Hollywood history. Did Damien have you study old movies so you could wrap your head around the vibe from that era?

We looked at a lot of silent-era movies and also relied on the archives at Paramount Studios to see how old movie sets operated. The early Poverty Row studios were built right on the dirt. There’s this beautiful photo of Charlie Chaplin sitting in a chair with an umbrella surrounded by dusty film equipment, and all you see is dirt and orange groves behind him. Damien wanted audiences to feel immersed in what early Hollywood productions really looked like.

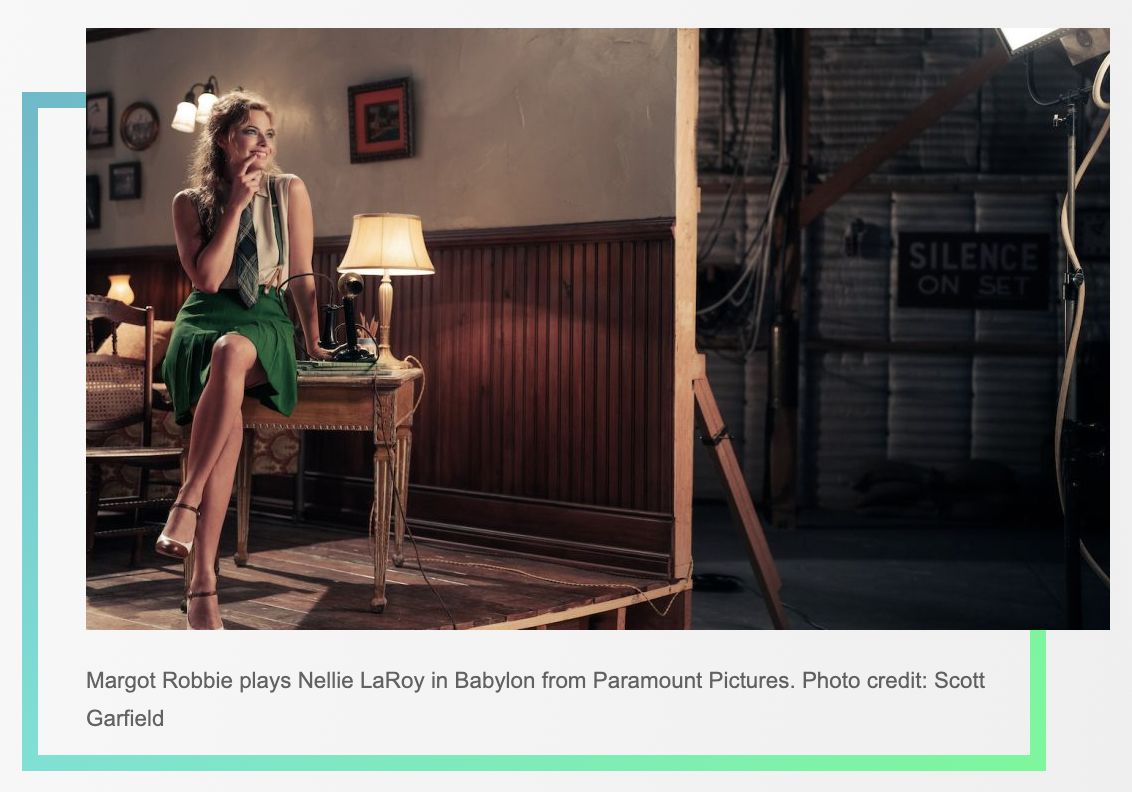

Margot Robbie’s character Nellie shows up for her first day of shooting at the fictional Kinoscope Studios, a noisy, chaotic environment where several movies are being shot simultaneously. What were you aiming to convey there?

