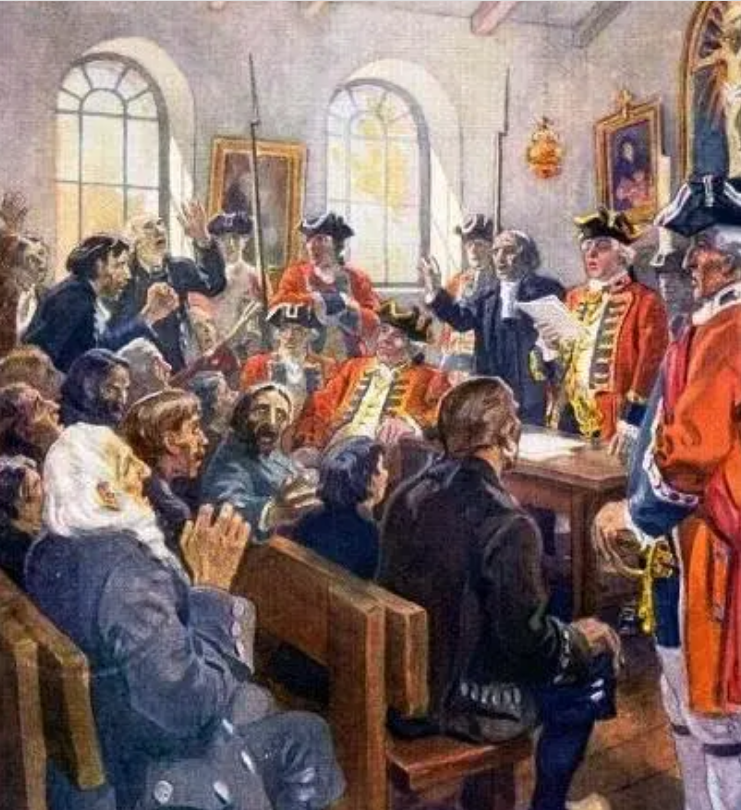

Painting by C.W. Jeffreys, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Resurrecting this 1950s-era Joe Friday (played by Jack Webb) quote from the TV series Dragnet may date me but it is a classic. The request seems so simple. Just the facts, and nothing but the facts. Facts are integral to interpretation of copyright law because “the facts” cannot be copyright protected. As almost everyone knows–but it bears repeating–copyright does not protect ideas or facts, only original expressions of ideas (and expressions that may be based on facts). Thus, Van Gogh’s painting of a vase of flowers could be copyright protected, but anyone can paint their own version of flowers in a vase. Winston Churchill wrote several copyrighted volumes about his interpretation of what happened in the Second World War, but the circumstances and facts of that conflict are open to anyone to write about. I was thinking about history and facts this summer when my wife and I visited one of Canada’s National Historic Sites, Grand Pré in Nova Scotia, site of the “Acadian Expulsion”. (known in French as Le Grand Dérangement).

The “facts” are probably generally if imprecisely known to many, especially in Canada and the US. The reasons why it happened, also part of the narrative, are less definitive. Here are the essential facts. In 1755, the British governor of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence, ordered the removal of some 6,000 Acadians settled in the areas of the Fundy marshes, close to present day Wolfville, NS. It was a brutal event; the settlers’ houses were torched, livestock killed, families often separated. The Acadians were widely scattered, with many being settled in the New England colonies and later in Britain and France. They were not, contrary to popular belief, deported to Louisiana, but many of those who eventually ended up in France were recruited by the Kingdom of Spain to settle in Louisiana, at that time under Spanish control. Spain wanted reliable Catholic settlers for colonization purposes. This is the foundation of the Cajun (Cadian) people of Louisiana. Some members of the Acadian diaspora eventually found their way back to what are now Canada’s Maritime provinces. Their return was permitted after 1764 following the defeat of France in North America and the fall of Québec. They settled largely on the north shore of what is now New Brunswick since New England Planters from the Thirteen Colonies had taken up much of their original lands. This part of New Brunswick has become an Acadian stronghold, and a strong sense of Acadian nationality and pride has developed over the years. Today it is common to see Acadian flags flying, and the Acadian star adorning houses in areas where Acadians reside.

