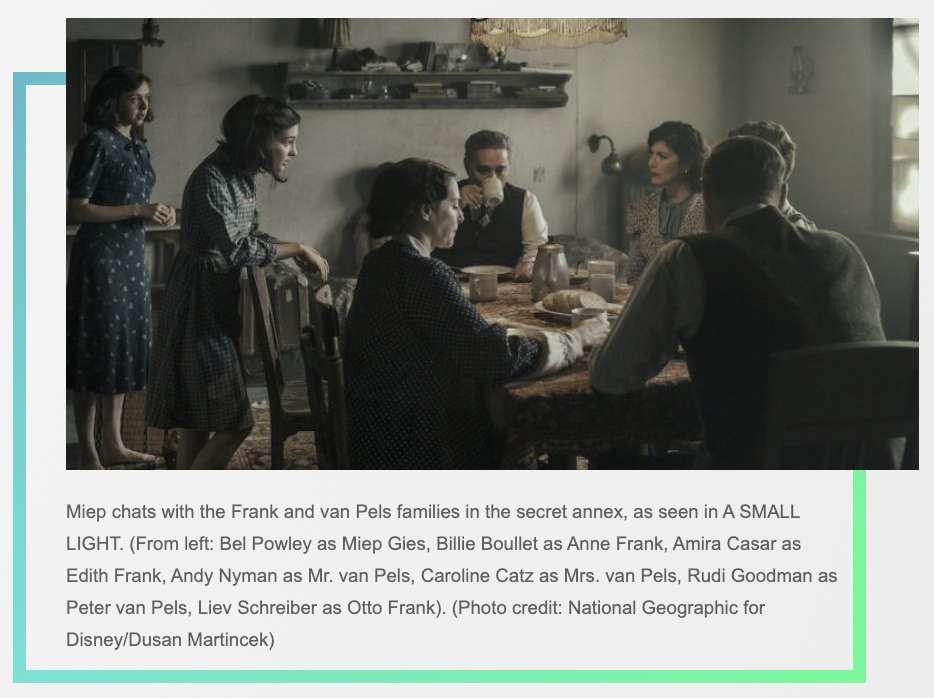

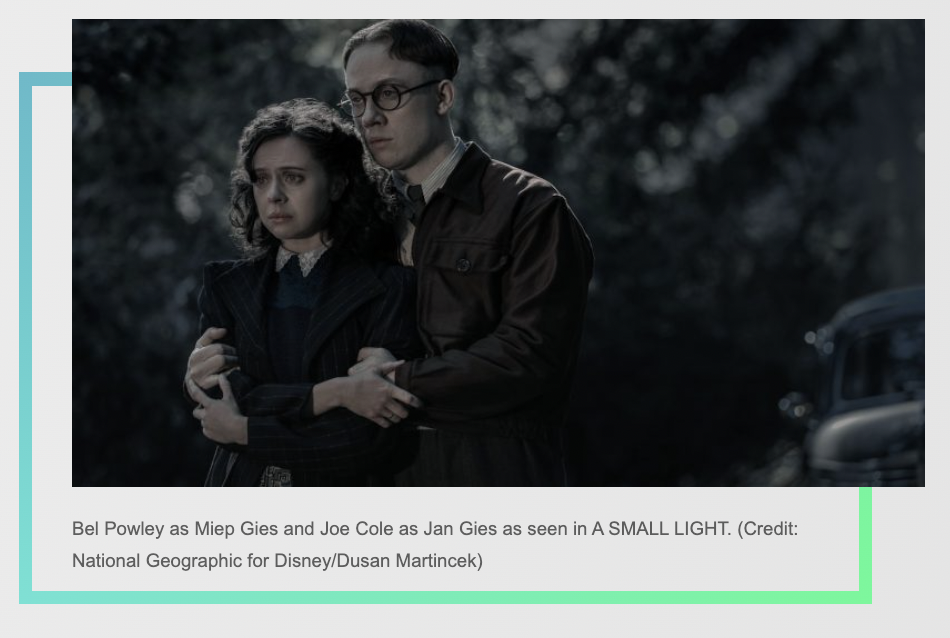

With Holocaust Remembrance Day having just passed and with antisemitism on the rise around the world, the release of National Geographic’s new eight-part miniseries A Small Light couldn’t come at a more apt time. The series is based on the true story of Miep and Jan Gies, who risked everything to hide Otto Frank and his family from the Nazis during World War II. Miep Gies discovered and kept Anne Frank’s famous diary safe until after the war.

A Small Light follows Miep (Bel Powley) from the time she worked for Otto Frank (Liev Schreiber) through the two years she and her husband Jan (Joe Cole) took care of Frank and his family, working to keep them safe in the secret annex of Otto Frank’s company headquarters.