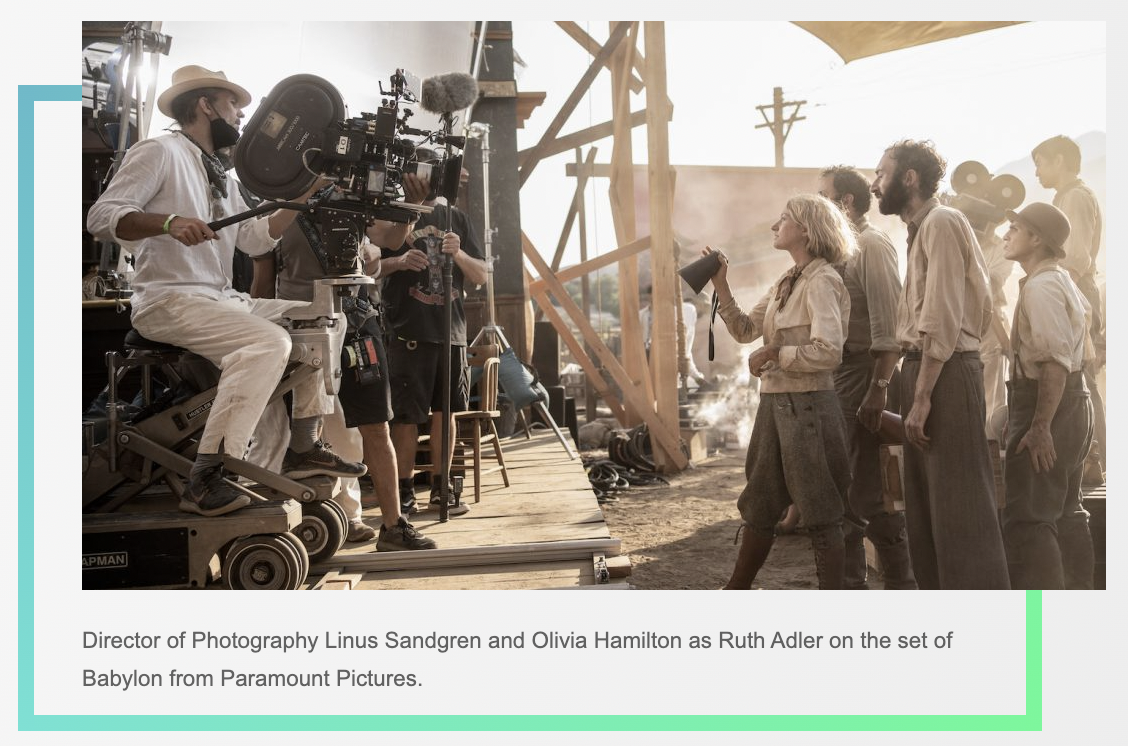

We wanted to capture this ragtag kaleidoscope of sets and the kinetic cacophony that was happening. Because they weren’t recording sounds, silent filmmakers used live music to set the tempo for the camera moves and the actors. At the same time, we look over the hills at a Hollywood movie ranch where they’re staging this huge MGM battlefield epic starring Brad Pitt’s character Jack. You see cameras getting trampled on by horses and the mayhem of picture cars crashing into the towers. I remember standing at the top of a hill with our DP Linus Sandgren months before production started, looking out at this amazing ranch, seeing where the sun was going to land, and saying, “This is the spot.”

Not unlike filmmakers from the twenties, you constructed your own “Poverty Row” studio in the desert outside of L.A.?

Yes. We were driving around looking for a location for the battlefield when we saw some old barns on the side of the road. “Pull over; let’s go.” We went up and over a hill and saw this amazing stretch of land on a ranch surrounded by mountains and orange groves reminiscent of what we’d seen in those early Hollywood photographs. As a team, we decided this is where we’re going to build Kinoscope from the ground up.

The construction of this Poverty Row studio took about six weeks. How did you pull it off?

I had an amazing construction coordinator, Mike Diersing, and more than 160 craftsmen, art directors, set designers, illustrators, and graphic designers — everyone came together. We used digital models and constructed our road coming in, we put in light poles and our main front gate, which was inspired by Dorothea Lange’s [Depression-era] photos. We wanted people to build dreams in the most inhospitable, barren locations. You don’t think of that [environment] going hand in hand with what Damien called our little jewel boxes.

These “jewel boxes” being the movie set backdrops lined up in a row, one after another?

That’s right. We painted backdrops for a jungle warrior scene, a kitchen on fire scene inspired by Fatty Arbuckle’s film The Cook, and an “oriental” backdrop shot against a pink backdrop. Then we go into the Gold Rush western bar for Nellie’s scene, with snow made from asbestos, which was true to the times. It was funny to show these big bags of asbestos being lugged over the shoulders of these crew members and then used to put out the fire for the kitchen scene.

