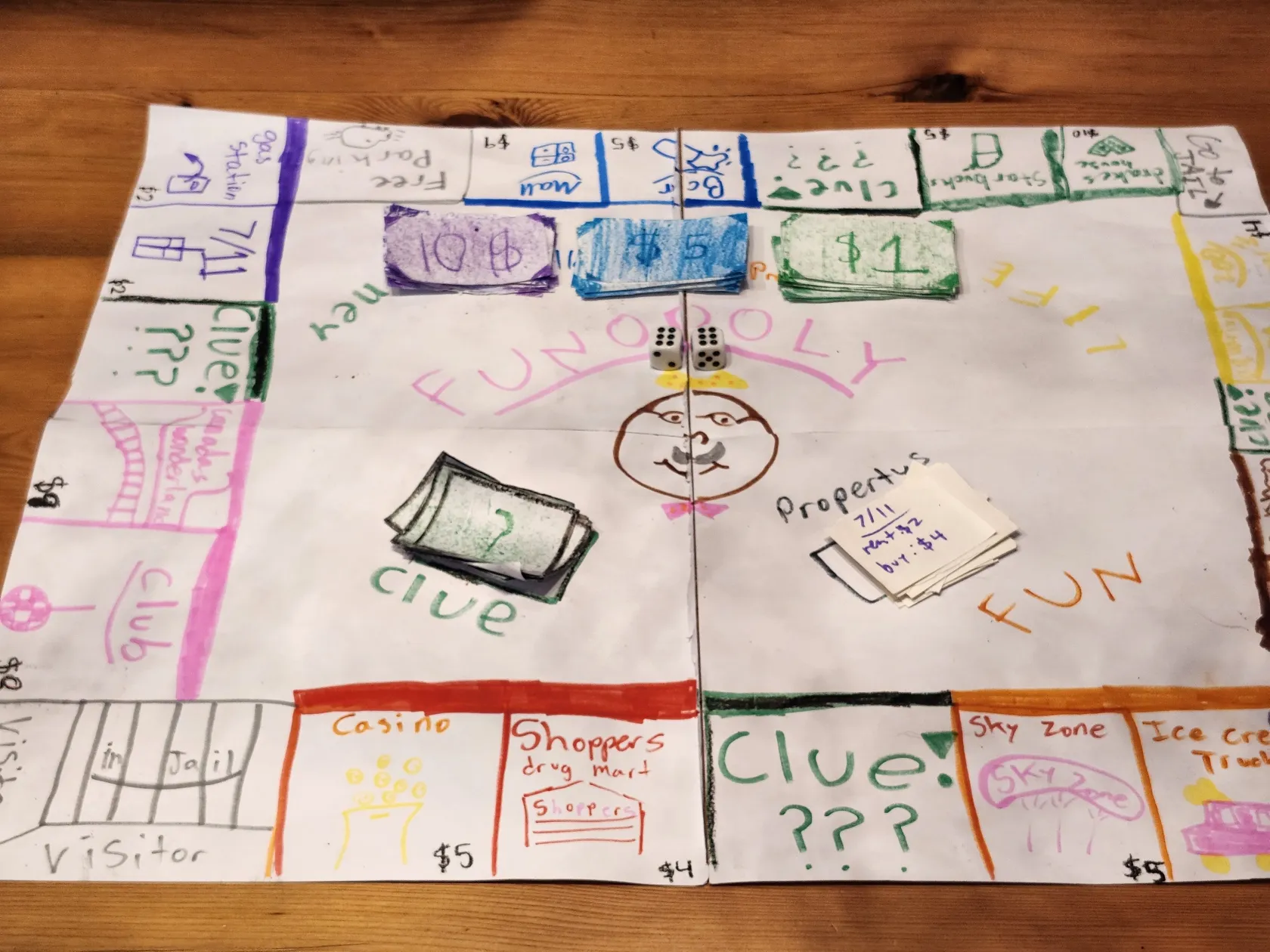

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about Copyright in Cottage Country, and how those wet afternoons are often occupied with cards or board games, like Scrabble, Clue or Cranium, all of which (the board games, that is) are copyrighted (and trademarked). What I neglected to mention is that, in addition to these well-known pastimes, during our recent stay at the cottage we also played several games of “Funopoly”. Now, I realize you may not have heard of this game, despite its uncanny resemblance to another much more famous, commercially available game that has been around for decades. I was introduced to it when I noticed a plain cardboard box lying on the dining table. “What’s that?”, I asked. “Oh, it’s a game I brought up to play at the cottage”, said my very creative 11 year old granddaughter, Stella. “I made it”.

Although Funopoly has a number of similarities with its famous counterpart, including the concept of buying property and paying “rent” if you land on a square, it is a different game. There are no houses or hotels to buy. You won’t find any Park Places or Boardwalks. Rather you might land on Shoppers’ Drug Mart, or Skyzone Trampolines or Canada’s Wonderland, all places in Toronto. The most expensive property on the Board, valued at something like $50, is the home of prominent rapper Drake, (actually valued at around $100 million) . But even though there are Canadian, British, Australian (and many other) geographically modified editions of Monopoly, this is not simply a Toronto version of that game. (The original US version was based on street names from Atlantic City, NJ. The British edition, also dating to the 1930s, used London street names. A Canadian edition debuted in the 1970s using street names drawn from cities across the country, from St. John’s, Nfld to Victoria, BC).

