Hugh Hart

Hugh Hart has covered movies, television and design for the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Wired and Fast Company. Formerly a Chicago musician, he now lives in Los Angeles with his dog-rescuing wife Marla and their Afghan Hound.

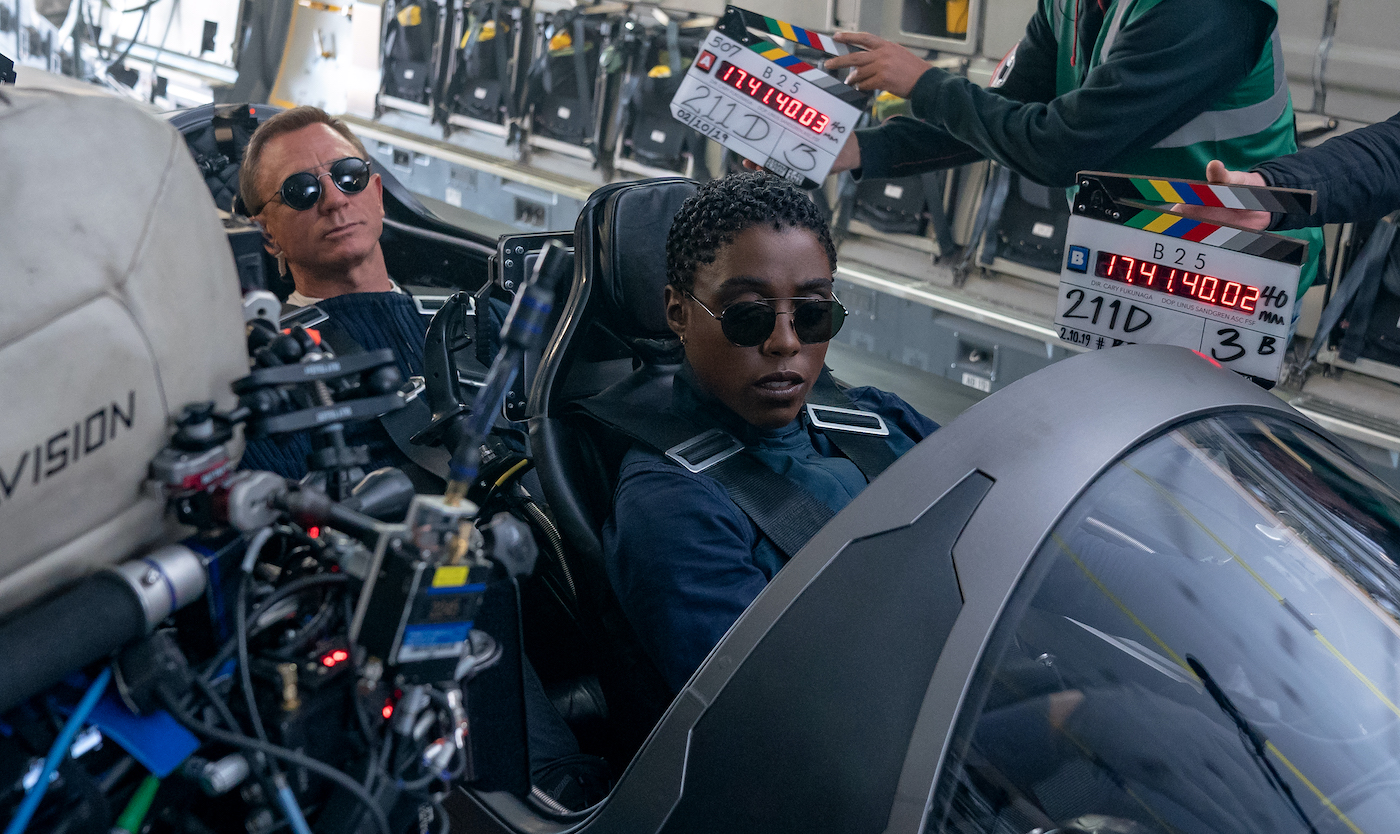

In No Time to Die, Daniel Craig gets two hours and 43 minutes to show James Bond fans what they’ll be missing once he exits his five-movie run as the world’s most enduring British spy. Following Craig’s every step, car chase, and explosion along the way is Swedish DP Linus Sandgren. “It was important in this film to make sure that we bookend Daniel Craig’s chapter of Bond in an exciting way,” says Sandgren. Acclaimed for his Oscar-winning cinematography on La La Land as well as American Hustle and NASA space epic First Man, Sandgren joined director/co-writer Cary Fukunaga, cast and crew on a globe-hopping seven-month production filmed in Norway, Italy, Jamacia, London, Scotland, and the North Atlantic Faroe Islands.