Babylon later transitions to the early days of talkies. It’s fascinating to see this clunky first-generation technology being used in situations where everybody seems to be making it up as they go. What was involved in replicating the process for making old-time talkies?

We did a lot of research to depict that early technology, which included this very rag-tag camera box. When talkies came along, cameras had gone from being hand-cranked to being motorized.

And these motorized cameras made noise that could be picked up by the microphones, right?

Yeah, they hadn’t yet gotten to the idea of covering the camera, so instead, they covered the operator and the entire camera in a box.

Were you able to secure vintage equipment from the period?

Oh my gosh, yes. Our set decorator Anthony Carlino and our prop master Gay Perello worked very closely with this local prop shop called History For Hire. They have a collection of old cameras that were re-furbished, so in the film, when you see close-ups of the 2709 camera, that’s from the Prop Shop. It felt great to get that layer of authenticity happening in real-time with cameras and microphones that were actually used in the twenties.

Where did you shoot those early talkies?

They were all shot at Paramount [Pictures] Studios. We prepped out of the Clara Bow building [named after the silent film star]. Our wonderful costume designer Mary Zophers prepped out of the Edith Head building [named after the eight-time Oscar-winning costume designer]. So much history there! We transformed three soundstages into the twenties, which meant quilting over the modern signage and the bright yellow safety equipment.

Babylon opens with a bang, taking the audience inside the mansion of movie mogul Don Wallach, who’s hosting a huge, raucous party. How did you put together that space?

That opening sequence is stitched together from eight different locations and built settings. We’d found an image of Beverly Hills in 1926, which shows this barren road with one palm tree and a little Ford Model T. We go through three roads taking you to Don Wallach’s castle in the sky because we wanted to show the audience what it looked like to be driving through Bel Air and the Hollywood Hills toward these mansions. Wallach decided to build a Gothic castle reminiscent of the mansions built by power players like Hearst and [oil tycoon Edward L.] Doheny. His mansion was shot at a castle built in 1926 by the real estate developer of Hancock Park, an hour away from Los Angeles. We built an extension in front of the garage to serve as the entrance to the ballroom.