Joining the project’s creators, husband and wife team Tony Phelan and Joan Rater, is co-executive producer and director Susanna Fogel (The Flight Attendant, Cat Person)., who helmed three episodes of the series. Speaking to The Credits, Fogel discusses her collaboration with the department heads in order to create a warm, cinematic aesthetic and the importance of giving the story a vibrancy and authenticity that does justice to the heroes and heroines represented.

The visual aesthetic of A Small Light is very cinematic, with its golden brown tones, use of light, and shot composition. What was your collaboration like with production designer Marc Homes to bring everything together?

I had worked with Marc before, and he’s an incredibly meticulous person. He had been an art director for many years for Ridley Scott, and so he was used to working on these really large-scale productions and getting into the very fine details of what sets need to look like, right down to the building materials and the level of distress of a very specific type of wood. The idea for the show all around, in terms of the aesthetic, was to create a canvas that feels true to the period and then let the people live and breathe, like real people, within this world. It was basically setting the stage in a way that feels like its period appropriate, but then injecting it with as much life as we could.

How did you approach creating the annex?

Marc did an exhaustive study of what the annex really looked like and built an incredible replica of it. It was a little bit different because it had to be suitable for cameras to go to different places, but it was pretty much exactly like the actual annex. We had him start with that accuracy, and then from there, we tried to figure out how to add color, life, texture, softness, humanity, and warmth onto that base layer so the show has all of that. A vibrant blanket or pillow or sweater can just really be the small light in the shot, too, so we were just conscious of always trying to have that.

And with your cinematographer Stuart Howell and costume designer Matthew Simonelli?

Stuart’s amazing. He had worked on The Crown, so he’d obviously shot these beautiful period pieces before. With him, again, we wanted this to feel as cinematic as possible and as epic as possible, to do justice to Miep’s story. At the same time, we were constantly working to add color and life to every aspect of the show. That was an aesthetic choice, too. With Matthew, it was the same thing. We talked about the characters having bright, colorful clothes because even though the world going on around them is falling apart, they’re not picking drab clothing; they’re picking the clothing they like to wear, so we wanted that to feel like it reflected their personalities too, and not just period.

Can you talk a bit about shooting the scene with Miep, Jan, and their friends jumping into the canal? Where was that shot?

We shot that in a town called Haarlem, just outside of Amsterdam. Those are the kinds of shots that we knew we couldn’t really recreate anywhere but Amsterdam.

That scene has a visual symmetry and a warmth of color that is representative of the show as a whole.

It was about combining the personal, lived-in feeling of the show with a well-composed, well-designed show, wanting it to feel really intentional but also wanting like there was spontaneity within these intentional shots. That scene encapsulates a lot of what the show is; the streets are really dark at that point, the war is on, and the lamps are out, and there are all these austerity measures throughout the city, but then there are these friends who are young, and they’re jumping into a canal and laughing. It’s all of it. It’s the joy, and also these little signifiers, that there’s still a really bleak situation going on at the same time. Filming that was great. We only got one take of them actually jumping in the canal, so we were lucky that it worked out.

The executive producers and co-showrunners are a married couple, with both Joan and Tony writing and Tony directing. It seems like their partnership must have been helpful in creating a believable and positive portrayal of Miep and Jan. What were your experiences around that?

I think we all brought our relationships, our relationship histories, and our friendships to the project. We all talked about that stuff, so even though they’re characters and we’re trying to engineer something that feels realistic, we’re all drawing from our own experiences, like, for example, what it feels like to be in a fight. One of my favorite scenes in the show is the fight in the pilot that Miep and Jan have about whether or not she should have told him she made this decision. They go back and forth between being mad and trying to reconcile and then getting mad again, and it just felt so spiky and relatable. When Joan and Tony were writing that, we talked a lot about that scene and letting it just be kind of a mess and letting it be a bit shaggy and long. People make circular arguments sometimes. In the end, the scene plays in a pretty linear way, but the footage that went into making that scene was more all over the place by design because we just wanted to capture the spontaneity there. We all just felt that electricity when we were shooting it. Like any show, if the people making it are forthcoming with their own personal issues, demons, and flaws, then the characters take on some of those layers and feel like they really come to life.

How did you, as director, bridge the gap of telling a story based on history while making it relevant and connected to what’s happening around us today?

I think the connections between what this show is about and what’s happening today are just baked into the fact that history tends to be cyclical, and we’re dealing with a lot of these issues of nationalism and invasions of countries and occupations. All of these things happen over and over around the world, and they’ve been escalating ever since we started working on this show. If it resonates and feels personal that there’s a global situation, and people are just trying to figure out how to deal with each other, deal with their relationships, and deal with growing up. There’s the world that’s getting increasingly scary, and that feels like a pretty timeless feeling. With antisemitism on the rise, it’s just become more and more timely in the process. We just had to make the show deliver and feel warm and relatable and human enough that people didn’t feel like it was a stodgy period piece, and they could watch it and connect to it and then hopefully extrapolate about their own lives now.

This article was first published on The Credits