Co-starring Rami Malek, Léa Seydoux and Ralph Fiennes, and Lashana Lynch as the first Black female 007, No Time to Die offers plenty of spectacle, augmented in some theaters as the first Bond movie to be filmed partially in IMAX. But Sandgren takes just as much pleasure in capturing smaller moments. Speaking from his home in Los Angeles, Sandgren offers his take on the cinematic virtues of location-hopping, the beauty of handheld camera work, and the pleasures of capturing Daniel Craig’s emotional range in all his Bondian glory.

In the best Bond tradition, No Time to Die hops all over the place. How did all these locations impact the cinematography?

In a global adventure like this, locations give you a great opportunity to travel and put the plot into whatever location fits the story, and the cinematography is crucial for the emotions to come through. That’s how I like to think about it. I don’t like to think of cinematography so much technically. It’s about emotions and feelings. Thrills, joy, laughter, humor, you always try to relate the imagery to these emotions.

Another Jame Bond tradition: the big set piece at the beginning usually features 007 in some spectacular action sequence. Here, we open on a mother and daughter in Norway with Bond nowhere in sight. It’s quite a contrast in scenery when Bond then makes his appearance.

We wanted to go from this horrific incident in a cold, icy location where we make you really feel the isolation through the cinematography. And then we cut to [coastal Italian village] Matera, which is hot, sunny, and the complete opposite of the snow. Matera’s this very romantic setting, which we captured by shooting at sunset, through dusk to twilight. Cary was very eager to have the story jump each time to a new place.

Next day it’s the same location but a totally different vibe. How did you achieve that?

The morning starts out very romantic as well, but suddenly changes into the worst location you could be in if you’re being chased because you’re going to hit your head really hard against these hard rocky walls in this location that just a minute ago seemed so romantic. For the chase, the light becomes very bright and harsh scary. We also go from sweeping, picturesque visuals to much more handheld [camera work] which gives us this raw, brutal imagery for the action.

Bond’s first mission targets a Cuban nightclub (filmed in Jamaica). What kind of atmosphere did you want to render through your cinematography?

The exotic streets of Cuba we decided to shoot in twilight. Then later at night, they travel out to sea in the boat and we shoot that dark blue, not black night, so you can still have a little bit of light in the sky. Even when something’s monochromatic, it’s always more interesting when there’s color. And a big part of the film’s visual [style] is that we intended it to be colorful.

You shot on actual film stock, which is pretty rare these days. How did that choice affect the way you shaped your color palette?

Nothing was forced on the color during post-production. By capturing everything on film stock, the lighting color temperatures we worked with made each location feel distinct and also helped set the mood we were trying to create for that scene.

So what you shot is what you got, as opposed to digital, where filmmakers often modify the color in post-production?

Making No Time to Die, my intention is that whatever we shoot in-camera, on set, should come back the next day and that is what the film should look like ever after. I’m disappointed if it does not look the way I lit it and captured it in the camera. But sure, when I shoot digital, like on La La Land for example, you use look-up tables to create a distinct look and then you proof-process the footage to get a smoother, softer contrast. But in this case, we did our tests, shot on film, and processed our film stock in the normal way.

No Time to Die features a lot of epic wide shots. What format did you use?

We shot anamorphic 35 mm as the base for our story, and then we filmed certain sequences with IMAX cameras. If you see these scenes in an Imax theater, the image opens up below and above your head as a way of giving the audience an additional experience of immersive-ness.

You’ve previously worked with intense actors like Ryan Gosling in La La Land and Christian Bale in American Hustle. Viewed through your lens, what is it that makes Daniel Craig so appealing as a screen presence in this, his final Bond film?

He has such a range. Daniel can be charming and witty but he also has the ability to kill a lot of bad guys. And then he can also be very soft or emotionally sensitive. The thing Daniel brings to the Bond franchise is this depth of emotion, where he’s able to express loss and grief and love. As a cinematographer, I’m always thinking “What is this scene about?” Sometimes it can get so emotional that you almost want to be a little bit behind the actor in certain scenes because you want to be respectful and watch him in a more effective way than if you have him looking right into the camera.

With five Bond movies now under his belt, Daniel Craig at this point probably serves as an all-around creative partner as well as an actor.

Definitely. He’s very much a filmmaker, involved in discussions on set. And as an actor, he’s very professional. Daniel knows where the cameras are, he knows where to face himself to catch the light in his eye to look more heroic.

Yet he never seems self-conscious. When Daniel Craig shifts into fight mode, do you approach the camera work differently from his more intimate scenes?

When Daniel’s in danger, we oftentimes work with handheld cameras. He picks something up. Cut. There’s a gun. Cut. He’s smart, swift, and very effective.

No Time To Die is in theatres on November 8.

This article was originally published on The Credits.