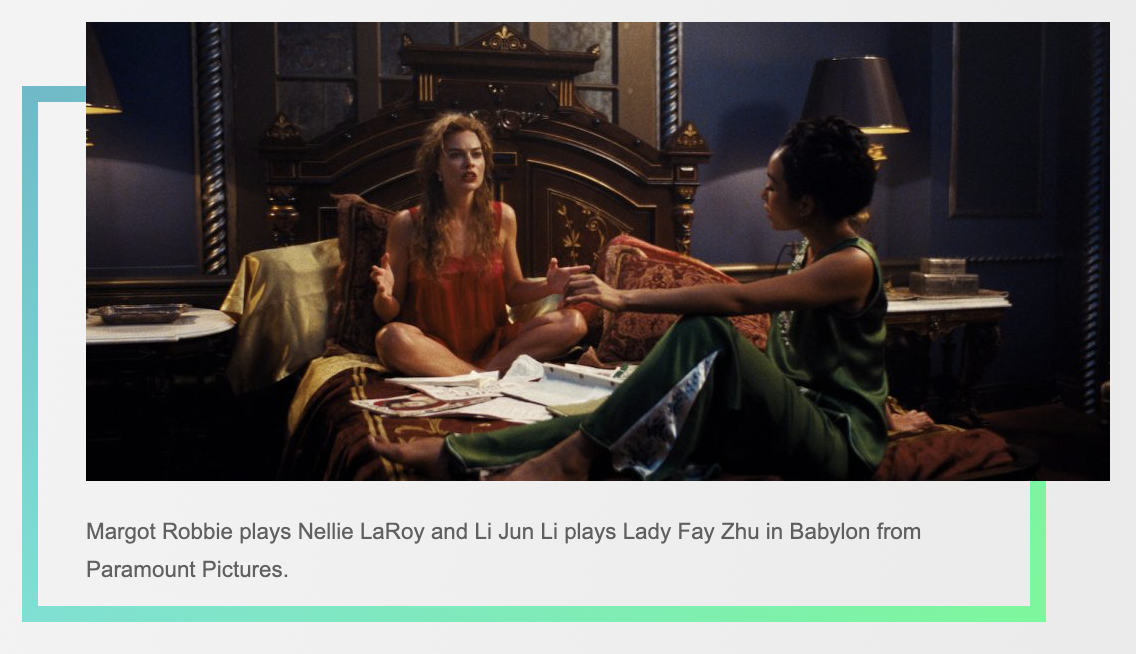

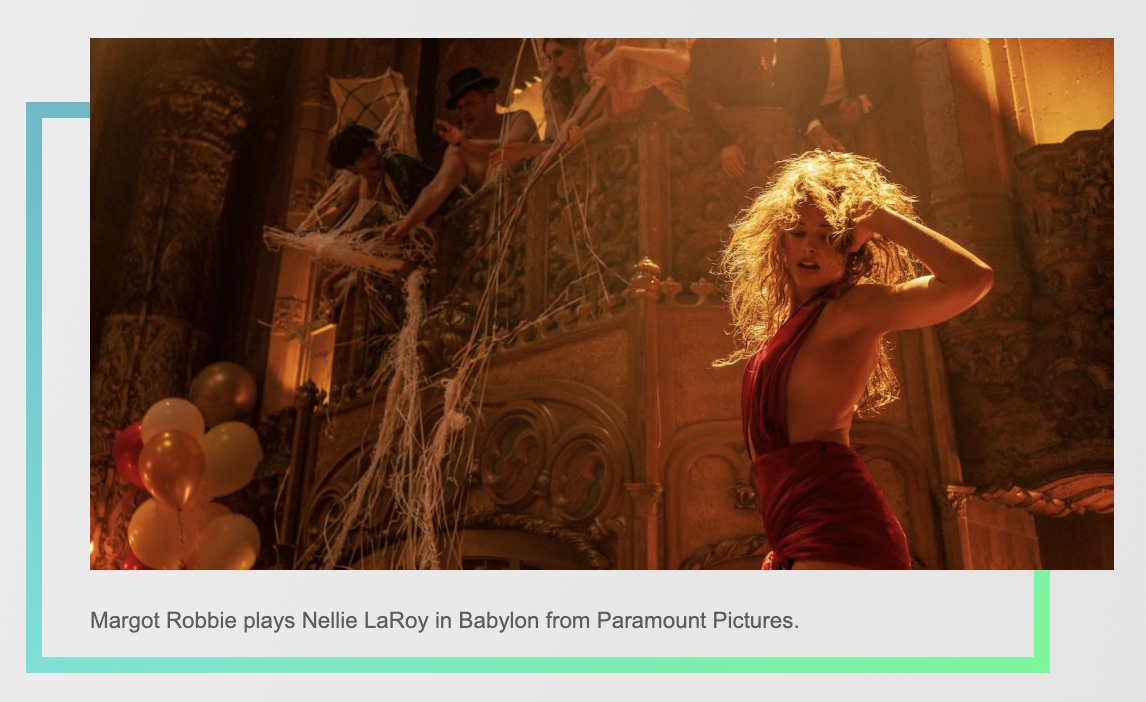

And that ballroom itself, where the crowd of coked-up revelers watches Margot Robbie do her crazy dance?

We found that at the Ace Theatre in downtown L.A. built in the 1920s by Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks to showcase their films. It’s just dripping with Hollywood history and detail. The theater offered us the [sense of] compression that Damien wanted, to make the crowd feel shoulder to shoulder and wild. We had to transform this theater space into a ballroom, so my team built custom gothic doors to plug the entrances, we put in parquet flooring, and we built the bandstand. A lot of work went into restructuring this location to make it feel like an interior home.

Before working on Babylon, you re-created various chapters of Southern California history for Blonde and Licorice Pizza. As somebody who grew up in Los Angeles, how have these film projects impacted the way you see this city?

The city’s always changing and transforming. In Babylon, we depicted Chinatown, which was replaced four years later by Union Station, and then you have the formation of the studio system that allowed for the development of all these apartments in Blonde that you see Marilyn Monroe living in as she moved around the city. With Licorice Pizza, it’s about the development of the suburbs in the San Fernando Valley. In L.A., you have old movie palaces and amazing Googie-style diners being torn down for something new, but we don’t really know our own history that well. With Babylon, it was an honor to get to preserve some of that history on film.

This article was first published on The Credits