Funopoly doesn’t have street names. Another difference is the money, handmade and coloured $1 (green), $5 (blue) and $10 (purple) notes. There is a limited supply of each, and there seems to be equal numbers of each denomination. As in Monopoly, you get a reward (in this case, $1) for passing Go. But the properties are relatively expensive in proportion to the amount of money you have in hand. As a result, the first time we played I faced early bankruptcy as I had the misfortune to play last and landed on a couple of properties that had already been purchased. The “rent” was crushing and the paltry replenishment when my token (a coloured Qtip) passed Go didn’t cut it. Stella modified the game the next time we played, with players being rewarded with $10 when they passed Go. In this case, the bank soon went bankrupt as all the money was in the hands of the players. Funopoly is clearly a work in progress and is still being fine-tuned–but is a lot of fun. There are also no railroads or utilities, but there is a casino, a club and an ice cream truck. You seem to end up in jail on a regular basis, but get out just as quickly, something like the “catch and release” policies followed by Canadian courts for frequent offenders. Don’t look for Funopoly on Amazon. There is only one extant version in the whole wide world, and it is definitely not for sale. And I have had the privilege of playing it (and losing).

Knowing that I write a copyright blog, Stella asked if she could copyright Funopoly. I explained to her that if it is an original work in a concrete form (i.e. fixation), then copyright is automatically conferred. However, if she wanted a nice certificate to prove that it was copyrighted, that could be arranged. For $50, I could get her a vellum-like certificate from the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO) proclaiming her copyright in Funopoly. She would not even have to send in a photo of the game, because CIPO does not want or keep any copies of the works they are registering. (Many years ago, the Copyright Office required deposit of a copy of the work to be registered, but no longer). Nor does CIPO verify whether the work conflicts with another registered work. All they do is register a description of the work—and send you a nice certificate of copyright, as I demonstrated last year when I registered some AI created artwork and poetry, (Canadian Copyright Registration for my 100 Percent AI-Generated Work). Maybe we will register Funopoly. The certificate would be a nice birthday present for her.

Canadian copyright registration certificate or not, we must still ask the question as to whether this is an original work. Does it infringe on the copyrights or other forms of intellectual property (IP) protection of others? It turns out there has been a long history of IP disputes over Monopoly. The game was first published under the Monopoly name by Parker Bros in 1935 but there were earlier versions variously called “The Landlord’s Game”, “Finance”, or “Auction”. The game’s invention has been credited to Charles Darrow but there is strong evidence that rather than inventing the game, his genius was in marketing it, the original concept being created 30 years earlier by Lizzie Magie who had patented The Landlord’s Game in 1903. While the design and artwork (tokens, the board itself, other unique elements such as game-specific cards) around a board game can be protected by copyright, the actual rules of the game can be patented. And of course, the name (such as Monopoly or Scrabble) can be trademarked.

Each of these forms of IP protection has different characteristics. A patent has to be examined and accepted, and there is a limited period of protection, about two decades. Copyright is also time-limited, albeit of much longer duration. Trademark protection can be continuous, providing the mark stays in use and is renewed as required, normally every ten years. There was a notorious dispute in the 1980s over a game called “Anti-Monopoly”, that involved challenges to the trademark. In the end, Parker Bros. retained its trademark on Monopoly and acquired the trademark Anti-Monopoly, then proceeded to license it to the creator of the Anti-Monopoly game.

However, while many of the aspects of a board game can be protected by IP laws, some cannot. This is where the idea/expression dichotomy comes into play, meaning you cannot copyright an idea, only the expression of an idea. Thus, anyone can make a game that involves the buying and selling of properties and sending a person to jail for a variety of infractions. Anyone can make a game that involves moving a token around a board according to the role of a die or dice. But the rules of a game and its artwork and design can certainly be protected by both patent and copyright, and if a game that was sold commercially was substantially similar to a copyrighted work, with only a few details changed, that could be a factor in finding infringement.

Substantial similarity is another one of those complicated copyright issues. Simply put, you cannot simply change a few words in a published work, or presumably just a few features in a copyrighted game, and claim it is a new work. But substantial similarity is an elastic concept; even different judicial circuits in the US interpret it differently, according to this article from lawfirm DLA Piper. For my part, I am convinced that Funopoly is substantially different from Monopoly. What other game in the world uses a coloured Qtip as a token?

Nonetheless, as I am always quick to point out, I am not a lawyer and any interpretation of copyright laws that you find in this blog does not constitute legal advice. Instead, I try to go to reputable sources to buttress my opinions. I can find no better source than the American Bar Association, which outlined all you need to know when it comes to IP and board games. Will Hasbro, (now the owner of Monopoly) come after Stella to shut down Funopoly? Somehow, I doubt it. In fact, according to the ABA there are several “opoly” named games registered with the USPTO, a precedent that should help. In the meantime, we can pursue a Canadian copyright registration and obtain a pretty but not very useful certificate to hang on the wall.

Funopoly is not going to make Stella’s fortune. The real inventor of the property game concept, Lizzie Magie, got only $500 and no royalties in the mid-1930s when Parker Bros bought up rights to related games from her to protect its monopoly on Monopoly. Stella for her part won’t earn a cent from Funopoly, but that is not the point. Playing Funopoly with her on a rainy day at the cottage—even though I went bankrupt–was a priceless experience, and was the true reward.

This article was first published on Hugh Stephens Blog