The resurgence of Acadian awareness and pride can, ironically, be traced to a 19th century American poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who in 1847 published the opus “Evangeline”. This was a poetic work of fiction based loosely on the Acadian Expulsion (or Upheaval, as it is sometimes called), centred around a deported Acadian heroine, Evangeline, who for years engaged in a fruitless search for her deported betrothed, Gabriel, only to find him in Pennsylvania on his deathbed many years later, afflicted by the plague. As a work of fiction, Longfellow’s work was of course copyrighted. The poem was his expression of what had happened to the Acadians. Given its date of publication, its copyright protection has long since lapsed, and it has been in the public domain for many years. But behind Longfellow’s epic poem, and a few other early works written about the Acadians, (offering various interpretations and perspectives), there are “the facts” explaining what actually happened, and why. But what did actually happen? What are the bare facts?

You would think it would be relatively straightforward to recount the factual story but recall this all happened 250 years ago. The most public display of “the facts” is at the Grand Pré exhibition hall, run by Parks Canada. And this is where it becomes somewhat difficult to get to the unvarnished truth, “just the facts”.

The site is a place of pilgrimage for Acadians, part of their national story. People come to visit the Evangeline Chapel built in 1924 when the site was first established as a memorial. But one must not forget the Mic’maw people who populated the area before the Acadians arrived, and after they left. They are still around, still active and very vocal. And then there are the New England settlers who were brought in to take over the lands of the Acadians and establish a “loyal”, non-Catholic presence. Many of the current residents of rural areas of Nova Scotia are direct descendants of what is known as the New England Plantation. In addition, there is the interpretation of the positions of the then British and French governments, and the role they played, and the responsibility they bore. The display panels at the Grand Pré site, in English and French, do a good job of trying to manage the interpretation of the facts in a way that meets contemporary needs, or at least will offend the least possible number of people!

While we were at Grand Pré there was an historical re-enactment. An actor dressed up as an Acadian told us about the shock of the expulsion, being separated from her children, and so on but then in an aside made it very plain that the New England settlers who arrived a year or two after the Acadians had been forcibly removed were not to blame for the expulsion. In fact, when it came to explaining the reasons for the expulsion, there were several different options to choose from in the interactive displays. It was clear that the Acadians were expelled for refusing to take the oath of allegiance to Britain, which was the governing power in Nova Scotia since the area had been ceded to them by the French in 1713 in the Treaty of Utrecht. That treaty still left the French in possession of Québec and what today is called Cape Breton Island, where they established the fortress of Louisbourg. Those French fortresses were perceived to pose a threat to the English settlements further south, including Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Between the French and the English settlements lay Acadia, governed by Britain but populated largely by French speaking settlers whose loyalty was, at best, dubious. Some had actively aided French expeditions sent south to penetrate the area, although others had remained neutral. Was it unreasonable for the British to be concerned about what in later years would be called a “Fifth Column” in their midst? Was it unreasonable to pressure the Acadians to pledge loyalty to Britain, which some did but most resisted? I guess it depends on your point of view and the judgement of history.

But what about the Acadians? Why didn’t they accept their fate and realize they had been abandoned by France? Perhaps they had hopes that the outcome of Utrecht would be eventually reversed (since Britain and France seemed to go to war with each other every 10 years or so). Or was it because they were concerned their Catholic faith would be in jeopardy, given that Britain would not guarantee this? Another theory has it that the Acadians, who had a close but not completely satisfactory relationship with the powerful Mik’maw, were afraid that they would be subject to attack if the Mik’maw thought the Acadians were accommodating the British. There were no doubt many reasons for their refusal.

The Mik’maw also play a role. They were originally dispossessed by the Acadians, but had been converted to Catholicism, and thus there was a certain bond between the two groups. Apparently intermarriage was not infrequent. The Mik’maw fiercely resisted the British for a number of years to the point that Governor Edward Cornwallis offered a bounty for Mik’maw scalps. This has put Cornwallis, who founded Halifax and who is considered the father of Nova Scotia, in bad odour in today’s climate of reconciliation. (Edward was the uncle of Charles Cornwallis who surrendered British forces to George Washington in 1783). Cornwallis issued his proclamation after the Mik’maw had attacked and killed settlers. Today that would be called defending your land. Who is right? What are the “facts”?

You won’t find “just the facts” in Longfellow’s poem, or even definitively in the Parks Canada panels at Grand Pré describing the events of the day. As I noted, great effort has been made to present all views and, presumably, to let visitors decide for themselves as to what led to the Expulsion. This interpretation of the “facts” by Parks Canada historians, who have to answer to all segments of public opinion, could certainly be copyrighted as one expression of what happened. I am not aware that copyright has been asserted although it is possible that the interpretive panels and content are under Crown copyright. That would be appropriate as the “balanced and blended” interpretation of the reasons for what happened to the Acadians between 1755-1764, and why, is still only one version. Joe Friday didn’t realize what a complicated question he was asking when he uttered that famous expression, “Just the facts, ma’am”.